The Last of the Mohicans, Cooper’s Historical Inventions, and His Cave

Paper presented at the Eighteenth Annual Meeting of the New York State Historical Association, October 3-5, 1916, Cooperstown, New York. .

Published in Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association, Vol. XVI (1917), pp. 212-255.

Placed online with the kind authorization of the New York State Historical Association.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

Transcribed as printed; a few apparent errors are signaled by {curly braces}. I have renumbered the footnotes consecutively, and added to (clearly identified) Mr. Holden’s information. I have also inserted five of the many photographs that accompanied the original publication.

— Hugh C. MacDougall

The primary purpose of the historical fictionist is of necessity the entertainment of his readers; a secondary purpose is that of improving their minds. As the poet has always been allowed a certain license in describing scenes and portraying characters, as the artist is granted a free range in his depiction of things human, natural and divine, so the novelist, their fellow workman of the pen or pencil, is given a wide latitude in presenting in printed form, the product of his imagination, even though it he based on the solid rock of history.

In this way errors are spread broadcast, and in the lapse of time, because they “have read it in a book,” people believe fiction to be history, and it may be oftentimes, history to be fiction.

The historical novels of J. Fenimore Cooper have preserved to this day such a degree of attractiveness and such a sugar coating of the cut and dried facts of life, that perhaps their historical anachronisms and inaccuracies have not been clearly perceived by the ordinary reader. Some of these it is my intention to try to correct in this necessarily imperfect and possibly ungraciously conceived paper, for who are we, to endeavor to rectify the mistakes of a master mind, made nearly a century ago, and so firmly imbedded in popular opinion as to be almost permanent beliefs?

When, however, we remember that, even after nearly a century, Cooper’s most famous or at best most popular novel, the “Last of the Mohicans,” is still a favorite in this country and abroad, and that even in 1917 the Syllabus for Secondary Schools in English Language and Literature, intended as a guide for Regents examinations in New York State, places this work first in “group 2” of the books required to be read by pupils in our public schools, before examinations in English and literature, it would seem fitting and allowable for a historian to call attention to the author’s obvious misstatements of historical incidents. But, more than all this, born in the village made more than locally celebrated through the “Last of the Mohicans,” within hearing of the thunderous music and soothing diapason of the falls in flood, son of the local historian of the town and county, and for five years state historian of New York, acquainted with the treasured lore of history, tradition and legend, not only in his father’s possession, but common to the locality, the writer since his childhood days has known and familiarized himself with story and spot and place of the French and Indian Wars, till they have become woven into the web and woof of his existence, and a part of his conscious life, in Glens Falls.

Feeling therefore a sort of proprietary right in this historical region, the so- called “war path of the nations,” the writer feels it is proper for him to call attention to the errors of Cooper most evident to the local historian. Those to which the writer will devote the most space in this article, are: first, an anachronism in a local name; second, a pure invention in the designation of a locality, leading to a worldwide error; and third, a fictitious representation of what has but lately been shown to be a family with an actual existence, although proofs were as available then as now, especially to a visitor to the British Isles.

In chapter 5 of the “Last of the Mohicans” Hawkeye tells Heyward: “You are at the foot of Glenn’s,” thus giving to the cataract a name it did not attain until over a quarter of a century later, after the Revolution had spent its force and activity in this region. And this in spite of the fact it had recognized and available Indian names which Cooper might have used.

Again, throughout the book, Cooper has bestowed upon the beautiful waters of Lake George the purely imaginary name “Horican,” which, spread abroad and at home by thousands of visitors to this storied lake, has perpetuated a historical error in nomenclature that ages evidently will fail to correct.

In the third place, when Cooper gave to Captain Munro two lovely daughters, he did not imagine, nor has anyone else, the gallant officer as having an actual family; and it has been within only a short period of time, and by the investigation of a correspondent of this association, that a gleam of light has been cast upon his true life, showing Cooper’s master touch at fault, not so much in treatment as in details.

Of course all these faults are trivial in themselves except as they have served to perpetuate errors, and to transmit to posterity that which Cooper was ever the first to criticise and condemn in others, inaccuracy and imperfectness of description. I shall try if possible therefore in this article to throw some new lights on the story which for so many years has, for good or for ill, {has} gone its way, entertaining, delighting but misinforming our youth and their elders, under the name, “The Last of the Mohicans.” In order to bring out more clearly my meaning, I shall have to go into local history and possibly be overdiscursive to prove my contentions and to correct such mistakes as I feel it essential to touch in this paper.

The Falls, 1896.

First, as to Glens Falls, which play, with the cave, so large a part in the narrative of the “Last of the Mohicans,” 1 There is little doubt that this fall or series of falls was known to the Amerinds for years before the white men came into this region. Men of the St. Francis tribe, descended from the old Algonkin stock, many years ago told my father, Queensbury’s historian, that these falls were called “Che-pon-tuc,” “a difficult place to climb or get around,” 2 or, as A. C. Parker, New York State Archeologist, translates it, “big walk [around] a stream.” Another name was “Pan-gas-ko-link,” meaning, as near as Mr. Parker desires to anglicise it, as he thinks the name a corrupt one, “a ford near a fall,” which would apply to the place of crossing just below the falls. Still another was “Ka-yan-do-ros-sa,” which Doctor Beauchamp says has been defined by A. Cusick as “long deep hole,” in allusion to the ravine. 3 This word, however, is so easily confused with the name of the entire region of “Ka-ya-de-ros-se-ras,” the “lake country,” I question its propriety in the application to the Glens Falls cataract, as it really means “where the lake empties,” or “mouths itself out,” and is applicable in this sense to Fish creek or the outlet of Saratoga lake.

In the earlier colonial periods the ebb and flow of battle came to high tide on the plains of Schenectady and Saratoga and receded on the Hudson’s banks, at the big bend above the falls, when the defeated Algonkins sped northward before the avenging Dutchmen and their Mohawk allies. Neither savage nor civilized outpost then marked the lower Adirondack wilderness, crossed only by the hard-beaten trails of savages, two footed or four, alike in their ferocity and cunning.

.

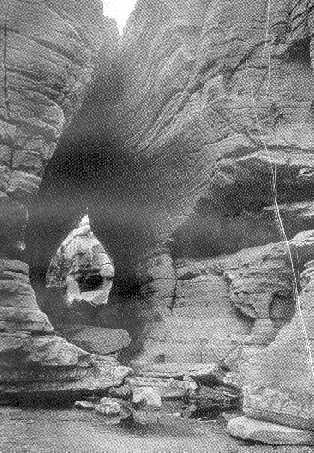

The cave, showing rocks split off by erosion.

In 1755, the pioneers of Sir William Johnson carved brood and deep their military road out of the virgin forest between Forts Lyman and George, never {ever?} since then overgrown or fallen into disuse. After the exciting days of the French and Indian Wars, the territory was opened up to white settlers, and in 1763, Abraham Wing, of the Oblong, his relatives, dependents and servants, removed here from Dutchess county, founded the town Of Queensbury, and constructed sawmills and established other enterprises at the falls, which naturally became “Wing’s Falls,” and so remained until long after the Revolution. 4 The gathering of houses, stores and business places on the plateau above was variously called “Wing’s Corners” or “The Corners.”

In 1788, as the result of — some say in payment for — a “wine supper for the entertainment of mutual friends,” according to others, members of the family, in consequence of a bargain by a wayward son which his father felt in honor bound to ratify, the pioneer, Wing, sold his name-right in the falls to Colonel John Glen of Schenectady, who had bought water rights and erected sawmills on the south bank of the river. Issuing posters announcing the change of name, Colonel Glen soon notified everyone from Queensbury to Albany of the new name of the falls, which from April 29, 1788, was Glen’s Falls, and such has since remained. 5 For a time the principal hamlet Was called Glenville and also Pearl village, but about 1833 6 the former was changed to its present name. For a little while it was spelled Glenn’s, but soon lost the extra “n,” and in the late seventies or early eighties, the post-office department eliminated the apostrophe, leaving the name as it is at present.

It will be noticed, therefore, that in 1826 Cooper refers to the “Falls at Glenn’s,” but, manifestly, improperly and incorrectly, as Colonel Glen did not come into this section unless during his services as a quartermaster in the French and Indian Wars, 7 and had no proprietary rights until about 1775. Nor were there mills, nor was there a settlement, nearer than that of Lydius 8 in the French and Indian Wars of a decade or so earlier.

Cooper, therefore committed an anachronism here, when he might easily have used either of the Indian names, “Che-pon-tuc” or “Ka-yan-do-ros-sa,” with equal force and to as good effect.

How and why the “Last of the Mohicans” came to be written is an interesting story in itself, and one not without its local interest. Those familiar with the life of James Fenimore Cooper will remember the almost instantaneous success of “The Pioneers,” which introduced “Natty Bumppo” as a new and distinct type to American and foreign readers of fiction, a character often imitated, but never surpassed or even equaled by novelists since Cooper’s day, in the minds of able critics. Probably no greater pen pictures of Indian or backwoodsmen’s life have ever been produced than those in the quintette of novels known as the “Leatherstocking Tales,” in which Cooper carried his likeable, entertaining, manly and brave hero from virile youth to feeble, decrepit old age.

But, to return to that one in which he, in the turn of the wheel, touches also the periphery of our own locality and the birthplace of our association. It was in the summer of 1825 8ª, according to Susan F. Cooper, but of 1824 according to Professor Lounsbury, that a happy, care-free group of young men fore-gathered in New York, and began a slow but pleasant journey up the Hudson, stopping at West Point and Catskill on their way, striking across to visit the Shaker settlement at Lebanon, thence visiting friends in Albany, and by easy stages taking in the even then “gay” life at the health-giving springs of Ballston and Saratoga. Of his visit to the spring at the former place, Cooper, a member of this group, later on made good use in his story.

From Saratoga, by the medium of the clumsy old coaches of the day, the party made its way to Lake George, passing over the piny plains of Saratoga, by Mount McGregor, over the toll bridge at Glens Falls, over the passable but sandy road, by Meadow Run and Bloody Pond, later to be utilized in the story, 9 until at last, as to many a traveler since, the “Holy-lake,” as Cooper termed it, burst into view, on their right, and the party saw as on some great canvas, its azure blue depths, crowned with green-girt islets and masses of rugged land, surrounded by the dark evergreens, by maples, chestnuts and living oaks bright in their summer verdure, rising in serried ranks from the water’s side to the hilltops encircling the lake. With such a setting no wonder the novelist’s mind perceived a picture here which he could and would use to advantage later.

In Cooper’s party were the Hon. Mr. Stanley, later to become eminent as Lord Derby, Prime Minister of England, and the Hen. Wortley Montague, the Lord Wharncliffe of succeeding years. Who else was in the company, history and Cooper’s biographers have failed to record 9ᵃ although his daughter says some half dozen comprised the traveling party. 10

In connection with the visit to Lake George, I discovered among my father’s manuscripts a historical essay delivered in 1885, 11 from which I have taken the following: “About 1825, James Fenimore Cooper, the novelist, visited this section of country, with a view to familiarize himself with the scenery and roadways and perfect the details of a plan he had framed for a novel. During a great portion of this time he was the guest of the Hon. Peletiah Richards 12 at Warrensburgh, who hospitably afforded him every opportunity for investigation and inquiry.”

Second, in connection with Cooper’s visit to Lake George, we will take up here the consideration of the name of “Horican” which the novelist gratuitously bestowed upon the beautiful sheet of water, and to trace if we can its origin.

In the manuscript alluded to before, Doctor Holden states that the lake had four names, namely, An-di-a-ta-roc-te, 13 given it by the Iroquois according to Father Jogues, and meaning “the place where the lake contracts,” Can-i-de-ri-oit, 14 “the tail of the lake” (Champlain), supposed to be a Mohawk term, Lac du St. Sacrement, “lake of the blessed sacrement,” { sic} given it by Father Jogues in 1646, 15 and Lake George, in honor of the reigning monarch, bestowed by Major General William Johnson in 1755, in honor of his king. 16

Whence then did Cooper derive the name, Horican? Up to about 1850 his readers might have supposed the name authentic and appropriate, as Cooper’s preface, till then, said nothing about it. Doctor Holden is authority for the statement that, while on his trip to Lake George, a visitor to, or being entertained by, Mr. Richards, he learned of an old map in the historical archives of Albany, later published in the “Documentary History of New York,” upon which he found the name of a tribe of Indians situated about the center of the New England states, called “the Horicans.” “The name,” Doctor Holden says, “was novel, euphonious, and tickled his fancy, so he seized upon and appropriated it for the name of this lake.” The name does not therefore mean “silvery water” or anything else it is commonly supposed to mean.

In the edition of his works published about 1851, however, Cooper relieved his conscience, if such were necessary for a novelist, by this confession, which ever since has appeared in the regular preface to his works, although not in the original one of 1826:

“There is one point on which we wish to say a word before closing this preface. Hawkeye calls the Lac du Saint Sacrement, the ‘Horican.’ As we believe this to be an appropriation of the name that has its origin with ourselves, the time has arrived, perhaps, when the fact should be frankly admitted. While writing this book, fully a quarter of a century since, it occurred to us that the French name of this lake was too complicated, the American too commonplace, and the Indian too unpronounceable, for either to be used familiarly in a work of fiction. Looking over an ancient map, it was ascertained that a tribe of Indians, called ‘Les Horicans’ by the French, existed in the neighborhood of this beautiful sheet of water. As every word uttered by Natty Bumppo was not to be received as rigid truth, we took the liberty of putting the Horican into his mouth, as the substitute for ‘Lake George.’ The name has appeared to find favor, and, all things considered, it may possibly be quite as well to let it stand, instead of going back to the house of Hanover for the appellation of our finest sheet of water.

“We relieve our conscience by the confession, at all events, leaving it to exercise its authority as it may see fit.” 17

This statement of Cooper should be proof conclusive of the lack of any historic value in the name. His daughter, Susan Fenimore Cooper, in her special introduction to the work endeavors, however, to show her father’s fidelity to historical fact, and quotes authorities and details to prove her contention, although no where does she show that Cooper ever saw any of the rare and at that day hard to consult authorities which she quotes nearly a quarter of a century after his death.

As one authority states, 18 Cooper did not invent the name, but transferred it, which I think covers the ground completely.

It may be of interest, however, and fair to all to see just what authorities for the name do exist, even if no evidence is at hand that Cooper ever saw them.

It is doubtful whether Cooper, beginning his work, as he did, on the shores of Long Island, and completing it probably at his home then at 345 Greenwich street, New York City, afflicted a part of the time with a serious and threatening illness, paid any attention whatever, in writing the “Last of the Mohicans,” to historical accuracy, or thought much about the subject. The work was rapidly composed and published early in January 1826, substantially as it now is, to meet with an unqualified popularity, which has continued even to this day.

The map which Doctor Holden supposed had supplied Cooper with his name for Lake George, was at the time believed to be one of the oldest maps of the province extant. It was engraved by Lucini, an Italian, and before the fire of 1911 was in the map collection of the New York State Library. 19 It shows the “Horicans” at latitude 42 and inland from “the gulf of Plymouth.” 21 Doctor O’Callaghan believed this map, though undated, to have been engraved about 1631. 21 More modern authorities, however, would place its construction around 1639 or 1635, 22 or perhaps even a little later.

There were other old maps of the New England and New Netherland regions which might have been available for Cooper’s use, but even today some of these are scarce and rare, except in reproductions, so that their accessibility in 1826 is extremely doubtful.

Among them was Nicholas J. Visscher’s map of the New Netherlands, published in 1655, which shows the “Horicans” located somewhere near Buzzards bay, not far from latitude 41 in southeastern Massachusetts, the “Moricans” near the mouth of the Fresh river, and the “Horikans” established toward the upper reaches of the Fresh (Versche), now called the Connecticut, river, between latitude 43 and 44. They, with the river, are placed, however, to the westward of Lake Irocosia, or Champlain, on the map instead of the eastward, as they should have been.

Here is an embarrassment of riches, where we have “Horicans” and “Horikans,” to say nothing of “Moricans,” to choose from, 23 each one located many miles away from the others.

Next we have Adriaen vander Donck’s map of the New Netherlands, published in 1656, 24 which shows a tribe called Horikans on the upper reaches of the Versche (Fresh) river (the Connecticut) about opposite “Fort Orange” (Albany) and “Colonye.”

It seems strange that vander Donck did not describe the various nations named on his map, as he has given us a very good pen picture of the New Netherlands in his “Representation” of 1650, with a description of the “Fresh river.” 25

Miss Cooper, in her introduction to the Houghton and Mifflin edition of Cooper of 1896, has tried to show that the Dutch writer, DeLaet, places the tribe of the Horicans near Lake George. I do not read the passage in the same way, nor do I agree with her conclusions.

De Laet says, in his New World, in chapter 8: “Next on the same south coast, succeeds a river named by our countrymen Fresh River [the Connecticut] ... at the distance of fifteen leagues ... nation is called Sequins. From this place the river stretches ten leagues, mostly in a northerly direction, but is very crooked; ... the natives there ... are called Nawaas. This place is situated in latitude 41º 48’. The river is not navigable with yachts for more than two leagues farther, as it is very shallow and has a rocky bottom. Within the land dwells another nation of savages who are called Horikans; they descend the river in canoes made of bark.” That is the present Connecticut river, not the Hudson.

Since preparing the foregoing the writer has been fortunate to find 26 in the New York State Library a copy of the rare 1630 edition of DeLaet’s “Beschryvinge van west Indien.” 27 In this the original passage runs: “Binnen in het landt woondt een ander natie van Wilden welck sy noemen Horikans, die dese rivier af komen met canoen van basten ghemaeckt.” This, A. J. F. van-Laer, New York State Archivist, has translated as follows: “In the interior of the country dwells another tribe of Indians whom they call Horikans, who come down the river in canoes made of bark.” This it will be noted closely corresponds with the rendering given in Jameson, it being kept in mind the river in question is the Connecticut of today.

In this old Elzevir edition are two rather interesting maps of collateral interest, on one of which, 28 showing about latitude 45-46, are two unnamed bodies of water similar in shape to Lakes Champlain and George. Beyond these are two other bodies somewhat similarly joined together, one marked “Grand lac,” the other “lac des Yroquois,” On the other map, however, between latitude 43 and 46, are two bodies of water joined together to form “Lac de Champlain” and {“}Yroquoys,” 29 which more nearly resemble in location and shape those we are familiar with.

It is plain from an examination of DeLaet’s description, therefore, that by no possibility of translation can the Horikans (with a “k”) be transferred except by force to the Lake George region 31 from the Fresh or Connecticut River, down which “they descend in bark canoes.”

After describing the “Fresh” river, DeLaet gives a description of the “Great river” (the Hudson), as far as “Fort Orange” (Albany). He mentions the Mackwaes (Mohawks), the enemies of the Mohicans, but in no way describes the Horicans, as being located in this section, and certainly not in the vicinity of Lake George as Miss Cooper intimates. 31 Had they been there, DeLaet would undoubtedly have mentioned them, as they would have been the natural enemies of the Iroquois, or Mohawks. 32

The English publisher, John Ogilby, shows the “Horikans” on the upper reaches of the Versche river on his map ” Nova Belgii Tabula,” 1670, in his folio atlas of America, but it is evidently copied from the earlier Visscher map, showing the same inaccurate placing of Lake Irocosia to the east of the Connecticut instead of the west and about opposite the latitude of “New Albany” and “Colonye” on the Hudson. 33

In Louis Hennepin’s work, “A New Discovery of a Vast Country in America,” in the map at the beginning of the book, is shown what purports to be the region now known as northern New York. The map is neither accurate nor plainly indicated, but near the headwaters of the Hudson and Lake George and Champlain appears the name “Horican.” The query is: Did Cooper refer to this map or some of the others mentioned? Hennepin does not appear ever to have seen Lake Champlain or Lake George, his travels being in the western part of the State, in Ohio, the farther west and the south, and his information touching eastern New York was largely derived from others. His knowledge was second hand, although his map may be good enough for a novelist’s purposes. As a geographer, Hennepin has been rather savagely attacked by historians, and his text assailed as to its accuracy. 34

On the subject of the Mahikans, Dr. W. M. Beauchamp has said: “The Mahikans were the most northern nation of the Algonquin family in New York, occupying both banks of the Hudson and for some distance west along its upper waters. Saratoga was once in their territory. They claimed the land for two days’ journey west of Albany and farther south their claim was good. Their southern limits were below the Catskills, and some place them still farther south. South of these were several small nations of this family, whose names and locations are somewhat confused.” 35 It will be noted that Doctor Beauchamp, in assigning to the Mahikans an occupation so northerly, nowhere designates them as Horicans.

In considering this matter too, it must be remembered that the original inhabitants of the Lake George region were called “Adirondacks,” or tree-eaters. An old Jesuit Relation says in describing this region: “We find here also the Adirondacks, that is to say, eaters of trees. This name has been given them by the Iroquois in ridicule for their fasting while on the chase (hunting). It has been changed more slowly into that of Algonquins.” 36 In neither Father Jogues Narrative nor any of the Jesuit Relations so far as examined does the name of “Horican” appear as a tribe, location or name in the Adirondack wilderness.

John Gilmary Shea has a plausible version of the name. In speaking of Lake George he says: “This is now called Lake George, after one of the worthy monarchs of the name. Some old map had Horicon for Hirocoi, and the misprint has been metamorphosed into a name for the lake. ... ” 37

Evidently Francis Parkman agreed somewhat with Shea, for in a footnote he says: “Lake George, according to Jogues, was called by the Mohawks Andiatarocte, or ‘Place where the Lake closes.’ Andiataraque is found on a map of Sanson. Spafford, ‘Gazetteer of New York,’ article ‘Lake George,’ says that it was called Canideri-oit, or ‘Tail of the Lake.’ Father Martin, in his notes on Bressani, prefixes to this name that of ‘Horicon,’ but gives no original authority. I have seen an old Latin map on which the name ‘Horiconi’ is set down as belonging to a neighboring tribe. This seems to be only a misprint for ‘Horicoui,’ that is ‘Irocoui,’ or ‘Iroquois.’ In an old English map, prefixed to the rare tract, A Treatise of New England, the ‘Lake of Hierocoyes’ is laid down. The name ‘Horicon,’ as used by Cooper in his ‘Last of the Mohicans,’ seems to have no sufficient historical foundation. In 1646, the lake, as we shall see, was named ‘Lac St. Sacrement.’” 38

The name “Horican” disappears, so far as the writer has been able to discover, from the English maps of the eighteenth century, thereby leading to the supposition that the tribe was either amalgamated or absorbed by neighboring tribes, or had been conquered and made tributary in the numerous petty Indian wars in the latter part of the seventeenth and earlier part of the eighteenth centuries. In his earlier work, “The Indian Tribes of Hudson’s River,” E. M. Ruttenber places the Horicans at the headwaters of the Hudson. He, however, changed his views in regard to the tribe considerably when he prepared his “Indian Geographical Names,” published by this association in 1906. 39 at this time he wrote: Horikans was written by DeLaet, in 1625, as the name of an Indian tribe living at the headwaters of the Connecticut. On an ancient map Horicans is written in lat. 41, east of the Narragansetts on the coast of New England. In the same latitude Moricans is written west of the Connecticut, and Horikans on the upper Connecticut in latitude 42. Morhicans is the form on Carte Figurative of 1614-16. and Mahicans by the Dutch on the Hudson. The several forms indicate that the tribe was the Moricans or Mourigans of the French, the Maikans or Mahikans of the Dutch and the Mohegans of the English. It is certain that that tribe held the headwaters of the Connecticut as well as of the Hudson. The novelist, Cooper, gave life to DeLaet’s orthography in his ‘Last of the Mohegans.’”

I may say, however, that I believe Ruttenber was mistaken as to the dominancy of the Mohicans at the headwaters of the Hudson, unless this tribe can be connected with the Adirondacks who were the claimants of that entire region. At any rate Doctor Beauchamp 41 in his “Aboriginal Occupation of New York” gives the region between Troy and Saratoga as the northernmost habitation of the Mohicans.

From the writer’s studies and investigations then he is convinced that at no time was there such a tribe as the “Horicans” near Lake George, and that Cooper’s own admission of no scientific basis for the name in his preface of 1851 would have settled the matter beyond a doubt except for Miss Cooper’s attempt to support her father’s work by claiming a sort of authority for its local use.

The writer is inclined to think, on the evidence of early sources, that the name “Horican” is a corruption of the word, Mohican.

Most of this statement may be considered a work of supererogation; but, when we find the name used for Lake George by others, who should have been informed, and even appearing in works issued by the Government of the United States as standard as applicable to that region, this protest against its authenticity we believe well justified, in this connection.

After a delightful visit to Lake George, Ticonderoga and points on Lake Champlain, Cooper and his party retraced their steps to Glens Falls, the fame of whose cataract was, and has been to the present time, more than local.

They crossed the old bridge and climbed down upon the island to see the wave and weather-worn recesses in the rocks, and view, near at hand, the waters tumbling into “the gulf” above. Family tradition had it that the future Lord Derby told Cooper “here was the very scene for a romance,” and the author promised his friend that a book should be written in which these caves would play an important part. 41

How well the promise was carried out, those who read the book can tell. 42 Cooper has handled his material with skill and considerable fidelity, and has affixed to the river at Glens Falls and the cave an undying fame, so that for nearly a century it has been a visiting place for European and American travelers. for scientist and layman, for geologist and artist, for seekers after the unusual and those who care for the scenic changes.

This brings us perhaps by a devious route, to the fictitious use made of Colonel Munro in Cooper’s novel and to the bestowment upon him, by two separate marriages, of the two famous heroines of the novel, Cora and Alice, the beautiful and attractive half sisters, the sad fate of one of whom throws the doom of tragedy over the closing pages, and adds the touch of human interest to the pen pictured stories of Cora and Uncas, the Last of the Mohicans. We remember that Cooper made Lieutenant Colonel Munro an old and service-worn officer, rugged of fame, and stalwart in character, called by the Indiana “Grey-head.” 43 I imagine these are but adroit touches of the novelist to add vraisemblance to his tale.

It was the good fortune of the writer of this article to add to history, even though it be a minor service, the true facts and lineage of Lieutenant Colonel Munro, through correspondence with John A. Inglis of Edinburgh, an advocate of the Scottish bar, and an able genealogist and historian, who in his study of the Munro family discovered and sent to me the facts I published in the Proceedings of the Association in 1914, 44 which readers of this sketch should consult in connection with it. Goldsbrow Banyer, deputy secretary of the province, in his diary under date of Wednesday, August 17, 1757, wrote: “Two officers came in [to Albany] this Morning from Fort Edward. They say ... that Col. Munro was coming with his one piece of cannon he brought from W. H. 45 [William Henry].”

Colonel Munro must have come to Albany in late August or early September. Evidently he brooded on his sorrows and lack of governmental support till both took their toll of body and mind.

In the Inglis-Holden correspondence herein alluded to attention was called to an entry in the diary of the Rev. John Ogilvie, missionary and rector of the English church (now St. Peters) in Albany, which is in the State Historian’s custody. There in the year 1757, the reverend rector wrote: “Nov. 3d This morning Lieut. Col. Munro of ye 35ᵗʰ Regt. departed this life very suddenly.” 46 From a footnote to a colonial soldier’s diary, we learn his death was attributed to apoplexy and that he died on the street. 47 Continuing, the Ogilvie diary says, “Nov. 4, 1757, This day Lieut. Col. Munro was decently buried in ye church.”

Albany was full of colonial and British officers and soldiers just then, and we may suppose the stricken man was given the last ceremonies with all the pomp and circumstance his rank demanded. January 1, 1758, a commission of colonel was issued to him, but at that time the news of his death apparently had not reached England, for he was entered through some mistake in the “Army lists,” printed later, as having died in February 1758. The Ogilvie diary, however, is unquestionably an authentic instrument, so we must decide that the army lists were wrong as to the date of his death, and the footnote in some of the editions to the “Last of the Mohicans” erroneous in this regard. 48 After volume 13 of the Historical Association Proceedings had been printed and distributed, the writer received a letter from Mr. Inglis, the Edinburgh advocate heretofore mentioned, who had continued his investigations into the family of Colonel Munro, which seemed to him to be purely fiction and added by Cooper through the necessities of the story. The discovery which Mr. Inglis finally made, which not only proved his theory, but forever settles the question relating to Cora and Alice as real personages in a historic novel, is given in his letter which follows:

13 Randolph Crescent Edinburgh 22ⁿᵈ Dec. 1915

Dear Sir,

I have not heard yet whether the article on Colonel Monro has been published and the following scrap of information about him may be in time.

I find that his will was proved in 1759 in the Prerogative Court of Ireland. He had only about £200 to dispose of, and he left it to three “reputed” children, all minors.

Consequently the two daughters, children of different marriages, who figure so largely in “The Last of the Mohicans,” are, as I suspected, an effort of Cooper’s imagination.

The will was made in Dublin on 7ᵗʰ February, 1756, just before his regiment left for foreign service. 49

Yours sincerely,

(Signed) John A. Inglis.

Just what the “reputed” children allusion means, we can not now, with the present evidence before us, say. It is possibly a legal term of those days. At any rate, such children as he had he evidently desired to provide for, before he left for the dangers of America, and his children, being minors, were evidently left behind, to be cared f some unknown person or persons, when his will with its little estate of a thousand dollars or less was finally probated. His home must have been in Ireland rather than Scotland at the time, although his nationality was Scotch according to Mr. Inglis’ investigation.

To the casual reader it will not matter whether Colonel Munro was married once or twice or not at all, whether he had children or not, or whether Cooper has furnished him with a ready-made but interesting family, but to the historian it is of moment that in dry and dusty legal files, long hidden from human sight, should be found one hundred fifty-eight years after the period depicted by the novelist so entertainingly and so convincingly, the evidence that Munro, like other men, had had his romance, had reared a real family and tried to provide for it. All this, too, before coming to the land where he was to lose his life, principally through the lack of courage, the pusillanimous character, of the general whom Sir William Johnson characterized “as the only Englishman he ever knew who was a coward.”

Probably st that time it was farthest from Munro’s thoughts that he, a humble lieutenant colonel of his majesty’s forces, was to be longer remembered than almost any other officer who came across the seas to fight for the integrity of the colonies. That too, not through the medium of sober and matter-of-fact history, full of romance and of interest as the tales of those days are, and have been made to appear by Bancroft, Parkman and others, but chiefly through the efforts of a New York State fiction-writer, to adorn a tale and furnish material for a story which bids fair to live forever, and so eternally perpetuate his memory.

With the siege of Fort William Henry, historically considered, it is not needful to take up space in this article. Cooper’s description is near enough for fictional purposes, while those who would follow the fortunes of that despicable and disgraceful campaign of the English leaders can find an accurate account in the writings of the historians of that unlucky period of English and American history. 51

“COOPER’S CAVE” AND “THE FALLS”

Even before the falls and the cave were immortalized by Cooper, they had been noted; and for the sake of comparison, and at the risk of going afield from the original subject, I have chosen these extracts from the writings of the persons who had traveled far to see them, and to observe them in their details.

.

Cooper’s Cave, Glens Falls (When he saw it, 1824, the upper cleft was solid rock.) Photo by O.A. Brower, 1917.

The first of these in point of time, though not perhaps in publication, is that given by the “Sexagenary,” whose father was one of the teamsters employed by Colonel, afterwards General, Henry Knox to bring down to Albany in the winter of 1775-76 the cannon captured at Ticonderoga, which later did good service for the American forces on Dorchester Heights. The “Sexagenary” says: “The cannon captured from the enemy, were next to be brought down from the north, and as many as one hundred and twenty, besides howitzers and swivels, had fallen into our hands, with the two fortresses, Ticonderoga and Crown Point, before mentioned. They had been in part removed to the head of Lake George, and thither we were directed to proceed for them. Colonel Knox, afterwards the able chief of our artillery, undertook to superintend their removal in person. He had very heavy sleds prepared for the occasion, and a numerous train set out from our neighborhood to bring down the cannon. We reached Glen’s Falls the first night, even then celebrated as an object of curiosity.” 51

In 1776, Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Chase and Charles Carroll of Carrollton made their way to Canada as commissioners to secure the cooperation of the Canadians in the struggle for American independence. They passed through Lake George, stopping at Glens Falls on the way. Mr. Carroll in his journal thus describes them:

“(April) 17ᵗʰ, (1776) Having breakfasted with Colonel Allen, we set off from Fort Edward on our way to Fort George. We had not got a mile from the fort when messenger from General Schuyler met us. He was sent with a letter by the general to inform us that Lake George was not open, and to desire us to remain at an inn kept by one Wing at seven miles distance from Fort Edward and as many from Fort George. The country between Wing’s tavern and Fort Edward is very sandy and somewhat hilly. The principal wood is pine. At Fort Edward the river Hudson makes a sudden turn to the westward; it soon again resumes its former north course, for, at a small distance, we found it on our left and parallel with the road which we travelled, and which, from Fort Edward to Fort George, lies nearly north and south. At three miles, or thereabouts, from Fort Edward, is a remarkable fall in the river. We could see it from the road, but not so as to form any judgment of its height. We were informed that it was upwards of thirty feet, and is called the Kingsbury falls. We could distinctly see the spray arising like a vapor or fog from the violence of the falls. The banks of the river, above and below these falls for a mile or two, are remarkably steep and high, and appear to be formed or faced, with a kind of stone very much resembling slate. The banks of the Mohawk’s river at the Cohooes are faced with the same sort of stone; it is said to be an indication of sea-coal. Mr. Wing’s tavern is in the township of Queensbury, and Charlotte county; Hudson’s river is not above a quarter of a mile from his house. There is a most beautiful fall in the river at this place. From still water, to the foot of the fall, I imagine the fall cannot be less than sixty feet, 52 but the fall is not perpendicular; it may be about a hundred and twenty or a hundred and fifty feet long, and in this length, it is broken into three distinct falls, one of which may be twenty-five feet nearly perpendicular. I saw Mr. Wing’s patent — the reserved quit-rent is two shilling and sixpence sterling per hundred acres; but he informs me it has never been yet collected.” 53

In the winter of 1780 the Marquis de Chastellux, a French major general under Rochambeau and a writer of note in his day, visited the northern part of New York. He had letters to General Schuyler, who received him most hospitably. Concerning his trip he writes: 54

“Dec. 29-30, 1780.

General Schuyler ... gave us instructions for our next day’s expedition as well to Fort Edward as to the cataract of Hudson’s river. Eight miles above that fort and ten from Lake George. ...

“As you approach Fort Edward the houses become more rare. This fort is built fifteen miles from Saratoga, in a little valley near the river, on the only spot which is not covered with wood, and where you can have a prospect to the distance of a musket-shot around you. Formerly it consisted of a square fortified by two bastions on the east side, and by two demi-bastions on the side of the river; but this old fortification is abandoned, because it was too much commanded, and a large redoubt, with a simple parapet and wretched palisade, is built on a more elevated spot: within are small barracks for about two hundred soldiers. Such is Fort Edward, so much spoken of in Europe, although it could in no time have been able to resist five hundred men, with four pieces of cannon. I stopped here an hour to refresh my horses, and about noon set off to proceed as far as the cataract, which is eight miles beyond it. On leaving the valley, and pursuing the road to Lake George, is a tolerable military position, which was occupied in the war before the last: it is a sort of entrenched camp, adapted to abattis, guarding the passage from the woods, and commanding the valley.

“I had scarcely lost sight of Fort Edward, before the spectacle of devastation presented itself to my eyes, and continued to distress them as far as the place I stopped at. Peace and industry had conducted cultivators amidst these ancient forests, men content and happy, before the period of this war. Those who were in Burgoyne’s way alone experienced the horrors of his expedition; but on the last invasion of the savages, the desolation has spread from Fort Schuyler (or Fort Stanwix), even to Fort Edward; I beheld nothing around me but the remains of conflagrations; a few bricks, proof against the fire, were the only indications of ruined houses; whilst the fences still entire, and cleared out lands, announced that these deplorable habitations had once been the abode of riches, and of happiness. Arrived at the height of the cataract it was necessary to quit our sledges, and walk half a mile to the bank of the river. The snow was fifteen inches deep, which rendered this walk rather difficult, and obliged us to proceed in Indian files, in order to make a path. Each of us put ourselves alternately at the head of this little column, as the wild geese relieve each other to occupy the summit of the angle they form in their flight. But had our march been still more difficult, the sight of the cataract was an ample recompense. It is not a sheet of water as at Cohoes, and at Totohaw; the river confined, and interrupted in its course by different rocks, glides through the midst of them, and precipitating itself obliquely forms several cascades. That of Cohoes is more majestic, this more terrible; the Mohawk river seems to fall from its own dead weight; that of the Hudson frets, and becomes enraged, it foams and forms whirlpools, and flies like a serpent making its escape, still continuing its menace by horrible hissings.

“It was near two when we regained our sledges, having two and twenty miles to return to Saratoga, so that we trod back our steps as fast as possible; but we still had to halt at Fort Edward to refresh our horses. We employed this time, as we had done in the morning in warming ourselves by the fire of the officers who command the garrison. They are five in number, and have about one hundred and fifty soldiers. They are stationed in this desert for the whole winter, and I leave the reader to imagine whether this garrison be much more gay than those of Gravelines, or Briancon.” 55

Soon after the Revolution the settlers of Queensbury again took up their labors, building anew their homes and mills and industries destroyed in the struggle for liberty. The Rev. Timothy Dwight, president of Yale College, in search of health journeyed through New England and New York and came to Glens Falls in the fall of 1798. Doctor Dwight says:

“Thursday, October 4ᵗʰ, [1798] we left Sandy-Hill; and rode two miles and a half up the Hudson, to see the cataract called from a respectable man, living in the neighborhood, Glen’s Falls. The road to this spot passes along the north bank of the river.

“The rock over which the Hudson descends at this place, is a vast mass of blue limestone, horizontally stratified; and, I believe, exactly resembling that, which produces the falls of Niagara. How far this stratum extends northward and westward, I am ignorant. Down the river it reaches certainly as far as Fort Edward.

“The river at this place runs due east; and is forty rods in breadth. Almost immediately above the cataract is erected a dam, eight or ten feet in height, for the accommodation of a long train of mills on the north, and a small number on the south bank. Below the dam the limestone extends, perhaps thirty or forty rods down the middle of the stream; leaving a channel on each side. That on the north is about one third of the breadth of the river. That on the south, where narrowest, is perhaps a tenth; and, where widest is divided into two by another part of the rock. The breadth of both, taken together, is not far from that of the north channel.

“The part of this rock, which is nearest to the dam, is washed by the stream; and its surface is wrought everywhere into small figures, resembling shells. A short distance below the dam, it is covered with earth for about twelve or fifteen rods each way; and, to a considerable extent, with pines and underwood. Below the road, which between the bridges crosses this ground, the rock is divided into two arms; with a deep channel between them hollowed out by the stream, and by the weather. One bridge crosses the north channel; and two, the south; in a direction from north-west to south-east.

“The perpendicular descent of the water at this place is seventy feet. The forms, in which it descends, are various beyond those of any other cataract within my knowledge. All the conceivable gradations of falling water from the mighty torrent to the showery jet d’eau, are here united in a wonderful and fascinating combination. In the channel on the north side, twenty rods in breadth near the dam, and about twelve at the bridge, the greatest mass of water descends in four principal streams, divided by three huge prominences of the rock, and in several smaller ones. The prevailing appearance here is that of sublimity, as the river descends either in great sheets, or violent torrents. There are, however, several fine cascades in this compartment; and the effect of the whole is not a little increased by innumerable streams, torrents, and jets, from the long succession of mills on the north shore.

“The southern division of this scene is, however, a still finer object than the northern. On the north side of this channel the river has worn a ragged, perpendicular chasm through the rock, about thirty feet in breadth, eight or ten rods in length, and fifty or sixty feet in depth. Through this opening pours a single torrent in a mass of foam; and is joined by ten or twelve currents, rushing from the southern side with every wild variety of form, and with a beauty, and magnificence, incapable of being described.

“On the eastern part of the island, below the road, the water has worn three passages beneath the surface quite through the rocky points, which border the channel, mentioned above: two, through the northern arm of the island; and one, through the southern. These passages are about three rods in length; and sufficiently wide, and high, for a man to pass conveniently through them. The surface of the reek, above them, is smooth, and entire. I was at a loss to conceive what cause has produced these passages; as their direction was exactly at right- angles with the current. In the year 1802, when I visited the falls the third time, I found a fourth passage cut through one of the same arms, in all respects similar to those I have mentioned. If it existed at all in the rear 1798, it was so small that it was not only unobserved by us, but had never been discovered by any of the neighbouring inhabitants. So remarkable a fact induced me to search for the cause; and I soon became satisfied. This stratum of limestone, by means of its numerous crevices, is almost everywhere pervious to the water; and is of such a texture as to be easily and rapidly worn away by its force. When a cold season succeeds a freshet, a stone, wherever it happens to be wet, is broken by the frost; and, as it is evident from the numerous square blocks, here, and throughout this vicinity, into which it has been fashioned by the same cause, is prone to crack perpendicularly to the surface of the strata. Wherever there is a fissure, the water pours through it; and by the force of the current, and the aid of continual frosts, a chasm is soon formed, of considerable extent.

“In this manner the whole channel of the Hudson at this place has been hollowed out. Originally these falls were in the neighbourhood of Fort Edward: five miles below their present station. During a long succession of ages, the river has gradually worn this deep channel backward to this place. Among other proofs of the facts here asserted, this is one. In the year 1799, I visited this spot the second time; and with a good deal of care drew outlines of every thing material, relative to their figure and appearance. In my third visit, three years afterwards, I found them so much altered that the resemblance was in a considerable measure lost. The great features were the same: but the smaller ones were, even in this little period, essentially changed. What, then, must have been the efficacy of these powerful agents, during more than forty centuries.

“The shores of the river, below the falls are wrought, so far as they are in sight, into many forms; smooth, rough, convex, concave, perpendicular, overhanging and generally very irregular in their appearance.

“The whole effect of this scene may be arranged under the heads of grandeur, variety;, wilderness, and beauty. The grandeur arises from the height, perpendicularity, and raggedness, everywhere seen, of this immense mass of rock; and from the dimensions and force of the torrent. The wildness is extreme, the variety endless, and the beauty intense. From some pictures, which I have seen, I should believe Salvator Rosa might have exhibited this group of objects with advantage; but it would demand the whole power of his pencil.” 56

An early description of the place is given in a series of articles entitled “Recollections:” numbers one, two and three, over the signature of “Harlow,” published in the Warren Messenger of Glens Falls, February 5, 12 and 19, 1831, in which the writer says:

“The village of Glen’s Falls was formerly known by the name of Wing’s Falls, a name probably derived from Mr. Abraham Wing. one of the first emigrants to this place, who lived in a log building which occupied the spot of Mr. L.L. Pixley’s store. ...

“Then followed the dams, the one above, and the other below the falls, and the mill seats afforded by them, owned and occupied by Mr. Benjamin Wing, and Gen. (Warren) Ferriss. Only one of these dams is still remaining — that at the head of the rapids, now a bank of five feet high, and about 600 broad, over which the river pours its waters in one unbroken sheet. ... An Indian, for a trifling reward, paddled his canoe to the brink of the precipice, and then shot like lightning into the gulf to disappear forever, and the same is related of many others who dared the fury of the cataract.

“But it is safe to leap from any of the rocks, at the southern point of the island or as far west as the bridge. This was fully attested by Cook, who jumped three successive times from the old king-post, into the water beneath (the gulf at the foot of the arch), and returned, exclaiming like Patch ‘there’s no mistake.’” 57

Doctor Dwight made at least four visits to Glens Falls, the fourth in 1811, when he wrote:

“Monday, October 23d [1811] 58 accompanied by Mr. L------ we rode to Stillwater; and, after being obliged to wait three hours for our dinner, proceeded to Argyle on the eastern side of Miller’s falls. Mr. L. left us the next morning; and we proceeded to Lake George; passing through the villages of Fort Edward, Sandy Hill, and Glen’s Falls. Here we dined; and, while our dinner was preparing, went down to examine this noble cataract. To my great mortification I found it encumbered and defaced, by the erection of several paltry building, raised up since my last visit to this place. The rocks, both above and below the bridge, were extremely altered, and greatly for the worse, by the operations of the water, and the weather. The courses of the currents had undergone, in many places, a similar variation. The view, at the time, was broken by the buildings: two or three of which, designed to be mills, were given up as useless, and were in ruins. Another was a wretched looking cottage; standing upon the island between the bridges. Nothing could be more dissonant from the splendour of this scene; and hardly any thing more disgusting. I found a considerable part of the rocks, below the road, so much wasted, that I could scarcely acknowledge them to be the same.” 59

In the first state gazetteer it was of course natural to notice Glens Falls. The work states:

“Glens Falls, on the Hudson, three miles west of Sandy-Hill, form a pleasing group of picturesque scenery. The whole descent is about 35 feet, or 28 within three rods, and the whole waters of the Hudson fall in beautiful cascades over a rock of very fine primitive limestone. The physiognomy of this country, and its geologic features are singular and highly interesting. A dam of about four feet has been erected across the river at the head of the falls, over which the water falls in one sheet, and is immediately separated by the rocks, into four principal channels, rushing down their respective cataracts with inconceivable force; nor do they all unite for some distance. Through the rocks that form these islands, are some long excavations or caverns, presenting arched subterranean passages of considerable extent, evidently worn by the water; as a lateral seam, common in limestone rocks, formed a conducting medium, and may be still traced beyond the excavations. On one of the islands stand a carding-machine and old sawmill, and a toll-bridge extends across the river immediately below the falls, which rents for $600 a year. This island is in the Town of Moreau, but the main stream is in Queensbury. On each shore are mills, the water being conveyed in short canals or flumes from the dam.” 61

In the autumn of 1819, Dr. Benjamin Silliman, the distinguished professor of science at Yale College, made his journey from Hartford to Quebec, and, stopping at Glens Falls, he described it as follows:

“We stopped for a few moments at this celebrated place. It is not possible that so large a river as the Hudson is, even here, at more than two hundred miles from its mouth, should be precipitated over any declivity, however moderate, without a degree of grandeur. Even the various rapids which we had passed above Albany, and still more, the falls at Fort Miller Bridge, and Baker’s Falls, at Sandy Hill, had powerfully arrested our attention, and prepared us for the magnificent spectacle now before us. I regretted that I could not, more at leisure, investigate the geology of this pass, both for its own sake, and for its connexion with this fine piece of scenery.

“The basis of the country here is a black limestone, compact, but presenting spots that are crystallized, and interspersed, here and there, with the organized remains of animals entombed, in ages past, in this mausoleum. The strata are perfectly flat, and are piled upon one another, with the utmost regularity, so that a section, perpendicular to the strata, presents almost the exact arrangement of hewn stones in a building. Such a section has been made by the Hudson, through these calcareous strata; not however all at once; a number of layers are removed, either through a part of the width of the river, or through the whole of it; and, a few feet further down the stream, the layers, next below are removed; and thus, by stairs, or rather broad platforms, not however without frequent irregularities, and deep channels cut by the water in the direction of the river, the way is prepared for this fine cataract.

“Down these platforms, and through these channels, the Hudson, when the river is full, indignantly rushes, in one broad expense; now, in several subordinate rivers, thundering and foaming among the black rocks, and at last dashing their conflicting waters into one tumultuous raging torrent, white as the ridge of the tempest wave, shrouded with spray, and adorned with the hues of the rainbow. Such is the view from the bridge immediately at the top of the falls, and it is finely contrasted with the solemn grandeur of the sable ledges below, which tower to a great height above the stream.

“I do not know the entire fall of the river here, but should think, judging from the eye, that it could not be less then fifty feet, 61 including all its leaps, down the different platforms of rock.

“Through an uninteresting country, partly of pine barren, and partly of stony hills, I arrived at nightfall, at the head of Lake George, and found a comfortable inn, in the village of Caldwell, on the western shore.” 62

In the second edition of Spafford’s Gazetteer, the editor has added somewhat to his former data. He writes:

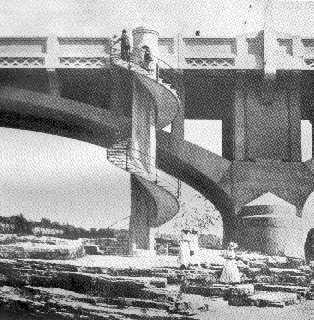

Glens Falls toll bridge and flat rock (as seen by Cooper in 1824). Hudson River Portfolio, 1824. St. Louis Art Museum.

“The Post-Village of Glen’s Falls, 63 situated at the falls, on the north bank of the Hudson, on a fine plain, is a pleasant busy little place, three miles west of Sandy-Hill, having a church, schoolhouse, several mills, a toll-bridge, and a handsome collection of about 100 houses, stores, etc. About three miles north, at a place called the Ridge, there is a little village of some 20 houses; and at five miles, another, called Oneida; having about the same number. The road from Saratoga Springs to Lake George, leads through this town, crossing the Hudson at Glen’s Falls, a charming cataract, where the waters of that river fall over a rock of secondary limestone, in beautiful cascades. The descent is 37 feet, exclusive of a dam of five feet, immediately at the head of the falls, over which the water descends in an entire sheet, the whole width of the river. There is an island of rock just below this fall, by which the waters are separated into two channels, over which the bridge is thrown. ... In the seams of the horizontal lime rook, on the island below the falls, there are some curious excavations, water-worn, well worth a little attention from tourists.” 64

Spafford’s Gazetteerpresents the nearest description we have of the falls to the time of Cooper’s visit, and is doubly interesting on that account.

The next nearest account of the falls is that given by the British writer and traveler, James Stuart, who visited this region between September 15 and 20, 1828, but who in the following passage does not seem to have visited the cave or described it:

“It had been our intention to proceed southward from Ticonderoga by Lake George, but we found that the steamboat on that lake was discontinued, on account of the lateness of the season, and were therefore obliged to make a circuit by Whitehall, Sandyhill, and Glen’s Falls, four miles from Sandyhill, and situated on the Hudson, before we could get by a road to Caldwell, at the head of Lake George. We reached Glen’s Falls, in time for a late dinner, on the 18ᵗʰ September, and found Mr. Threehouse’s hotel a very good one, and the host, a French Canadian. very obliging, not at all disposed to make any difficulty in getting us broiled chickens, and other good things, though a long time after the regular dinner hours. A very good female servant waited at dinner, sitting, of course, at all times when she was doing nothing for us. This practice was more observed by us, being in private rooms, which we had here, than at a table with boarders.

“The falls of the Hudson, close to this vaillage { sic}, are well worth seeing. The descent is above sixty feet, the water separating at the bottom into three channels, and dashing over great flat layers of black limestone rock. They are best seen from the pendant wooden bridge, 160 yards broad, the arches of which are supported on pillars, consisting of large beams laid across each other, resting on a foundation of limestone, cut through by the Hudson. The village is clean, containing probably 1000 people. The district of country is reckoned very cheap. Boarding for mechanics or labourers at a dollar and a half per week; and for this sum animal food allowed three times a day.” 65

One of the earliest of New York State guidebooks was that of C. M. Davison of Saratoga Springs, which ran through a number of editions before the fifties of the nineteenth century, the earliest of which in the writer’s possession is that of 1828. Davison’s account for the 1840 edition in the New York State Library, is as follows:

“Glen’s Falls, a village more populous, [than Sandy Hill] is three miles further up the Hudson river, on the direct route to Lake George. At this place are the celebrated falls from which the village takes its name. These are situated about one fourth of a mile south of the village, near a bridge, extending partly over the falls, and from which the best view of them may be had. The falls are formed by the waters of the Hudson, which flow in one sheet over the brink of the precipice, but are immediately divided by the rocks into three channels. The height of the falls is ascertained, by measurement, to be 63 feet; though the water flows in an angular descent of 4 or 500 feet. Some rods below the falls is a long cave in the rocks, extending from one channel to the other. On its walls are inscribed a variety of names of former guests, who have thought proper to pay this customary tribute. The rocks, which are at some seasons covered with water, but at others entirely dry, are checquered with small indentations, and in many places considerable chasms are formed, probably by pebbles kept in motion by the falling water. It is very evident that these falls, like those of Niagara, were once a considerable distance lower down the river — the banks below being composed of shelving rocks, from 30 to 70 feet perpendicular height. On the north side of the river is a navigable feeder, communicating with the Champlain canal. It commences nearly two miles above the Falls, and, with the exception of about a quarter of a mile, which appears to have been cut out of a shelving rock, runs along a ravine east of Sandy Hill, and intersects the main canal some distance below.

“There are extensive quarries of black and variegated marble at Glen’s Falls, which is here sawed into slabs and transported to New York for manufacture.

“From Glen’s Falls to Lake George the distance is nine miles over an indifferent road, affording little other variety than mountains and forests, with here and there a rustic hamlet. Within three and a half miles of Lake George on the right hand, and a short distance from the road, is pointed out the rock at the foot of which Colonel Williams was massacred by the Indians, during the French war. At the distance of half a mile farther, on the same side of the road, is the “Bloody Pond,” so called from its waters having been crimsoned with the blood of the slain who fell in its vicinity, during a severe engagement in 1755. Three miles farther is situated the village of Caldwell.” 66

This series of extracts may fittingly he closed by the description given by the great historian of the French and Indian Wars, Francis Parkman, in his diary for 1842, describing his trip from Boston, through Lakes George and Champlain, published a few years ago in Scribner’s Magazine. He says:

“July 16ᵗʰ. [18421 Caldwell — This morning we left Albany — which I devoutly hope I may never see again — in the cars for Saratoga. My plan of going up the river to Fort Edward I had to abandon, for it was impracticable — no boat beyond Troy. Railroad the worst I was ever on; the country flat and dull; the weather dismal. The Catskills appeared in the distance. After passing the inclined plane and riding a couple of hours, we reached the valley of the Mohawk and Schenectady. I was prepared for something filthy in the last-mentioned, venerable town, but for nothing quite so disgusting as reality. Canal docks; full of stinking water, superannuated, rotten canal-boats, and dirty children and pigs paddling about, formed the delicious picture, while in the rear was a mass of tumbling houses and sheds, bursting open in all directions; green with antiquity, dampness, and lack of paint. Each house had its peculiar dunghill, with the group of reposing hogs. In short, London itself could exhibit nothing much nastier. In crossing the main street, indeed, things wore an appearance which might be called decent. The car-house here is enormous. Five or six trains were on the point of starting for the North, South, East, and West; and the brood of rail-roads and taverns swarmed about the place like bees. We cleared the babel at last, passed Union College, another tract of monotonous country, Bal{l}ston, and finally reached Saratoga, having travelled latterly at the astonishing rate of seven miles an hour. “Caldwell stage ready.” We got our baggage on board, and I found time to enter one or two of the huge hotels. after perambulating the entries, filled with sleek waiters and sneaking fops, dashing through the columned porticos and enclosures, drinking some of the water and spitting it out again in high disgust, I sprang onto the stage, cursing Saratoga and all New York. With an unmitigated temper, I journeyed to Glens Falls, and here my wrath mounted higher yet at the sight of that noble cataract almost concealed under a huge, awkward bridge, thrown directly across it, with the addition of a dam above, and about twenty mills of various kinds. Add to all, that the current was choked by masses of drift logs above and below, and that a dirty village lined the banks of the river on both sides, and some idea may possibly be formed of the way in which the New Yorkers have be-devilled Glens. Still the water comes down over the marble ledges in foam and fury, and the roar completely drowns the clatter of the machinery. I left the stage and ran down to the bed of the river, to the rocks at the foot of the falls. Two little boys volunteered to show me the “caverns,” which may be reached dry-shod when the stream is low. I followed them down, amid the din and spray, to a little hole in the rock, which led to a place a good deal like the “Swallow’s Cave,” and squeezed in after them. “This is Cooper’s Cave, sir; where he went and hid the two ladies.” They evidently took the story in “The Last of the Mohicans” for gospel. They led the way to the larger cave, and one of them ran down to the edge of the water, which boiled most savagely past the opening. “This is Hawley’s Cave: here’s where he shot an Indian.” “No, he didn’t either,” squalled the other, “it was higher up on the rocks.” “I tell you it wasn’t.” “I tell you it was.” I put an end to the controversy with two cents.

“Dined at the tavern and rode on.” 67

By comparing these actual earlier descriptions of the river and falls and caves at Glens Falls, with the pen picture of Cooper in his novel, the reader will gain a good idea of the skill he has used in restoring to a state of primitive being the region of northern New York, and the location of the falls. He has, however, as stated in the beginning, erroneously given them the name of “Glenn’s” to which, as shown, the falls were not entitled until nearly forty years later. In fact, in an old map upon which the Queen Ann patent of the Kayaderosseras is based in 1708, what is now Hudson Falls is marked as “3 Falls” and Glens Falls as “4ᵗʰ Falls.”

On the Alexander Colden survey of the John Glen patent, dated January 14, 1771, which included the present South Glens Falls, the waterfall at Hudson Falls is shown as “Third Falls,” but, strangely enough, “Glens Falls,” as the place was later to be called, are not shown. 68

The writer was, as already stated, born within the sound of the falls, and so has always been familiar with the cave and its surroundings. Usually, during the spring and fall rains, the falls come down in spate, their full flood covering the rocks and, with a thunderous foamy mass, filling the gulf below. Then the “flat rock,” as it has been called ever since I first knew the spot, is covered with the rushing waters, and the cave forms a raceway through which the waters rush from one side to the other.

For many years it has been the hope of conservationists so to arrange our water supply as to keep an even flow of water in the upper region of the Hudson and its tributaries. These authorities are disposed to call attention to the bare rocks and ledges at Glens Falls as evidence of the lack of flowage which should be corrected. For nearly 50 years, however, the writer has been familiar with the local cry of low water, when mills must shut down and local industries must be curtailed.

It was this regularity of condition which led to the starting of the local shirt and collar industry in 1876, which in the end placed Glens Falls among the leading manufacturing cities in the country in this line, while the lime and lumber trade of the old days diminished and grew smaller and smaller.

Cooper saw the cave when it was out of water and during the low-water period. And his novel, fortunately for his purposes, starts at the period of the year when the cave would have been available for use as a hiding place.

In this connection it may be of interest to consider how during the years the flat rock and the caves were approached from the banks by travelers on either side, it being remembered that the cave is in what is known as “the island,” separated on each side by the north and south channels of the river, which here is practically the narrowest part of the Hudson, pent between its rocky banks of black marble.

Just what means were employed to cross the river after the settlement in 1766, and the erection of Wing’s mills at the falls, is unknown. there was possibly some kind of bridge, and perhaps a ferry somewhere close by, although it is known that a rough ford existed, still to be seen in low water, starting back of the old Transportation Company’s building on Canal street, and coming out near the paper mill below the fiat rock, opposite the lower point of the island. 69

It is possible too that there was some kind of rough bridge in Revolutionary times, for it has been stated that a fort stood on the Moreau side of the river, about where the lower paper mill now is, at the time of the Burgoyne invasion.

Doctor Holden says: “In the Warren Messenger, of February 5ᵗʰ, 12ᵗʰ and 19ᵗʰ, 1831, there were published a series of articles entitled Recollections, over the signature of ‘Harlow.’

From these is extracted the following quotation:

“String pieces for crossing the Hudson at our village, were constructed in 1786, which extended from the island to either shore. These endured about three years, when the present bridge, and toll-house were built. ... The mole at the Sand beach with the mills it supported, was carried away in a freshet, and few traces of its original situation can at this time be discovered.” 71

The town records of Queensbury also show that in 1798 John A. Ferriss was allowed eight dollars and fifty cents for services on the river bridge, proving its existence then, and confirming the foregoing, although “Harlow” was mistaken as to the date of the erection of the toll-bridge.

In 1802 Warren Ferriss, a prominent mill owner and citizen of Glens Falls, secured a grant from the Legislature of the State of New Pork through an act passed April 2, 1802, allowing him, his executors, administrators and assigns, to build a toll-bridge over the Hudson river at Glens Falls, which bridge was to be “not less than 16 feet wide, with a strong railing on each side thereof and built in so substantial and workmanlike manner, as that laden carriages may safely travel thereon.” The bridge was to be completed on or before January 1, 1803. 71

The following year, 1803, General Ferriss was given the right to purchase the island from the State for thirty dollars, 72 and on this, later, he erected the toll-keeper’s cottage and gate as a part of the bridge.

Several engravings of the older bridges are in existence, which we are able to show here, one of which is from the Hudson River Portfolio of views engraved by J. Hill after the paintings by W. C. Hall, 73 another from a sketch by the French artist, naturalist and traveler, Jacques Gerard Milbert who visited this country about 1817, and another front a sketch by W. H. Bartlett, the English topographical landscape painter. 74 They all show a rough sort of structure spanning the flood with the abutments resting on the fiat rock.

The rights to the toll-bridge were later acquired by the Rev. John Folsom, who succeeded Colonel John Glen as the riparian owner of the mills on the Moreau side, somewhere around 1806. 75 He built and occupied the house so long { sic}, later known as the “Rice Mansion” at the top of the hill, and now occupied by an official of the International Paper Co.

This toll-bridge, evidently the one used by Cooper and his companions at the time of his visit, and by succeeding travelers who visited the falls, up to about 1832-38, was, it appears, at that date replaced by a free bridge erected by C. P. and H. J. Cool and James Palmeter of Glens Falls, under the supervision of the town commissioners of highways. On January 25, 1833, the Warren Messenger, says: “The new free bridge across the Hudson at this place is already in a considerable state of forwardness. We understand that the constructors will commence raising it in the course of the week.” 76

The village of Glens Falls was incorporated in 1839. A notice of the application to the Legislature for an act of incorporation of the village, appeared in the Glens Falls Spectatorof December 8, 1838. In the same issue appeared a notice of a proposed application to the Legislature for a franchise for a toll-bridge. Nothing came of this, however, and in January 1839 a, notice was published, signed by leading citizens of Glens Falls, calling for a meeting of the board of supervisors of Warren county to levy a county tax for the purpose of “repairing the present bridge or constructing a new one across the Hudson river at this place.” 77 This agitation led finally to the joining of forces by Moreau and Queensbury for a new bridge, the State of New York lending the county of Warren from the school funds of the State, twenty-five hundred dollars to be paid in five annual installments with interest at the rate of 7 per cent a year. The act declares: “The money so loaned shall be applied to the building of a bridge across the Hudson river at Glen’s Falls, where the old bridge now stands, under the direction of the commissioners hereinafter appointed.” These commissioners were Alonzo W. Morgan, David Roberts and George G. Hawley, all prominent citizens of the town of Queensbury. 78

Thus followed the building in about 1842 of the old wooden truss covered bridge so familiar to the earlier residents of Glens Falls, Queensbury contributing about $2500 as her share. Moreau not far from this period built the approach to the bridge, leading from the island on the South Glens Falls side, a sort of stone causeway which spanned the seething waters of the gulf below, forming the famous “Arch” so called, which the Glens Falls Insurance Company used as a trade mark for so many years. In 1890 the old covered wooden bridge with its lattice work sides, was replaced by a standard open iron structure. In its erection an accident occurred, March 15, 1890, which caused the old bridge to fall into the boiling freshet below, carrying down several mechanics and killing nNelson Sansouci, a well-known young man of this place. At that time the road bed on each side was raised several feet, but the arch remained intact. About 1903, owing to the previous construction of the Hudson Valley railroad to Saratoga, which necessitated running heavy cars and loads over the stone bridgeway, the arch weakened and was condemned. The following winter and spring the Moreau authorities built an iron approach or extension to the bridge, and in doing so, changed the appearance and picturesqueness of the arch, around which for over sixty years had hung the glamor of romance and the genius of eventful enterprises, leaving there today only the spirit of the waters whose kindly influence still remains to bring wealth and prosperity to the Empire City of northern New York.