Mount Vernon: A Letter to the Children of America

New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1859.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

Introduction

In 1853, Mount Vernon on the Potomac River, the beloved home of George Washington, was falling into ruin. Its then owner, John Augustine Washington, Jr., could not afford to maintain it. A South Carolina socialite, Louise Dalton Bird Cunningham, traveling up the Potomac by steamer, noted and was horrified by the neglect and approaching destruction of Mount Vernon, and wrote to her daughter, Ann Pamela Cunningham, “If the men of America have seen fit to allow the home of its most respected hero to go to ruin, why can’t the women of America band together to save it?” Miss Cunningham organized the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, and called on American women everywhere to support the project. By 1858 the Association had accumulated enough money to buy Mount Vernon, and it took possession in 1860. Since then, continuing to raise necessary funds from the public, it has owned and maintained Mount Vernon as an American shrine.

The Mission Statement of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association of the Union, as it is now known, reads: “Mount Vernon is owned and maintained in trust for the people of the United States by the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, a private, non-profit organization founded in 1853. Visitors can see 20 structures and 50 acres of gardens as they existed in 1799. The estate also includes a museum, the tombs of George and Martha Washington, Washington’s greenhouse, an outdoor exhibit devoted to American agriculture as practiced by Washington, the nation’s most important memorial to the accomplishments of 18ᵗʰ-century slaves, and a collection which features numerous decorative and domestic artifacts. In 1999 Mount Vernon welcomed over 1,100,000 visitors.” The annual budget exceeds $12,000,000. For further details see the Association’s website.

Mount Vernon: A Letter to the Children of Americawas Susan Fenimore Cooper’s contribution to the fund raising effort, written in the year that Mount Vernon became the property of the Association. On July 12, 1858, Susan wrote to one of her sisters, expressing her pleasure at becoming involved with the Mount Vernon project. (See, Lisa West Norwood, “Domesticating Revolutionary Sentiment in Susan Fenimore Cooper’s Mount Vernon: A Letter to the Children of America,” a paper given at the 2001 Cooper Conference in Oneonta, NY.) Otherwise little seems to be known of the publishing history or subsequent use of this small book.

Most of Mount Vernon’s 70 small pages are devoted to a brief survey of George Washington’s life and career, concentrating on the Revolutionary War. Addressed to the “Children of America,” who are often referred to as “my children,” and “my dear friends,” Mount Vernonis intended to remind school children of what they have already learned in school, and to point out the moral, Christian, and political lessons to be learned from Washington’s exemplary career. Except for praising Washington’s love of his rural home and its round of farming activities, Susan concentrates almost exclusively on his public life. His family, and personalities of the Revolution and of his Presidency, are mentioned only in passing — no mention is made of African-Americans or his ownership of slaves. The frequent refusal of the American colonies, or of the Continental Congress, to give timely or sufficient support to Washington and his army is repeatedly denounced, though in general terms.

Nevertheless, though in a sometimes patronizing tone, Susan Fenimore Cooper — as in her other writings — often has cogent things to say about American history, political ethics, and culture. Mount Vernonis more likely to be of interest to students interested in Susan Fenimore Cooper’s life and outlook, and to adult-child relations in the mid-19ᵗʰ century, than to students of George Washington or even of Mount Vernon itself.

Except for the cover, and a title page reference to “the author of Rural Hours,” Mount Vernonnowhere mentions Susan’s name. Nor is there specific mention of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association — the property is described as in the guardianship of “the women of America.” And, while the “children of America” to whom the volume is addressed are invited to make small financial contributions to the cause (“whatever you may be enabled to give, be it a bright dime, or clean copper. ... “), the book provides no advice on how, where, or to whom such contributions can be made. This suggests that it was intended as a handout at the site. Though the book is comparatively hard to find, it has never been reprinted. In this transcription, no corrections have been made to the original — a few errors and/or unlikely readings are marked by “sic“. Page numbers from the original are indicated in {brackets}.

Cover of Susan Fenimore Cooper’s Mount Vernon.

{pages [1-2]} are blank.

{pages [3-4, 5-6]}

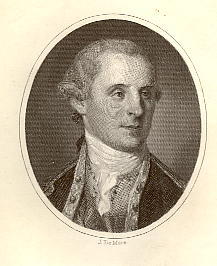

J. de Mare, WASHINGTON AT THE AGE OF TWENTY-FIVE.

{[6]}

Mount Vernon: A Letter to the Children of America

By The Author Of “Rural Hours,” Etc., Etc.

New York: D. Appleton And Company, 346 & 348 Broadway.

M.DCCC.LIX.

{[7]}

ENTERED, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1859, by D. APPLETON & CO. In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York.

{[8]}

Publisher’s Note.

THE readers of this little volume are indebted to the courtesy of Mr. George P. Putnam, publisher of Irving’s Life of Washington, for the two interesting illustrations which embellish it. The medallion likeness of “Washington at Twenty-five” is now first engraved from the veritable miniature presented by General Washington to his niece.

NEW YORK, December15, 1858.

{[9]}

MOUNT VERNON.

DEAR CHILDREN:

You have all been taught from your cradles to honor the name of George Washington. Many of you already know that Mount Vernon was his home, where he lived and died. Far away, in the good State of Virginia, an old, gray, stone house, with tall piazza, and peaked roof, and overlooking cupola, stands on an elevated bank, which is beautifully shaded by many different trees, while the broad river Potomac flows grandly below — this is Mount Vernon. Good men love their homes. General Washington loved Mount Vernon very dearly. He loved those gray walls for the sake of the elder brother who had built them — Mr. Lawrence Washington, who, in boyhood, had been kind as a {10} father to him. He loved the great woods, with their noble timber, and all the wild creatures sheltered there; he loved the broad farms with their rich crops, their fresh springs, the patient flocks, and the kindly cattle feeding on the sweet grass of the field. Our Heavenly Father has given many gracious blessings to a country home; and all these were enjoyed by General Washington, with a wisely thankful heart.

It is more than a hundred years since George Washington first lived at Mount Vernon. He went there a youth — a noble youth of fifteen, sound in body, ardent in temper, generous at heart, purely upright in word and in deed. Already, at that early day, he was fitting himself with care for the great work of life — by study, by forming healthy habits of body and of mind, by good thought and worthy action.

Pause awhile, dear children; turn eye and heart towards that quiet country home, on the banks of the Potomac. Remember all you have read, all that has been told to you, of the great man whose noble head was so {11} long sheltered beneath that roof. Remember his honorable youth; see him first crossing the threshold of Mount Vernon, with his surveying instruments, when a growing lad of sixteen; see him bravely making his way on foot, on horseback, through forests, over mountain and marsh, exposed to all winds and weathers, ever diligent, ever trustworthy, ever faithful to the task of the hour. See him when still a beardless lad, drawing maps, and making surveys, so correct in all their parts, that to this day practised lawyers turn to them in cases of doubt and dispute.

See him watching, in sickness, by the side of the kind brother who loved him so truly; see him intrusted with the guardianship of the little fatherless child, and the large property of that brother — he who was then himself but a youth under age. Well and honorably indeed must his first years of manhood have been passed, to justify such a trust!

Observe him during the long struggle, and the many difficulties of the Old French War, as we call it in our histories. Behold him, at nineteen, one of those intrusted with the duty {12} of preparing his native province for war. Call to mind all his toil, all his perils, when, a few months later, he travelled through the wilderness at mid-winter, bearing letters from the governor of Virginia to the French commander, on the shores of Lake Erie. You remember that long and perilous journey, with all its hourly dangers from the deep snows, the angry rivers, the cunning wiles of the enemy, the treachery of the savage hovering about his path, more fiercely cruel than the beasts of prey. You remember well that false traitor, the Indian guide, who offered to lead him through the wilderness, and then, suddenly turning from his side, raised his gun, took murderous aim, and fired at the unsuspecting young officer! You remember the humanity of Major Washington, who disarmed the vile wretch, but gave him his life. And the raft on the wild waters of the troubled Alleghany [sic] — you have not forgotten that daring launch, with the long fireless night on the desolate island. You know already how faithfully the papers intrusted to his care were guarded amid a thousand dangers, and, after more than {13} two months of wintry peril in the wilderness, were safely delivered into the hands to which they were addressed.

Behold him once more leaving the quiet walls of Mount Vernon, and hastening, with early spring, at the head of his little troop of Virginians, to take post as the advance-guard of the province, breaking, with toilsome struggles, a road through the wilds of Western Virginia, along the passes of “Savage Mountain,” through those gloomy woods called the “Shades of Death.” Then came the skirmish at the Great Meadows, where the blood shed was the first drawn in a long and famous war — a war gradually extending from the mountain-passes of Virginia, and the wooded plains of Ohio, to famous fields of the Old World, to the banks of the Elbe and the Danube, where all the great powers of Europe were marching their armies to and fro. You know already by heart, my children, the course of George Washington through that war. You have followed in your histories the boastful march of General Braddock; you have noted the modest wisdom, the gallant bravery, the {14} generous humanity, of the young Virginian aid [sic]. So often have we read the narrative, that we seem almost to have beheld him with our own eyes, riding about that fatal field of Fort Duquesne, seeking to rally the flying troops, exposed to many deaths, horses shot under him, bullets passing through his clothing, his brother-officers falling one after another, and he left alone, his tall figure and fine horse a mark to the trained aim of the French soldier, and to the quick-eyed savage in his lair. * We, the women and children of the country, seem still to tremble, these hundred years later, at the dangers which threatened {15} that noble head. And you have read of the after-trials of the same war, darker perhaps to his ardent spirit than in the eager years of youth, than the fatal day at Fort Duquesne — trials of endurance under neglect, abuse and opposition — trials which, by the will of Providence, were moulding his character for difficulties still more severe, through which, at a later period, he was nobly to steer his own course and that of his country.

And then, when Fort Duquesne had at length fallen, when Canada had been conquered, and his native province was freed from peril, there came a period of honorable repose. Colonel Washington married. Mount Vernon became a happy house. My children, it is those we love — father and mother, husband and wife, brother and sister, son and daughter — it is these near and dear ones, sharing our joys and sorrows, with us at our daily meal, our daily prayer, these whose love goes with us along the whole path of life, and still watches over the grave — it is these best, most worthy, most enduring affections of our nature, which give, as it were, heart and soul {16} to the Christian home. George Washington was a man whose affections were true, pure, strong. The home of his boyhood now became dearer to him than ever, for the sake of the wife and children who shared its blessings with him.

There are men, my young friends, capable of great and honorable exertion when aroused by some urgent need, acting bravely and zealously in hours of danger, but sinking into weakness and selfish indulgence in hours of repose. Those were peaceful days to Colonel Washington. But the hours were not idled away. He well knew the great value of time worthily spent. The plantation of Mount Vernon was large, stretching for miles along the bank of the Potomac. It contained different farms, watered by brooks and rivulets, with much woodland also. The woods were left wholly wild, with large droves of swine feeding on the fallen acorns and beech-nuts. The farms were thoroughly worked. George Washington was a wise, industrious, thrifty farmer; he was not a man to be content with meagre returns from the soil; he spared no {17} pains to bring the very best crops from his fields. Once in a while a ship would sail up the Potomac, anchor in the river, and receive the choice produce of the plantation. The tobacco, good as that once smoked by Raleigh in the presence of Queen Bess, was sent to London. The return voyages brought him many necessaries of life, and many little matters which to-day you and I might find at the nearest counter in our own neighborhood. Colonel Washington wrote to London, for pins, for Mrs. Washington’s toilet, and for a doll, a doll for the little daughter of the house; “a fashionably dressed baby” it was to be! The flour from the fields of Mount Vernon was sent in other ships to the West India Islands, and there, my children, the name of George Washington became known in the markets, not as that of a gallant soldier, not as that of a wise statesman, but as the name of an upright man, an honest farmer, faultless in good faith. The barrels marked with that name were not opened for examination; the dealers were confident that the quality of the {18} flour within was precisely such as it was represented to be; it needed no inspection.

It was during those quiet years, my children, that a little church arose in the neighborhood of Mount Vernon, the church at Pohick, planned, and in a good measure built, by Colonel Washington. Every Sunday, as a rule, the gates of Mount Vernon opened to Colonel Washington and his family, on their way to the house of God. He was not one of those who, calling themselves Christians, yet neglect the public worship of the Lord God of heaven and earth.

It would not be easy, dear children, to imagine a more happy, a more honorably peaceful way of life, than that led at Mount Vernon during those quiet years; the active usefulness, the manly exercises without — the generous hospitalities, the neighborly charities, the happy family circle within — these gave Colonel Washington what his heart most enjoyed. But, my children, all these pleasures were now to be deliberately sacrificed; they were all to be nobly given up. Much as he loved that happy home, his {19} love of country was still stronger. His sense of honor, of duty, his reverence for truth and justice, were much too great to allow him to sit idle by the hearthstone of Mount Vernon when the highest interests of his country were at stake.

You know already that the war of the Revolution, which separated America from England, was brought on by the injustice of the English government. As we sow, so shall we reap, whether nations or individuals. Injustice, whether public or private, is doomed in the end, under one form or another, to work out its own punishment. The English government insisted on exercising in the colonies powers to which they had no just right. The people of the colonies remonstrated; they sought redress by peaceable means. They long clung to the mother country hopeful of justice and reconciliation; but, when all peaceful measures had failed — when troops were sent among them to compel obedience to laws plainly unconstitutional and tyrannical — then, at length, they were themselves {20} driven to take up arms in defence of their cherished rights.

The memorable war began between thirteen feeble colonies and their mother country, one of the richest and most powerful nations then on the earth. Small would have been the hope of these colonies if they had depended on the numbers of their troops, on the strength of their fortresses, on the size of their fleets. Regular armies they had none. Their fortresses were few and small, and chiefly in the hands of the enemy. With a sea-board coast stretching a thousand miles along the Atlantic, they had not one regularly armed vessel to represent a navy — to defend their hundred ports. But, my young friends, the hearts of the people were brave. For leaders they had wise and upright men. And the moral strength of their cause was to them like an impregnable citadel.

You already know who became the great leader of the American people in the struggle which then began. There was no man on the continent who felt a more generous indignation at the wrongs inflicted on his country{21}men, than George Washington, then in his peaceful home at Mount Vernon. With a devotion purely unselfish, he stood ready to give up life, and ease, and property, to the service of his country in her hour of utmost need. An American army was already gathering on the heights of Boston. An American Congress met at Philadelphia. Ere many days had passed, George Washington was unanimously appointed, by the Congress of the Colonies, Commander in-Chief of their troops. His skill as an officer, his position, his talents, his superior character, were declared such as “would unite the cordial exertions of all the colonies better than any other person in the Union.” Mark that word Union, my young friends, now first used on a most solemn public occasion — a word carrying with it a principle of wise statesmanship, of generous sympathies, of prudent conciliation — a principle which has been, more than any other, the life and soul of our common country, which has, under Providence, made of a dozen scattered provinces one great and powerful nation, which has bound up in one {22} common weal the hearts of millions of men, making brothers and comrades of those who, without it, must one day have become bitter rivals and deadly foes. And how happily was the word now uttered in this its very earliest use, connected with the name of George Washington — connected with the name of the man who throughout his whole course proved how deeply he felt the full force of its meaning — who labored so faithfully to uphold the just and wise and generous principles it involves.

The choice of Congress was unanimous. The gravely weighty charge was accepted with that unfeigned modesty, that noble humility, which entered so thoroughly into this great man’s nature. “There is something charming to me in the conduct of Washington, a gentleman of one of the first fortunes on the continent, leaving his delicious retirement, his family and friends, sacrificing his ease, and hazarding all in the cause of his country. His motives are noble, and disinterested.” Such were the words of John Adams.

{23} Then followed the daring siege of Boston. It was a siege begun with the utmost boldness, and carried on with a resolution, an unyielding fortitude under difficulties, still more remarkable. On the 3d of July, 1775, General Washington took formal command of the army — an army most uncouth to the eye of a soldier — a besieging army of husbandmen, without tents, without stores, ragged and half-clad, scarcely half-armed, and with little ammunition. But beneath that scanty clothing beat the hearts of brave men; the spirit of injured freemen lighted up those sharp features. The character of an army has ever been of far more importance than its weapons. Those rude countrymen had already compelled the brilliant English troops at Lexington to retreat. They had all but won the field of Bunker Hill from the experienced English general, commanding at Boston. During the first months they kept their ground bravely in spite of every obstacle. But these undisciplined yeomen, brave as men could be in the field, at length became weary of the camp. As the siege was prolonged their patience {24} failed. Discontent, murmuring were there, as the time of enlistment drew to a close; many left the camp, and turned their faces homeward. It needed a wiser courage than theirs, spirits more enduring, to complete the work so bravely begun. At one moment it seemed as if General Washington with his officers might be left alone on those heights — like fabled champions of old — beleaguering the British army in Boston! The American forces were melting away — varying with every waning moon — ebbing and flowing like the tides in the harbor below, but with far more of caprice and uncertainty in their movement, than that of the waves of the sea. But, in the midst of dangers, and trials, and difficulties far beyond what your young minds can now comprehend, the fortitude of General Washington remained unwavering. He prudently concealed his weakness. He patiently labored to enlist a new army — he planned — he wrote — he watched with unwearied fidelity. Men, cannon, powder, clothing, were sought far and near. In the very face of the enemy, the army was built up anew. No ad{26}vantage was lost. The American intrenchments were pushed nearer and nearer to the besieged town. At length the hour came — the city could no longer be held by the enemy; with the dawn of day, March the 3d, 1776, the bay of Boston was crowded with English shipping, getting under way; the British army hurried on board, and the fleet sailed out to sea. The victory was won. Boston was free. By noon General Putnam — that brave old man — had marched into the city; the young flag of the country was seen floating freshly over the town, in the bleak March breezes.

New York was threatened. General Washington hastened there. An attack was expected. It came ere long. A great fleet of one hundred and thirty sail appeared at the mouth of the Hudson, and was soon at anchor in the bay. An army of 30,000 men was on board. Their white tents arose on Staten Island — and, ere long, a large British force landed on Long Island, A battle was fought. The Americans opposed the enemy with great gallantry; but they had failed to {26} guard one important point — they were surrounded, and thrown into confusion. General Washington was in New York, preparing for an attack on the city; he hurried over the river, but only in time to see his defeated troops driven from their ground, and retreating toward Brooklyn. Happily for them, night was at hand. The fighting ceased. The Americans had lost two thousand men — the English commander believed a complete victory to be in his power — he felt sure of forcing the whole American army, now lying weary and defeated within sight and sound of his own troops, to surrender as prisoners of war. He lay dreaming in his tent. With early dawn he was aroused by strange tidings. The American army, to the very last man, had vanished — their camp, close at hand, was empty! It seemed incredible. Silently and swiftly, in the dead of night, shrouded in a heavy fog, the army had been withdrawn by General Washington, embarked in boats hastily brought together, and safely ferried across the river to New York. A more sudden and {27} and [sic] skilful retreat is scarcely to be found in the records of history.

But, my children, that celebrated movement, after the defeat on Long Island, was only the first step in a long course of deliberate retreat, now rendered necessary by the weakness of the American army, and the increasing strength of the British forces. New York could no longer be held. It was necessary to abandon the city. Slowly and painfully, amid many trials and vexations, General Washington withdrew his army to the northward. Wherever it was possible, there he paused; and his troops, skilful as ever with the spade, threw up intrenchments with surprising quickness of hand and eye. In October, amid the colored autumnal groves of Westchester, was fought the battle of White Plains, where the Americans yielded the ground, but without being defeated. Rapidly, during the dark hours of a frosty night, while the camp-fires of both armies lighted up the shadowy hill sides, our countrymen raised new redoubts, built up of maize stalks, and their shaggy roots matted with earth. By skilful work, and rapid move{28}ments, General Washington succeeded, in securing a position too strong for attack. The English general lay idle awhile in his camp, and then marched away, moving westward. Fort Washington on the Hudson was his object. This fortress protected the northern country against the English forces in New York. It was a post of great importance, but had not the strength to repulse alone an enemy of the force of General Howe. General Washington had wished to withdraw the troops. There was delay, and some indecision. A strong English army appeared, with a summons to surrender. They were very gallantly opposed. General Washington, then in New Jersey, became painfully anxious; on learning that the fort was besieged, he mounted his horse, rode rapidly to Fort Lee, on the Jersey shore, and threw himself into a boat, to cross the river; but he met General Greene returning with hopeful reports from the garrison. Stationing himself on the heights of the palisades, immediately opposite, the Commander-in-Chief now watched with the utmost anxiety the fate of his brave troops. But they had undertak{29}en a task beyond their strength; ere long the Commander-in-Chief had the bitter mortification of seeing the gallant defenders of the fort compelled to surrender. The American flag was lowered — nearly one-third of the army were taken prisoners, besides stores and ammunition of the greatest importance. Two thousand eight hundred men of the American troops were disarmed, and marched off at midnight to New York, prisoners of war. Sad was the fate of many of these, at a later day, in the wretched prisons where they were confined by the enemy, like evil-doers.

General Washington’s army was now but little more than two thousand men, chiefly encamped at Hackensack, in New Jersey. An English force, six thousand strong, suddenly crossed the river, to surprise them. General Washington was on the alert. Rapidly as possible he was compelled to retreat to save the small remnant of the American army; tents, baggage, stores, provisions, cannons — all were abandoned. At their utmost speed the troops move toward the bridge over the {30} Hackensack — they reach it — cross the river, and are safe for the day.

And then followed months of painful wanderings on the part of the enfeebled American army — as usual suffering for want of clothing, arms, and food, — “ragged tatterdemalions,” as the British officers contemptuously called them. Steadily and wisely General Washington led the forced retreat — now retiring at a slow, deliberate pace, now pausing; then again moving with the utmost rapidity, pressed by more urgent need — ever watchful, ever on the alert to seize the first opening for favorable action. He was compelled to cross the Passaic. The enemy pursued him closely. He reached Trenton, and crossed the broad Delaware. In hot pursuit the English army followed to the banks of the stream. They sought to cross. Boats could not be found — these had all been removed by General Washington’s orders. They hovered awhile on the shore, then scattered themselves over the adjoining country. That small American army was once more safe, for the moment. Time and again, my children, during the {31} course of that memorable war, were the slender American forces struggling for the freedom of the country, befriended, as it were, by the noble rivers of the land. The ample waters, flowing broad and deep, formed natural barriers against the invader.

But most gloomy were the prospects of the American army, now gathered on the western bank of the Delaware. The future lay dark, and seemingly hopeless, before them. Stout hearts began to fail. There was secret murmuring — there was underhand plotting — curses were at work — slander was heard. The character of General Washington was assailed. There were many now very ready to blame the Commander-in-Chief — was he always to retreat? Suddenly news flew over the country of a very brilliant action — an action wholly unexpected. Boldly recrossing the Delaware, on a cold and stormy winter’s night — Christmas-Eve of 1776 — at the head of his half-clad troops, General Washington had surprised, defeated, and taken prisoners a large body of the enemy’s Hessian troops, at Trenton. Then, moving gallantly onward, he had fol{32}lowed up his first success, in spite of urgent needs of men and money — and turning upon the enemy, defeated him at Princeton, drove him, in his turn, step by step, over the sandy roads of New Jersey, in full retreat. He closed the campaign by securing a favorable encampment for the winter among the heights of Morristown.

But, my young friends, we are wandering too far. Time would fail us, were we to linger at every striking event of that memorable war, in which General Washington stands prominent in the foreground. You may find the record of these events already printed on many a page; they are already written, it is to be hoped, on your own young hearts, beyond the power of forgetfulness. A rapid glance is all we may now allow ourselves. The gloomy months of the year 1776 relieved by the daring victory at Trenton; the march through Philadelphia the following season, the ragged troops wearing sprigs of evergreen in their hats as the best attempt at uniform their scanty clothing would allow; the defeat on the Brandywine, where the {33} gallant and loyal Lafayette first fought by the side of Washington; the loss of Philadelphia; the daring attack at Germantown; a victory won — then vanishing as it were in the fog and smoke of the field: of all these you have read. Then we come to the wretched winter at Valley Forge — the frosty roads marked with the blood of the bare-footed soldiers; the narrow huts of logs, without food, without clothing, without blankets to keep the life-blood of the men from freezing in their veins; nay, without straw for the sick to die on! And darker still, let us not forget the cunning plotting, the undeserved blame, the cowardly abuse; which in those months of gloom were aimed at the noble head of Washington. My children, the generous spirit is best known in the hour of trial. Undaunted, true to himself and to duty, devoted with all his powers to the good of his country, the character of General Washington never appeared more truly great than during those darkest months of his life — the winter at Valley Forge.

Then comes the French alliance — the {34} English leaving Philadelphia, General Washington again in pursuit of their retreating army through the Jerseys; the battle of Monmouth, so nearly lost, so bravely won; the return of Sir Henry Clinton to New York; the hopes, the anxieties, the disappointments of General Washington regarding the French fleet, and the winter encampment at Middlebrook.

The winter of 1779 was marked as usual with grave cares and severe trials to the Commander-in-Chief. Little sympathy had his generous nature with the petty jealousies, the narrow selfishness, which now began to show themselves but too plainly among the inferior political men of the day. The best men of the country, the men uniting ability with high moral character, were no longer in Congress. Well did he, the noblest among them all, feel the great truth, that when such men — the upright, the loyal, the unselfish — are content to leave the public work of the country in unworthy hands, more or less of public risk and public disgrace is inevitable.

With the next year, 1780, we have Gen{35}eral Washington on the Hudson, with his troops. And that most daring attack on Stony Point follows — a work so boldly planned by the Commander-in-Chief, thoroughly prepared, and most gallantly achieved by General Wayne, “Mark Antony” of the army — a strong fort, garrisoned by six hundred men, surprised and stormed at midnight by two hundred men! It was indeed a very gallant exploit — one of the most brilliant feats on record in the annals of war.

The winter of 1780, so terribly cold, is again marked by the sufferings of the American army, in their winter quarters at Morristown. As before, these brave men were left by the careless public officers without clothing, without bread, without meat, without money, in their narrow huts. Perchance they might have starved but for the kindly sympathy of the people of New Jersey, who brought them supplies out of good-will. How many leaves of the history of the Revolution are marked with the bitter necessities of the army — with the wearing trials and anxieties of their chief, for the lack of that aid from the government {36} without which we should have supposed they must have been almost utterly powerless! There were times when the difficulties appeared all but overwhelming. There was a childish littleness of calculation, a narrowness of views in the proceedings of Congress connected with the army, quite disgraceful; and when it is considered that the fate of the nation was at stake, such a course becomes culpable in the extreme. To a man of the singular discretion, forethought, and soundness of judgment of the Commander-in-Chief, such mismanagement must have been especially trying. Private affairs managed in the same way, must have brought utter ruin on any man. Happily the resources of nations are greater. When endangered by mismanagement they are often enabled to rally from what appears the brink of ruin. With republics this is especially the case. The broad principles of general justice which make up their constitution, carry life farther and deeper into their system than into that of other nations; they can bear with safety greater shocks, so long at least as the moral principles by which they exist are pre{37}served with any degree of fidelity. They often appear strangely weak, while yet they have at the heart life-giving fountains of strength which enable them to rally and to act in time of need, with a vigor perhaps wholly unlooked for, and far beyond that of their adversary — startling the world by their proofs of power. Thus it was in the war of the Revolution. The great moral principles of simple justice, for which the people and their leaders were honestly contending, buoyed them up amid innumerable stormy perils.

Spring found General Washington at West Point, anxious, as he had been for a long time, to attack New York; but he was not strong enough to undertake a step so important, unsupported by the allied forces of France. A French fleet was hourly expected at Newport. Meanwhile Sir Henry Clinton had sailed southward, reduced Charleston, after a very gallant defence of that city by General Lincoln and his troops, and had again returned northward, leaving Lord Cornwallis in Carolina. There was now a seeming quiet in the English {38} camp. Sir Henry Clinton appeared idle. Ah, little did General Washington know the danger which threatened him from that quarter; little was he aware of the work now plotting under the eye of Sir Henry Clinton! Letters were passing up and down the Hudson, of which he knew nothing — letters from his own camp at West Point to the British head-quarters; one day borne stealthily in boats gliding under the shores — at another carried by land along the highways, passing from one treacherous hand to another. A traitor stood by the side of the Commander-in-Chief, breaking bread with him at the same board, sharing his secret counsels — a traitor far more guilty than the wild savage who had once fired upon him in the wilderness of Ohio. The French fleet arrived. Unsuspicious of evil, General Washington, anxious to prepare for the intended attack on New York, left West Point for Hartford, to meet the commander of the allied forces just arrived. At the very hour when the Commander-in-Chief of the American army was sitting at the council-board in Hartford, in consultation with the Count de Rocham{39}beau, treachery was busily at work on the banks of the Hudson. The traitorous plan was completed. All was ready. At midnight, of a beautiful starlight night, the 21ˢᵗ of September, an English officer landed from a boat at a solitary spot in Haverstraw Bay. It was at the foot of Long Clove Mountain, which threw its starlight shadows over the wild spot. There, concealed in a thicket, shrinking from the dim face of night, as it were, like the guilty creature he was, stood an American general, come there with the vile purpose of selling on that spot, and at that hour, his comrades, his chief, his country, and his honor, for a few paltry pounds of gold. Wretched man that he was — you know his name already, my young friends, but too well. The guilty tale has been often told to you. Let us have done with it. But, as we pass up and down that grand river to-day, with a speed scarcely leaving time for thought, let us still send up to Heaven an aspiration of thankfulness for the protection vouchsafed in that evil hour to our country, her army, and her great leader.

The plot was discovered. Benedict Ar{40}nold escaped, safe in body, blasted in name forever. The luckless young English officer, André, was executed, sternly, but justly, in accordance with well-established military law.

General Washington’s mind was scarcely relieved from this critical danger, ere his attention was again engrossed by the state of the army. Difficulties, as of old, want of men, and of means, beset his path. Not a month, not a week, scarcely a day, of those long years was free from trials of this nature. Time and again, well-formed plans of the Commander-in-Chief and his generals were abandoned, for the lack of that aid they had every just reason to demand. Many a victory, many a gallant exploit, my young friends, might have been added to the history of the Revolution, as it now stands on record, had the men and means pledged to the Commander-in-Chief been faithfully provided. But, as we look backward to-day, knowing that the great national battle was happily won at last, far higher than the renown of victory may we prize those grand lessons of wisdom, of prudence, of fortitude, of unwavering devotion to duty, of faith {41} in the power of truth and justice, as they are taught by the example of George Washington, in those hours of severe trial. The attack on New York was still the project which the Commander-in-Chief had most at heart, believing that one successful blow struck here by the united armies of America and France must insure an early peace. But, as usual, there was delay. The armies were not yet ready for action.

Meanwhile the brave States at the southward — the Carolinas and Virginia, had become the field of war. It was on that ground the great battle of the nation was now fought The American troops in that quarter, like their brethren at the North, were often wanting in almost every essential of war but gallant hearts and brave leaders. The names of Lincoln, Greene, Sumter, Marion, Washington, Morgan, and others, their comrades — how many daring exploits, under cloud or sunshine, do they recall to us! How often have we read the story of those bold attacks, skilful retreats — the rising of the rivers one after another — the Catawba, the Yadkin, the {42} Dan; one army pursuing the other in quick succession, with rapid changes, until suddenly and unexpectedly General Greene moves southward, and Lord Cornwallis, after a brief and anxious delay, fearing the loss of all he had hitherto won in Carolina, changes his direction also. And the two armies, which but a few days earlier were closely pursuing each other, one or the other in advance, according to the chances of war, were now seen flying far asunder, towards opposite points, each commander with an object of his own. Lord Cornwallis was eager to reach Virginia, to unite his own diminished forces with the British army already there. Little did he dream of the circumstances under which, ere many months had passed, he should again pass the bounds of that State!

For some time Arnold — the guilty Arnold — had been in command of the enemy’s forces in Virginia, ravaging the country with a heartlessness that proved plainly that with his allegiance he had also forgotten the spirit of humanity which has marked American warfare. The watchful eye of the Commander-in-{43}Chief, from his camp on the Hudson, took in the whole field of war. The movements of armies, to the utmost extent of the country, were often planned by him. He may have felt something of additional sympathy, as he saw now his native province laid waste by the enemy. A proof of the strength of his love of country, of his high sense of honor, is now given to the world, though at the moment known only to the man to whom his rebuke was addressed. Mount Vernon was threatened with fire by the enemy. Other country houses had been recently burned by the British troops, in Virginia. The agent, to save the house and the plantation from ruin, sent provisions to the enemy, and went himself on board their ship. The indignation of Gen. Washington, on learning this fact, was great indeed — he could not endure the thought that a person, representing him during his absence, should have taken a step so unworthy. Much as he loved Mount Vernon, greatly as he longed to return there, he could not endure the idea that safety should have been purchased by an unworthy act: “It would have {42} been a less painful circumstance to me, to have heard that in consequence of your noncompliance with their request they had burned my house, and laid my plantation in ruins.” Such was his private rebuke to his agent: strong language, but, like all language used by George Washington, the honest expression of his heart. He had long since deliberately declared himself ready to sacrifice life and property to the service of his country; he now stood ready at any hour to carry out that pledge to the utmost — to preserve, at every cost, pure integrity of word and deed.

General Washington was now encamped on the Hudson, among the Greenburg hills, about Dobb’s Ferry, anxiously awaiting the arrival of additional troops before moving upon New York. The attack on that city was fully prepared. The French army under General de Rochambeau was lying among the Greenburg hills, in close neighborhood, and in good fellowship with the American troops. The generals had gone over the ground; their plans were complete. They were only {45} awaiting the reinforcements expected by the American army. But the fresh troops came in very slowly, and in small numbers. General Washington was pained and mortified by these delays, at a moment of the highest importance. At length, however, towards the middle of August, preparations were more actively carried on. A large encampment was marked out in the Jerseys — to surround New York by all its approaches seemed the object; ovens were built, fuel was provided for baking the bread needed by a large force; pioneers were sent forward to break the roads leading towards New York, and prepare them for the passage of troops and artillery. At length, on the 19ᵗʰ of August, the army was paraded, with their faces towards New York. The order to march was given — but, to the amazement of the troops themselves, they were turned in the opposite direction from the British posts. They had expected to attack. They moved to the northward some miles, then crossed the Hudson. The French forces followed in the same direction. The camp already prepared in the Jerseys was supposed {46} to be their goal. But such were not the views of their leaders. They marched through the Jerseys without pausing, leaving New York in their rear. Now, at length, it became evident that Virginia was their object. Stirring events were taking place on that ground. Generals Lafayette and Wayne, by a series of skilful movements, had not only escaped from the pursuit of Lord Cornwallis, but, carrying out the suggestions of General Washington, had succeeded in throwing a military net-work about the British army, confining it within narrow bounds by a skilful distribution of the American forces. At the same moment, the expected French fleet was found to have changed its destination from New York to the Chesapeake — a fact which rendered it necessary to postpone the attempt on New York, while, on the other hand, it rendered the hope of capturing the British army in Virginia almost certain. This intelligence had caused the sudden movement of General Washington and Count de Rochambeau to the southward. Sir Henry Clinton was amazed when he learned the allied armies had already {47} reached the Delaware. They marched through Philadelphia; they passed over much the same ground as in 1777, but under very different circumstances. Lord Cornwallis, finding it impossible to withdraw his army, prepared to defend himself at Yorktown, strengthening the place to the utmost of his power.

On the 28ᵗʰ of September the allied American and French armies, twelve thousand strong, began their work as besiegers. The Commander-in-Chief, the Count de Rochambeau, Generals Lafayette, Wayne, Steuben, Lincoln, and many other distinguished soldiers of both armies, were on the ground. Governor Nelson, of Virginia, brought the militia of that State into the field, raising the funds for their expenses by pledging his own private property for the purpose. The besieging works were commenced, stretching before Yorktown in a semicircle nearly two miles in length. General Washington closely superintended the labors of the troops. He was frequently exposed to great danger; but, as usual, wholly forgetful of personal risks. His {48} generals, at times, remonstrated with him upon his want of caution.

The English army, now closely shut in on all sides, soon became distressed. They were compelled to kill their horses for want of forage. Parties were sent out to procure provisions; skirmishes took place. In one of these Col. Tarleton, with his famous legion, mounted on race-horses, had a sharp melée with M. de Lauzun, and his brilliant French hussars. On the 6ᵗʰ of October, in the depths of a dark night, Gen. Lincoln, with a body of French and American troops, opened a parallel — as it is called in the language of sieges — within six hundred yards of the enemy. It was nearly two miles in length. So silently, and so skilfully, was the work carried on, that the enemy was wholly unaware it was going on, until the morning light appeared. This work was soon completed. A terrible cannonade followed; General Washington firing the first gun. Gov. Nelson was consulted as to the point toward, which the cannonade should be directed, to do most effective work. A large house was quietly pointed out by him, {49} as the enemy’s head-quarters. It was his own. Of course it was destroyed. All the usual glaring terrors of a regular siege followed. On the 11ᵗʰ, a second line, within three hundred yards of the enemy, was opened by General Steuben. Two British redoubts seriously retarded the work. They were most gallantly stormed in the same night — the 14ᵗʰ — one by a party of Americans under General Lafayette, the other by a French force under M. de Viomeiul. The Americans, headed by Colonel Hamilton, rushed upon the redoubt without firing, without awaiting the usual military approaches — the fatal work was done at the point of the bayonet. The French, having a stronger garrison to oppose them, advanced more regularly, but with equal gallantry. Both parties were entirely successful. The loss of these redoubts threw Lord Cornwallis almost into despair. The British made a very spirited attack on two American batteries — but they were forced to retreat. Lord Cornwallis could not endure the idea of surrendering. He sought to escape — to force an opening to the southward. The daring at{50}tempt failed. Finding longer defence hopeless — at 10 o’clock on the morning of the 17ᵗʰ, a flag was sent to General Washington with proposals of surrender. Two days passed in the necessary consultations. On the 19ᵗʰ of October, Lord Cornwallis, and the British army under his command — some 7,000 in all — formally surrendered, with all due military observances, to General Washington, as Commander-in-Chief of the allied armies.

The great struggle was nearly over — closing, for General Washington, as it had begun, with a siege. But very different was the management of the siege of Yorktown, carried on with every regular military proceeding, from the protracted labors, the disheartening delays and hinderanccs of that remarkable siege of Boston, in which the Commander-in-Chief first made proof of all his personal powers, as an American general.

With the fall of Yorktown the English Government abandoned all hope. Ere long rumors of peace were heard. Still General Washington, ever watchful and provident, returned to his post on the Hudson, prepared {51} to continue hostilities should it be necessary. The troops were marched to Newburgh. The army under General Washington was not again called into the field. And yet its presence in the camp was never more necessary. Now that the attention of the troops was no longer fixed upon the enemy, now that peace was at hand, a peace purchased by their gallantry, they began to turn a sullen eye upon the internal affairs of the country. The conduct of Congress, and that of the State governments, with regard to all the interests of the troops — officers and men alike — had been strangely and culpably negligent. Even now, when the freedom of the country had been wrought out by their gallantry and fortitude, they were still but half fed! Long arrears of pay were due to them. The murmuring and discontent increased to an alarming degree. The real danger to the nation was, perhaps, greater at that moment than at any period during the Revolution. — A secret proposition was made to General Washington: Why should he not assume the supreme command of affairs, and with the aid of the army crown {52} himself King! A noble burst of indignation was the only reply of the Commander-in-Chief. Never, perhaps, was there a public man more free from the taint of petty personal ambition. Still the mutinous disposition of the army seemed to be gaining ground. The great degree of justice in their complaints increased the danger a thousand-fold. Disorder, violence and anarchy threatened the country — and like their sister republics at the southward, these States might have become a prey to successive military outbreaks, and military leaders. But the evil was wholly warded off, and the country saved from untold disorder and violence — the integrity, the wisdom and upright character of one man contributing, more, perhaps, than any other influence, to avert the imminent danger. Sharing, as he had done, all the trials and dangers of the army, feeling for the officers and the men with an interest almost fatherly in its warmth, by his calm wisdom, and generous example, he was enabled to control the stormy elements.

“Blessed are the peace-makers, for they shall be called the children of God.” If such {53} be the blessing of the man who in private life seeks to cherish the lovely spirit of peace, how much greater must be the merit of the Christian patriot, who, in seasons of discord, promotes by word and by deed that unspeakably great blessing — national peace! A close more worthy of the great military career of the Commander-in-Chief could scarcely be named.

And now, on the 19ᵗʰ of April, the eighth anniversary of the battle of Lexington, the close of the war with England was publicly proclaimed to the army.

It was still some months, however, ere General Washington was released from public cares. The breaking up of the army; the fatherly leave-taking from the soldiers; the solemn parting with his officers, marked by manly grief; the careful and patient settlement of business questions with the British officials; his frequent communications with Congress, with the State authorities; his simply dignified resignation of the supreme command at Annapolis — all these different duties delayed his homeward journey.

{54} But at length, on Christmas Eve, 1783, came the happy hour. Once more the gates of Mount Vernon opened to receive him; he was once more at rest within those honored walls. How simply true, that from early youth he seemed never to have left those walls, save on some worthy errand — ever, as he returned to their shelter, bearing with him, year after year, fresh claim upon the respect, the veneration, the gratitude of his country.

Very happily must the early spring of Virginia have opened to the great and good man. His mind was given once more to the peaceful cares and genial toils of the husbandman. Ere long, loving country life as of old, we find him keeping a diary of all the little events of interest. As the months went round, the days, marked so often in past years with the gloomy trial, the terrible battle, are now given to the peaceful work of the farm and the garden. Jan. the 10ᵗʰ — the period of the stormy winter campaign in the Jerseys, he now quietly notes that the thorn is still in full berry. Jan. the 20ᵗʰ — the anniversary of the bitter hardships of Valley Forge, the suffer{55}ings of his army, the plottings of his secret enemies in the Conway cabal — we now follow him into his pine groves, where he is happily busy clearing openings among the undergrowth. In February, the moment when, during a previous year, the threatening military outbreak was gathering to a head in the Highland camp, he is pleasantly engaged in transplanting ivy. In March, when the siege of Boston was drawing to a close, engrossing every faculty, he is setting out evergreens — the spruce which throws its dark shadows over many a hillside in our country. In April, the month of Lexington, he sets out willows and lilacs — he sows holly-berries for a hedge near the garden-gate, and on the lawn. He rides over his farms, choosing young trees, elms, ashes, maples, mulberries, for transplanting. He sows acorns and buck-eye, brought by himself from the banks of the Monongahela. Ho twines honeysuckles around the columns of his piazza — the ever-blooming scarlet honeysuckle which the little humming-bird loves so well.

The first months of peace, which follow a {56} long war, arc often perilous to a nation. The excitement of conflict is over, and there remains many a deep wound to be healed. But there were especial dangers connected with the first movements of a young nation like our own, with a form of government still untried. There was naturally much of evil passion, of prejudice, of folly, astir. “What, Gracious God! is man, that there should he such inconsistency and perfidiousness in his conduct?” was the heartfelt exclamation of General Washington, amid the discord and disorder which in 1786 were threatening the very life of the nation. You know already, my young friends, how by thoughtful prudence, plain justice, and a wise conciliation, the evils so much dreaded by every good man were warded off. A wisely framed Constitution for the nation was drawn up, and in 1788 happily ratified. “We may, with a kind of pious and grateful exultation, trace the finger of Providence through these dark and mysterious events * * ” again writes General Washington, “in all human probability laying a lasting foundation for tranquillity and happiness, when (57} we had but too much reason to fear that confusion and misery were coming rapidly upon us.”

A permanent government was now formed. It remained to choose a President. The eyes of the whole nation were again turned towards Mount Vernon. General Washington had not one secret wish for the honors of the high dignity. To General Lafayette he wrote that he had no desire “beyond that of living and dying, an honest man, on my own farm.” The election took place. From the very heart of the nation, George Washington was chosen President of the United States. Never was there a public choice more honorable to a people, or to the individual chosen. With noble humility, with virtuous resolution, with manly dignity, the weighty charge was accepted. Seldom indeed has a position of such high honor been assumed from motives so simply pure and disinterested.

On the morning of the 16ᵗʰ of April, General Washington again crossed the threshold of Mount Vernon, again sacrificing the peaceful life he loved, to high public duty. {58} Childhood may love its home, as the fledging [sic] bird loves the nest where it is fed; and fondled youth may love its home, as the young bird flutters joyously about the tree whence it first took wing. But as the shadows of life lengthen, home becomes far more dear. It is in maturer life, when a knowledge of the vanities of the world without has forced itself clearly upon the mind, that the family hearthstone of a virtuous house becomes to the wise man the dearest spot on earth. It is there that, next to Heaven, the heart centres. And when we behold a man clothed with years, and well-earned honors, the rich fruits of a lifetime of virtuous action, deliberately leaving his peaceful roof, to enter once more the toilsome path of public life — a path whose severe labors, whose weight of care, whose risks, whose empty returns, he already knows to the utmost — our hearts are deeply moved at the spectacle, with feelings of reverence and gratitude.

Four long years of weighty care and labor passed over. The work of the nation went on. Laws were enacted. Treaties were made. {59} An Indian war was carried on. Taxes were laid. Opposition awoke. Party spirit became active and violent. And amid the turmoil and uproar of political life, General Washington moved on his course, calm, firm, just, upright as ever. The period for another election came round. He was again unanimously elected President. The first term of his service had been chiefly occupied with the regulation of internal affairs. Meanwhile great revolutions were breaking out in Europe; their natural effects on America were soon felt. War was declared between Great Britain and France. The government of the United States, with General Washington at its head, wisely resolved to remain neutral. But party feeling ran high — its spirit was never more bitter, dividing the nation into rival adherents of England or of France; as though we were no longer the independent people we had so lately proclaimed ourselves to be. But where two powerful countries are at war, the position of a neutral people of less power, and in any manner connected with them, becomes full of difficulties. The United States suffered {60} in many ways by this state of things. England boldly impressed seamen from American ships, arrogantly insisting on a right to do so. France, with equal disregard of all national laws, openly interfered in the internal affairs of the Union. In the midst of these embarrassments, of the gravest character, the President earnestly sought to preserve national justice and national dignity. “I wish to establish an Americancharacter.” This impartial and independent course exposed him to much of the grossest abuse. Even his personal character was assailed — and by his own countrymen! Of so little true value may popular favor or popular abuse become. The truly great man must know how to rise far superior to either in the hour of need. “I prize as I ought the good opinion of my fellow-citizens; yet, if 1 know myself, I would not seek popularity at the expense of one social duty or moral virtue.” Such were his words. Such was his course.

At the close of the second term of his service, he announced to the country his resolution to withdraw into private life. It was on {61} that occasion, as you remember, that he wrote the Farewell Address, which, with Laws, and Constitutions, and Treaties, has a place in the archives of the nation. How much of undeniable truth, of pure wisdom, of sound judgment — how much of warm love of country, assuming in the venerable man a touching paternal character, is found in that paper. How earnestly he desires we might shun every peculiar danger of our position — with what fatherly foresight he warns us against the most threatening evils. Speaking of a free government, he plainly declares a very great truth: “Respect for its authority, compliance with its laws, acquiescence in its measures, are duties enjoined by the fundamental maxims of true liberty. The Constitution which at any time exists, until changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government, pre-supposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government.” How justly he valued true freedom, and how clearly he saw the {62} fact, that it can never exist on earth without the restraint of law and justice, duly observed: “It is indeed little else than a name, where the government is too feeble to withstand the enterprises of faction, to confine each member of society within the limits prescribed by the laws, and to maintain all in the secure and tranquil enjoyment of the rights of person and properly.” How well he describes party spirit, as often a small, but artful and encroaching, minority of the community. “It exists under different shapes in all governments * * but in those of a popular form it is seen in its greatest rankness. and is truly their worst enemy.” How plainly he urges the great truth, that there can be no sound, no lasting popular government, without a living spirit of virtue and religion in the hearts of the community. How carefully he teaches the importance of public honesty — the upright discharge of debt. How nobly he would impress upon the country the observance of good faith and justice towards all nations, “cultivating peace and harmony with all.”

While the nation were still reading this noble address, the venerable man was gladly preparing to lay aside his public honors, and thankfully turning his face again toward his own quiet roof.

It was a happy moment of the year for the aged patriot to enter his own gates. With returning spring, his stately person, now venerable with years, was again seen moving about his fields, directing the work of his laborers, passing along familiar paths, overshadowed by the trees he loved so well. His doors were once more thrown wide with the olden hospitality, generous in spirit, simple in form. His barns and storehouses were again opened to relieve the poor, as in previous years, when he wrote, during the trials of the siege of Boston: “Let the hospitality of the house with respect to the poor be kept up. Let no one go hungry away. If any of this kind of people should be in want of corn, supply their necessities, provided it does not encourage them to idleness.” He who in early youth, before he was yet of age, was the chosen guardian of the fatherless little girl, was now the friend {64} to whom more than one widow, more than one orphan flock, looked for aid, and guidance, and protection.

Ere long, public cares followed him again to his plantation. The difficulties with France were gradually becoming more grave. It became necessary to prepare for war. So long as General Washington lived, the people were unwilling to trust their armies to another chief. “In the event of an open rupture with France, the public voice will again call you to command the armies of your country,” writes General Hamilton. “We must have your name,” writes the President; “there will be more efficiency in it than in many an army.”

With deep regret General Washington again saw the toils of public life spreading before him. But true to duty as ever, unselfish in his noble old aged as in ardent youth, he declared himself reluctant to leave his retirement, yet ready to serve his country, if needed: ” The principle by which my conduct has been actuated through life would not suffer me, in any great emergency, to withhold any {65} services I could render, when required by my country.”

In July, 1798, the Secretary of War was sent by the President to wait on General Washington, at Mount Vernon, bearing with him the commission of Lieutenant-General, and Commander-in-Chief of the armies of the Republic. From that moment, the summer days were divided between the necessary preparations for the duty before him, and the lighter labors of the fields, which he ever loved so well. As ho rode over the hills, and through the woods, on the banks of the Potomac, his mind was filled with plans for the war which seemed so near. Yet, to his experienced eye, that cloud of war appeared more likely to pass away. He never believed that France would actually bring on hostilities. Still, with his usual forethought, he would have every preparation made — these, in themselves, being often the best means of averting bloodshed. It is a singular fact that he, who in comparative youth was so cautiously prudent, so deliberate in all his military steps, now, at three-score and ten, proposed an entirely different {66} course. The French soldier was a different man from the British soldier; a different course must be adopted with him. He chose for his generals the boldest and most daring spirits among the military men of the country, to plan a series of rapid movements, continued attacks: “The enemy must never be permitted to gain foothold on our shores.”

Thus passed away the months of summer and of autumn. With early winter a solemn change was at hand.

On Friday, the 13ᵗʰ of December, light clouds were gathering over the banks of the Potomac, and the plantation of Mount Vernon. A gentle rain fell. It was the will of Providence that those clouds should become to George Washington the shadows of death. He was abroad, as usual, in the fields. directing the farm-work of the plantation. His long gray locks, falling about his throat, were wet with the rain. Heedless of the fact, he returned home, passing the remaining hours of the day in his accustomed peaceful manner, at the family fire-side. During the night he became alarmingly ill. A very severe affection {67} of the throat came on. From the first he believed that he should die. The usual remedies were employed, but without avail. He lingered some twenty-four hours,and near midnight of Saturday, December 14ᵗʰ, in full possession of his faculties, and in the calmness of Christian faith, he closed his eyes on this world.

The following week, on Wednesday, the 18ᵗʰ of December, he was borne to his grave — a grave opened at a spot chosen by himself, on the grassy hill-side, overshadowed by trees — the Potomac flowing below — the home in which so many honored days had been passed, rising from the brow of the hill above.

There may he lie in peace, guarded by the love of a grateful nation, until the Resurrection of the Just!

Children of America! brief and imperfect as this rapid sketch of a great life must appear to you, it may yet serve in some decree to warm anew your young hearts towards one of the greatest Christian patriots the world has ever seen. In some beautiful countries of the earth, my young friends, there {68} are mountain heights, raising their hoary heads heavenward with so much of majesty, that even a dim and distant view, even a cloudy vision of their greatness, will deeply impress the beholder. Thus it is with the character of George Washington. The more we examine its just proportions, its beautiful points, its great moral power, the more deeply shall we become impressed with its admirable excellence. But even a brief and imperfect view must reveal enough to fill the thoughtful mind with feelings of very deep reverence.

Children of America! We come to you to-day, affectionately inviting yon to take part in a great act of national homage to the memory, to the principles, to the character of George Washington. The solemn guardianship of the home, and of the grave, of General Washington is now offered to us, the women of the country. Happy are we, women of America, that a duty so noble is confided to us. And we, your countrywomen — your mothers, your sisters, your friends — would fain have you share with us {69} this honorable, national service of love. From those of you into whose hands Providence has thrown coin, be it gold, or silver, or copper, we would ask a gift for the purse we are seeking to fill. More than a gift of small amount we should not consent to receive from either of your number. But with far more of earnestness we seek your warm and real sympathy. Whatever you may be enabled to give, be it bright dime, or clean copper, fresh from the mint, we ask that you give it feelingly — as a simple act of love and respect for the memory of the great man. It is the spirit thrown into every work which can alone give it true value. Let us then, my young friends, give to the pious task in which we are working together, a heart and soul, as it were, in some degree worthy of the purpose. Let this work become, on our part, a public act of veneration for virtue — of respect for love of country in its highest form, pure, true, and conscientious — of loyalty to the Union, the vital principle of our national existence. Let it become, for each of us, a public pledge of re{70}spect for the Christian home, with all its happy blessings, its sacred restraints — of reverence for the Christian grave, the solemn mysteries, the glorious hopes, shrouded within it. Let it become a pledge of our undying gratitude to him who lies sleeping so calmly yonder, on the banks of the Potomac. Let it become a pledge of our thankfulness to heaven, for having granted to the country a man so truly great. And, my young friends, let this act become to ourselves a pledge that we shall endeavor — each in the natural sphere allotted to us by an All-wise Providence — to make a worthy use of the life and faculties granted to us by God; a pledge that we shall seek, in truth and sincerity, to follow all just and generous principles — striving to serve our God, our country, our fellow-men, with something of the uprightness, the wisdom, the fidelity, the humility, to be learned from the life of George Washington.

Faithfully your Friend

and Countrywoman,

_____ _____

THANKSGIVING DAY,

Nov. 19ᵗʰ, 1858.

* “The sachem made known to him that he was one of the warriors in the service of the French, who lay in ambush on the banks of the Monongahela, and wrought such havoc in Braddock’s army. He declared that he and his young men had singled out Washington, as he made himself conspicuous, riding about the field of battle with the general’s orders, and had fired at him repeatedly without success; whence they had concluded that he was under the protection of the Great Spirit, had a charmed life, and could not be slain in battle.” — Irving’s Washington, vol. i., p. 336.