First and Last Tales: “Imagination” and “The Lake Gun”

Presented at the Cooper Panel of the 1996 Conference of the American Literature Association in San Diego.

Originally published in James Fenimore Cooper Society Miscellaneous Papers No.7, August 1996.

Copyright © 1996, James Fenimore Cooper Society.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

James Fenimore Cooper’s handful of shorter stories are hard to come by, since they were never included in his “collected works.” In this paper I shall examine two Cooper stories — one from the very beginning of his writing career and the other at its very end.

“Imagination” was probably written in 1821, during a period when Cooper’s work on The Spy had languished. It was published by John Wiley in 1823, along with a truncated second story, as a slim volume entitled Tales for Fifteen, under the pen name of Jane Morgan. 1 There it fills 124 pages, divided into six chapters. Tales for Fifteen made no stir, and “Imagination” was forgotten until 1841, when Cooper — as a favor — allowed Boston publisher George Roberts to reprint it twice. 2 Cooper told Roberts that the tale “was written one rainy day, half asleep and half awake, but I retain rather a favorable impression of it.” 3 The impression was all Cooper retained Roberts had to find a copy for himself. 4 Not until 1959 did the story appear again, in a facsimile edition of Tales for Fifteen, with an introduction by James F. Beard, taken from one of the four known surviving copies of the original; this edition was reprinted in 1977, and remains available to anyone with $50 to spare. 5

Set in 1816, “Imagination” tells how 16-year old Julia Warren, filled with the romantic novels she has read at school, is misled by letters from her girlfriend Anna Miller into believing that she has a secret admirer. Anna, who has moved from New York City to the Genesee River country on the New York frontier, tells Julia that “Antonio” has fallen in love with her, sight unseen, at Anna’s instigation. Antonio is, Anna writes, “just such a man as we used to draw in our conversation at school. He is rich, and brave, and sensible ... his eye, his nose, his whole countenance, are perfect.” 6

Julia is enchanted with the prospect, especially when she learns from Anna that Antonio is the wronged descendant of British nobility, a brilliant scholar, and a military hero. She does not suspect anything (as, I presume, most of Cooper’s readers in 1823 did) even when Anna specifies that Antonio has “fought at Chippewa bled at the side of the gallant Lawrence and nearly laid down his life on the ensanguined plains of Marengo.” 7

Thus infatuated, Julia ignores her duties towards her virtuous cousin Katherine, and slights her likeable but timid neighbor Charles Weston, who really does love her.

Julia becomes ecstatic when her aunt suggests a trip from their home in rural Manhattan Island to Niagara Falls; and Anna, learning of the excursion, writes that Antonio will come to New York in disguise to watch over her secretly during the perils of the journey. As the trip begins, accompanied by the worthy Charles Weston, Julia quickly decides that their rough and unkempt one-eyed coachman Tony is really her beloved Antonio. His every remark, and his every gesture, is interpreted by Julia as a secret message from her disguised lover.

When the travellers break their trip to visit Anna’s home on the Genesee, Julia’s disillusionment is immediate. Anna blandly informs her that Antonio was only a creature of her imagination — “One must have something to write about, you know, to a friend.” Julia recovers from her shock and duly marries the faithful Charles Weston, although, as Cooper concludes, it was more than a year afterwards before she could admit to him “that she had once been in love, like thousands of her sex, ‘with a man of straw.’” 8

Beard described “Imagination” as an experiment in using American materials within the conventions of British domestic fiction, though noting that its “sprightly observation of American middle- class vulgarities, betray a satiric awareness that Cooper did later develop. ... ” 9

That young girls got wrong ideas from novels was, of course, a standard theme of early 19ᵗʰ Century moralists — novels were considered by many as time-wasters at best, and positively pernicious at worst. Cooper had himself tapped into this feeling in his own first novel, Precaution, when he warned against the “irretrievable injury, to be sustained from ungoverned liberty [in reading] in a female mind.” 10

What sets “Imagination” apart from the standard fictional warnings against the evils of fiction, as James Grossman noticed, is that Cooper, in his words, “while apparently repeating the old lesson, has changed it slightly but significantly: the danger isn’t in fiction itself but in mistaking it for life.” 11

“Imagination” thus becomes one of a comparatively few stories exploring the humorous possibilities of romance-fed young girls creating a fantasy world of their own. Two significant English novels in this genre had appeared before 1821: Eaton Stannard Barrett’s widely-read, The Heroine, published in 1813 12, and the more famous Northanger Abbey of Jane Austen, published in England in 1818 but not reprinted in America until 1833. In each, a novel-reading heroine comes to believe that her fantasy world has become reality, and the reader is led to relish the tortuous ways in which she misinterprets everything happening around her.

There is no positive evidence to suggest that Cooper had read either The Heroine or Northanger Abbey, though “Imagination” was written at a time when he was reading many popular novels aloud to his young wife, and eagerly awaiting their arrival from London. 13 We know that, at least in later life, he was familiar with Cervantes’ Don Quixote, that ultimate progenitor of fantasies turned real. 14 Nevertheless, Cooper carries out his satirical purpose with considerable deftness, and “Imagination” can still be read for amusement as well as for scholarship.

After vainly seeking her lover hiding in the shrubbery, or disguised as an organ grinder, Julia decides that he will appear in the form of a coachman, since he has promised to protect her on the trip to Niagara. So when a prospective driver is recommended to her aunt as superior, keen-eyed, younger than he looks and “strong as an ox and active as a cat,” she has heard enough. In Cooper’s words “For ox she had substituted Hercules, and for cat, she read the feathered Mercury.” 15

The coachman, fortuitously named “Tony,” proves to be coarsely dressed, heavily bearded, and wears a patch over one eye. Julia thinks to herself, “no one who had not previously received an intimation that his character was different from his appearance, would at all have suspected the deception.” When Tony assures Julia’s aunt that their horses are “’As gentle as e’er a lady in the land’”, at the same time staring at Julia with his one good eye, “her heart throbbed with tumultuous emotion at the first sound of his voice, and she was highly amused at the ingenuity he had displayed, in paying a characteristic compliment to her gentleness, in this clandestine manner. ... ” 16

And so it goes. Everything the coachman does, however incompatible with his presumed status as a young gentleman, merely reinforces Julia’s belief. As the party nears Schenectady, Julia asks Charles how far they have yet to go. Coachman Tony for the first time addresses her directly: “Four miles, ma’am, there’s the stone,” and points with his whip at a milestone under an oak tree. Julia’s heart leaps, and “she ran over in her mind the time when she should pay an annual visit to that hallowed place, and leaning on the arm of her majestic husband, murmur in his ear, ‘Here, on this loved spot, did Antonio first address his happy, thrice happy Julia’”. 17

Even when Tony proves a coward, Julia’s faith remains unshaken. When the horses shy and almost back the carriage into the Mohawk River, it is Charles Weston who checks the horses until the coachman can recover control of them, and it is Charles who rescues the panicked Julia when she tumbles into the river. 18 But when the coachman’s fail ure to help is criticized, Julia firmly tells her bewildered aunt that “’It was his place, to manage the horses. ... Duties incurred, no matter how unworthy of us, must be discharged, and ... a noble mind will not cease to perform its duty, even in poverty and disgrace.’” 19

Cooper successfully carries Julia’s fantasy world through forty- three pages, until her dream crashes about her in the story’s closing paragraphs. For a fledgling author, “Imagination” is an original, amusing, and well executed tale. It deserves better than the near oblivion to which it has generally been consigned.

If “Imagination” tells us of Cooper’s beginnings as an artist, “The Lake Gun” is one of the last statements of his political convictions. The text is, if anything, harder to find. “The Lake Gun” appeared in an 1850 New York miscellany, The Parthenon 21, compiled by George E. Wood, who had commissioned the story for $100, 21 and again in a similar collection in 1866. 22 It was reprinted in 1932, in a limited edition of 450 copies with an introduction by Robert E. Spiller, 23 but is now out of print.

“The Lake Gun” is almost certainly based on local lore picked up by Cooper while visiting his son Paul, who in the early 1840s attended Geneva College (now Hobart College) at Geneva, at the head of Seneca Lake in central New York. 24 The story is narrated by a man called Fuller, described as “an idler, a traveler, and one possessed of much attainment derived from journeys in distant lands,” 25 who is casually investigating two legends of Seneca Lake. The first legend is of a tree trunk, misnamed the “Wandering Jew,” that has floated upright around the lake since before the arrival of the earliest white settlers, defying wind and current, and seemingly unsinkable. 26 The second is of the “Lake Gun,” a mysterious sound like an explosion of artillery, which is heard at intervals around the lake and cannot be explained by science. 27

One morning Fuller comes upon a young Seneca Indian in loincloth and leggings, gazing out on the lake. The Indian speaks good English, and had graduated from college before returning to live among his people. 28 Now, visiting the lands of his fathers, he sees in the distance what white men call the Wandering Jew. “’It is the Swimming Seneca. For a thousand winters he is to swim in the waters of this lake. ... Fire will not burn him; water will not swallow him up; the fish will not go near him; even the accursed axe of the settler can not cut him into chips!’”

The Great Spirit had established laws by which men should live, explains the Indian, and set seasons when they should not catch fish in the lake. “’But See-wise was one of those who practiced arts that you pale-faces condemn, while you submit to them. He was a demagogue among the red men, and set up the tribe in opposition to the Manitou’”. He told the Indians that they could catch fish whenever they chose. “’The young Indians liked such talk. They loved to be told that they were the equals of the Great Spirit. ... It is sweet to be told that we are better and wiser than all around us. It is sweet to the red man; the pale-faces may have more sober minds. ... ‘”

But See-wise disappeared. Legend said that he speared a great salmon, which had dragged him down to the bottom of the lake. He was never seen again, but soon afterwards the floating tree appeared. It was then that “the lake began to speak, in a voice loud as the thunder from the clouds,” whenever See-wise tried to catch a fish, or to leave the water. 29

At this point the “Lake Gun” is heard, and accompanied by the Indian Fuller sails out in the lake to find the floating tree. After a search they find it, floating upright, “the end of the trunk” bearing “a certain resemblance to a human countenance,” and even “that of a demagogue. The forehead retreated, the face was hatchet-shaped, while the entire expression was selfish, yet undecided.”

“’We see here,’” explains the Indian, “’the wicked See-wise. The Great Spirit call him Manitou, or call him God does not forget what is wrong, or what is right. The wicked may flourish for a while, but there is a law that is certain to bring him within the power of punishment. ... But Indians like this Swimming Seneca do much harm. They mislead the innocent, arouse evil passions, and raise themselves into authority by their dupes. The man who tells the people their faults is a truer friend than he who harps only on their good qualities. ... Accursed be the man who deceives, and who opens his mouth only to lie! Accursed, too, is the land that neglects the counsels of the fathers to follow those of the sons!’

“’There is,’” responds Fuller, “’a remarkable resemblance between this little incident in the history of the Senecas and events that are passing among our pale-faced race of the present age. Men who, in their hearts, really care no more for mankind than See-wise cared for the fish, lift their voices in shouts of a spurious humanity, in order to raise themselves to power, on the shoulders of an excited populace. Bloodshed, domestic violence, impracticable efforts to attain an impossible perfection, and all the evils of a civil conflict are forgotten or blindly attempted, in order to raise themselves in the arms of those they call the people.’”

“’I know your present condition,’” concludes the young Indian, smiling. “’The Manitou may have ordered it for your good. ... There are days in which the sun is not seen when a lurid darkness brings a second night over the earth. It matters not. The great luminary is always there. There may be clouds before his face, but the winds will blow them away. The man or the people that trust in God will find a lake for every See-wise.’” 31

Thus ends the political parable of “The Lake Gun.”

The fate of See-wise suggests Ben Pump’s misadventure in the fishing scene in The Pioneers. 31 More significantly, the hiding of the sun during the period of the Manitou’s disfavor recalls the “literal” moral eclipse in the concluding chapters of The Monikins, 32 and Cooper’s own description of a solar eclipse in 1806 as seeming “as if the great Father of the Universe had visibly, and almost palpably, veiled his face in wrath.” 33

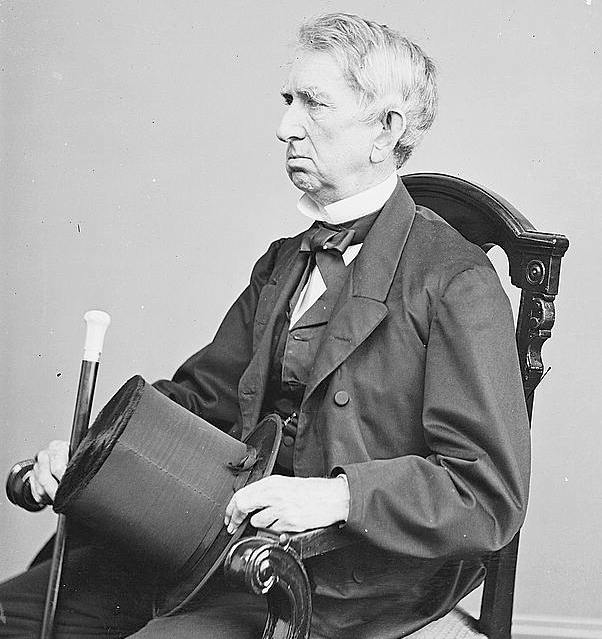

William Henry Seward, Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018666383/.

Like “Imagination,” few Cooper scholars mention “The Lake Gun,” and fewer have examined it. Those who have, notably Robert Spiller and George Dekker, concur that Cooper’s “See-wise” is intended to represent, at least in part, William Henry Seward. Seward, a leader of the radical faction of the Whig Party, had been Governor of New York, was in 1850 a Senator, and would eventually become President Lincoln’s Secretary of State. Not only is Seward’s name suggested by the name “See-wise,” but his well-known angular face and prominent nose suggest the hatchet-shaped physiognomy seen on the floating tree. 34

In the same year that “The Lake Gun” appeared, Cooper began writing a never-completed history of New York City, to be entitled The Towns of Manhattan. 35 In a surviving preface published only in 1864, he expressed his belief that America was “governed, in fact, not by its people, as is pretended, but by factions that are themselves con trolled most absolutely by the machinations of the designing.” 36 This had thrown “the political power of the entire Republic into the hands of the intriguer, the demagogue, and the knave.” 37 For James Fenimore Cooper, Senator Seward was the very epitome of the demagogic knave. Like his political mentor Thurlow Weed, himself a longtime political antagonist of Cooper, Seward recognized, in George Dekker’s words, that Whig success in the 1840s depended on “cultivating the good will of two opposed factions: the affluent but conservative commercial classes, for their contributions to party funds; the newly enfranchised masses, for their votes.” 38 To Cooper this was the ultimate corruption of Constitutional government.

Cooper opposed slavery; in the same uncompleted 1850 preface to The Towns of Manhattan cited above, he wrote that “The institution of domestic slavery cannot last,” and went on to deny that the Constitution protected either slavery or a right to secession. But Cooper accepted the 1850 Compromise and the Fugitive Slave Law, and believed that abolitionist agitation was ineffective and even counter-productive. He looked to common sense to avert civil war, and believed that “A century will unquestionably place the United States of America prominently at the head of civilized nations, unless their people throw away their advantages by their own mistakes. ... ” 39

But “The Lake Gun” is not just directed against William Seward. It is also Cooper’s last warning against the looming menace of an American Civil War, with “bloodshed, domestic violence ... and all the evils of a civil conflict.” “The Lake Gun” appeared in November 1850 ten months later, Cooper was dead.

I hope that this brief exploration of Cooper’s first and last tales demonstrates that they are worthy of consideration in our study of his dual career as a literary artist and as a critic of his times.

Notes

1 “Jane Morgan,” Tales for Fifteen (New York: C. Wiley, 1823) [facsimile edition, with an Introduction by James F. Beard: Gainesville, FL: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 1959; second printing, Delmar,NY, 1977]. One of five projected moral tales Cooper had promised New York publisher Charles Wiley, it was the only one to be fully completed. A hastily concluded version of the second projected tale, “Heart”, was included in Tales for Fifteen; the other three,to be called “Matter,” “Manner,” and “Matter and Manner,” never materialized. See James F. Beard, Introduction to Tales for Fifteen, viii-ix.

2 See James F. Beard, Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960-68), Vol. IV, 109 n. & n.3. They appeared in Roberts’ weekly Boston Notion (Jan. 30, 1841) and in his newly-founded Roberts’ Semi-Monthly Magazine (Feb. 1 & 15, 1841. The Boston Notion, subtitled “The Mammoth Sheet of the World,” had pages 34 x 50 inches in size; “Imagination” filled the entire front page. “Imagination” appeared in British anthologies in 1841 and 1842. See Robert E. Spiller & Philip C. Blackburn, A Descriptive Bibliography of the Writings of James Fenimore Cooper (New York: R.R. Bowker, 1934 [facsimile edition: New York: Burt Franklin, 1968] 32-33.

3 Letter of Jan. 2, 1841 to George Roberts, in Beard, Letters ... , Vol. IV, 107-108.

4 Beard, Introduction to Tales ... , x-xi.

5 See note 1, supra.

6 Tales ... , 25, 46.

7 Tales ... , 47. A peculiar military career, indeed, as Cooper’s original readers — unlike the infatuated Julia — would presumably have noticed. American troops defeated the British at Chippewa in what is now Ontario on July5, 1814; Capt. James Lawrence was mortally wounded in the naval battle between the Chesapeake and the Shannon off Boston harbor on June 1, 1813; and Napoleon defeated the Austrians at Marengo on June 14, 1800.

8 Tales ... , 122, 124.

9 Beard, Introduction to Tales ... , xii.

10 James Fenimore Cooper, Precaution (New York: A.T. Goodrich, 1820) [facsimile edition: New York: AMS Press, 1976] Vol. I, 242. Indeed, Alan Taylor has suggested that Cooper’s beloved older sister Hannah, who died in 1800, sought to model herself on the heroines of English sentimental fiction; see his William Cooper’s Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995), 303-305.

11 James Grossman, James Fenimore Cooper (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1949), 35.

12 Eaton Stannard Barrett, The Heroine; or, The Adventures of Cherubina (London: 1813). The Heroine was quickly pirated in America, with editions published in Philadelphia and New York in 1815 and in Boston in 1816. My copy was published by Robert F. DeSilver in Philadelphia, in 1834.

13 See Susan Fenimore Cooper on the genesis of Precaution, in Pages and Pictures from The Writings of James Fenimore Cooper (New York: W.A. Townsend & Co., 1861), 16-17.

14 Epigraph, The Monikins (1835), Title page.

15 Tales ... , 78-80.

16 Tales ... , 92-93.

17 Tales ... , 103.

18 Tales ... , 109-115. Cooper would include a similar scene in The Pioneers (1823), when a disguised Oliver Edwards rescues a sleigh being backed over a precipice by the incompetent Richard Jones.

19 Tales ... , 114.

20 Spiller & Blackburn, Bibliography ... , 204.

21 Letter to Mrs. Cooper, Nov. 25, 1850 (“I am finishing off the ‘Lake Gun’ which earns the $100, that lies untouched in my trunk. I should like to work at this rate, the year round. ... “), in Beard, Letters ... , Vol. VI, 238-240.

22 In Specimens of American Literature (New York: 1866), cited in Spiller & Blackburn, Bibliography ... , 61.

23 James Fenimore Cooper, The Lake Gun (New York: William Farquhar Payson, 1932)

24 Paul Fenimore Cooper (1824-1895) attended Geneva College (now Hobart College) from 1840 to 1844, graduating as Class Valedictorian on Aug. 7, 1844; in 1847 he was awarded a Masters degree. Cooper addressed the Geneva graduation exercises in 1841 (the talk, attacking “public opinion,” was denounced with venom by “a correspondent” in The New-Yorker of Aug. 14, 1841). He was unable to attend his son’s graduation in 1844. See Letters and Journals ... , Vol. IV, 52, 124, 389, 468. Cooper visited Geneva for several days in October 1843 (ibid, Vol. IV, 417), in July 1849 (ibid, Vol. V, 373), and in October 1849 (ibid, Vol. VI, 76).

25 The Lake Gun, 30. Fuller (“for so we shall call the stranger for the sake of convenience”) seems clearly to be intended as Cooper himself.

26 The concept of an unsinkable log floating in Lake Seneca remains of obscure origin, and a search of published Seneca folklore and inquiries to a knowledgeable Seneca storyteller (Deuce Bowen) have not turned up any authentic Indian predecessor. At least two legends embodying the concept seem to have been current at Geneva College on Lake Seneca during the 1840s, and Cooper may well be combining them.

The first appears as “Outalissa, A Tradition of Seneca Lake,” by the New York poet and Episcopal Minister the Rev. Ralph Hoyt (1806-1876). “Outalissa” first appeared in pamphlet form as Sketches by Rev. Hoyt, Vol. VIII (New York: C. Shepard, ca. 1848). In a preface, Hoyt says “A large tree has been floating up and down this beautiful lake (Seneca), during many years, and it is now regarded with much interest by the ancient dwellers of the neighborhood, from whom the writer gathered the wild tradition concerning it” that he has embodied in the poem.

“Outalissa” tells of a white man lost near Lake Seneca, who is given hospitality by the aged Seneca Chief Outalissa. Next morning, prophesying that Indians will be bloodily dispossessed by the whites, and fearing for his young daughter, Outalissa asks the stranger to swear and oath on the great Council-Tree to be “the Indian’s friend.” The white man does so, but later in the day, seeing Chief Outalissa asleep under the tree, decides to speed up the prophecy and rolls the slumbering Chief into the lake to drown. The Manitou sends down a thunderbolt which blasts the Council-Tree and treacherous white man together, and throws both into the water. The “villain white” sinks to the bottom, but the Council-Tree begins “its long wandering”, to float for a thousand moons as evidence that “I saw great Outalissa Slain.” I am indebted to Archivist Charlotte Hegyi of the Warren Hunting Smith Library, Hobard and William Smith Colleges, Geneva, New York, for calling my attention to this poem (as well as other information about Cooper and Geneva College); the copy of “Outalissa” acquired by Geneva College, tentatively dated 1848, bears the signature “C.P. Delancy.” This is intriguing, since Cooper’s brother-in-law, Rev. William Heathcote De Lancey (1797-1865) became Episcopal Bishop of Western New York in 1839, and lived in Geneva; I cannot, however, identify any member of his immediate family with the initials “C.T.”

A different version is known as “The Floating Chief,” and became part of Geneva College folklore. A Seneca Indian Chief named Agayentha, caught in a thunderstorm while tracking a bear along Lake Seneca, took refuge under a tree. The Seneca God of Thunder struck down both tree and chief, and flung them into the water; the next day, as another storm approached and thunder was heard, there appeared “the trunk of a tree, erect and protruding two feet out the water,” which ever since has floated around Lake Seneca “like a funeral barge” whenever a storm approaches. Chief Agayentha became a college icon, to be invoked by Hobart College athletic teams. “Clumsy white men” later renamed the Floating Chief as The Wandering Jew, adopting the medieval European tale of Ahasueras, who scoffed at Jesus and was condemned to live until the second coming. This tale has been recorded by folklorist Arch Merrill in a number of books and articles: The Lakes Country (Rochester: Louis Heindl & Co., [1944]), 77; Land of the Senecas (New York: American Book-Stratford Press, [1949]), 74-75; Slim Fingers Beckon (New York: American Book-Stratford Press, [1951]), 84-85; Our Goodly Heritage (New York: American Book-Stratford Press, [1956]), 23; “Old Legends Never Die”, New York Folklore Quarterly, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring 1957), 55-56.

27 The Lake Gun legend seems better known than that of The Floating Chief. The mysterious booming of the “Lake Gun” (sometimes “Lake Drum”) is heard on Cayuga Lake as well as on Seneca Lake, and has been given a variety of literary, folkloric, and scientific interpretations. See, e.g., A.M. Drummond, “The Lake Guns of Seneca and Cayuga: A Dramatic Legend of the Finger Lakes Country,” in A.M. Drummond & Robert E. Gard, eds., The Lake Guns of Seneca and Cayuga and Eight Other Plays of Upstate New York (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1942), 11-73. Folklorist Arch Merrill (see above), like Cooper, weaves “The Lake Gun” into the legend of the “Wandering Chief.” The Public Radio Station WSKG in Binghamton, New York, in the fall of 1995, produced an excellent program reviewing various accounts of the “Lake Gun,” though it did not include “The Wandering Chief” legend or Cooper’s story.

28 The Lake Gun, 43. The Indian is undoubtedly modelled after Abraham La Fort (De-hat-ka-tons), an Onondaga Indian Chief who, under the influence of Joseph Brant, attended Geneva College in the late 1820s, but later abandoned Christianity and returned to his traditional life-style. See Warren Hunting Smith, Hobart and William Smith: The History of Two Colleges (Geneva: Hobart & William Smith Colleges, 1972), 39-40.

29 The Lake Gun, 40-48.

30 The Lake Gun, 52-54.

31 James Fenimore Cooper, The Pioneers (New York: Charles Wiley, 1823), Vol. II, 79-82.

32 James Fenimore Cooper, The Monikins (Philadelphia: Carey, Lea and Blanchard, 1835), Vol. II, 184ff. (Chapters 27-29 in later one-volume editions).

33 James Fenimore Cooper, “The Eclipse,” (Putnam’s Magazine (Sept. 1869), 358. In this essay (352-359), written about 1836 but published only posthumously, Cooper describes his feelings, as a 16-year old boy back home in Cooperstown after being expelled from Yale, during the total solar eclipse of June 16, 1806, feelings morally heightened by his visit, while waiting for the eclipse to begin, to see Stephen Arnold, a school-teacher awaiting a possible death sentence for fatally abusing a child, who had been allowed out of his dark dungeon for the first time in a year to see the event. On the Arnold case, see Louis C. Jones, “The Crime and Punishment of Stephen Arnold,” New York History, Vol. 47, No. 3 (July 1966), 248-270.

34 Robert F. Spiller, Introduction to The Lake Gun, 16-18; George Dekker, James Fenimore Cooper: The Novelist (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1967), 241.

35 The Towns of Manhattan was never completed; the surviving preface was serialized in the daily The Spirit of the Fair, issued in April 1864 by the Metropolitan Fair in New York City, to raise funds for the Sanitary Commission (a predecessor of the Red Cross). It was reprinted in 1930 as New York, with an introduction by Dixon Ryan Fox (New York: William Farquhar Payson, Limited edition of 750 copies, 1930) [facsimile ed. of 100 copies, Folcroft, PA: Folcroft Library Editions, 1973]}.

36 New York, 38.

37 New York, 43.

38 Dekker, op cit., 238.

39 New York, 19 ff, 32-34, 37.