“Upside Down; or, Philosophy in Petticoats”

A Scene from James Fenimore Cooper’s only Play

Originally published in James Fenimore Cooper Society Miscellaneous Papers No. 1, January 1992.

Copyright © 1992 by James Fenimore Cooper Society.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

Introduction

On June 18, 1850, a “new comedy by James Fenimore Cooper” opened at Burton’s Chamber Street Theatre in New York City.

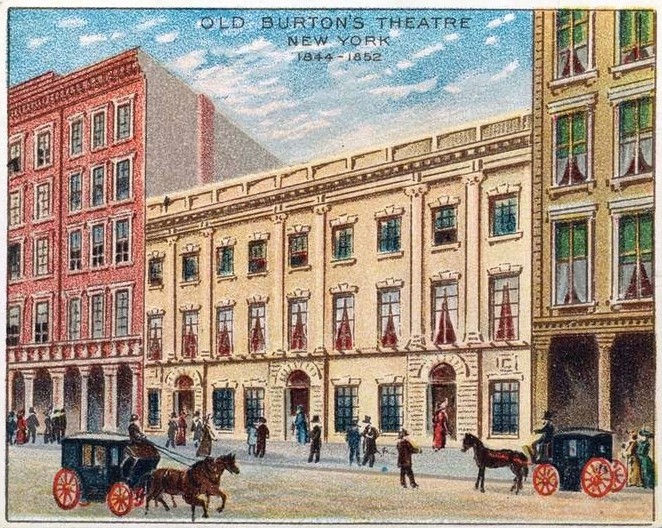

A colored lithograph from a cigarette card (c. 1910) of Old Burton’s Theatre. Public domain.

Although plays were frequently based on Cooper’s novels, Upside Down was his only personal venture into drama. The full text of Upside Down has never been found, but William E. Burton, who produced and acted the lead in its

only production, included one scene of the three-act play in his Cyclopædia of Wit and Humor Vol. I, pp. 297-299 (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1859)  This text is reproduced

here.

This text is reproduced

here.

Upside Down was not a success, and closed on June 21 after only four performances before thin houses. The New York Express said “it shows up Socialism beautifully,” and that the wooing scene was “screamingly delectable.” The Albion called it “smart, neat, and occasionally pointedly telling.” But reviewers also found the play talky and too polemical, whether on its merits or because of expectations about Cooper, whom the Albion called “The Reformer of his Age.” Cooper got $250 for his pains.

Cooper’s play was “discovered” in recent times by John Atlee Kouwenhoven, who described the play, its background and reception in “Cooper’s ‘Upside Down’ Turns Up” (The Colophon, Vol. 3 (N.S.), No. 4, Autumn 1938, pp. 525-530). Cooper listed the cast, and the Albion review summarized the plot, so that it is possible to see with some accuracy how the surviving scene fits into the lost portions of the Play. As James F. Beard noted, “the dialogue of the single scene ... is hardly Shavian,” but the play “is oddly suggestive” of George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman.

For further information on Upside Down, see Kouwenhoven’s article; James F. Beard’s discussion and relevant Cooper letters in Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960-68), Vol. VI, pp. 163-167, 197-199; and letters to Cooper in James Fenimore Cooper’s [grandson] Correspondence of James Fenimore Cooper (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1922), Vol. II, pp. 681-684.

But on with the play!

The Cast (as described by Cooper)

- Richard Lovel — “a rich old bachelor of 66”

- Francis (Frank) Lovel — his nephew, “a devotee of the new philosophy”

- Doctor McSocial — “an adventurer who sets up for a philosopher”

- Gullet, Crochet, and Rush — three of McSocial’s students

- Cato — an old black servant of Richard Lovel’s

- David — a servant of McSocial

- Sophy McSocial — the doctor’s sister

- Emily Warrington — Richard Lovel’s ward, engaged to Francis Lovel

- Dinah — Lovel’s cook and Cato’s wife

The Plot (adapted from the account in the Albion)

Frank Lovel, who is in love with his Uncle Richard’s ward Emily Warrington, is a disciple of progress and “has imbibed the communist doctrines of the day.” He has fallen under the spell of Doctor McSocial, who lectures on Socialism. Frank’s views are obnoxious to both his Uncle Richard and to Emily, but in the hope of converting him they agree to attend Doctor McSocial’s lectures. There old Lovel meets the Doctor’s young sister Sophy, who “acting upon the avowed principles of freedom and Socialism,” proposes marriage to him. Though the old bachelor is horrified, his ward Emily advises him to pretend to go along with Sophy, and he accepts her proposal. Sophy then asserts that under New York Law this makes Richard her husband, and she and Doctor McSocial move into his mansion and make his life miserable. Eventually, McSocial’s servant confesses that Sophy is really Doctor McSocial’s wife, and only pretending to be his sister. With this revelation, Richard Lovel is freed, and his nephew Frank sees the error of his ways and is accepted by Emily.

The surviving scene, from the first Act, is played between Richard Lovel, his nephew Frank, and his ward Emily Warrington.

The Text

SCENE: A Parlor. Lovel and Frank at Breakfast.

Illustration of scene from Upside Down (from Burton’s Cyclopædia of Wit and Humor).

LOVEL. I am an individual, I tell you, and not a community.

FRANK. The besetting vice of the old opinions, my dear uncle. Serious doubts are raised whether there are, properly speaking, any individuals; the great human family being composed of communities.

LOVEL. Aye, aye, just as the Menai Bridge is formed of arches.

FRANK. This is an age of movement.

LOVEL. You never said truer words, boy. New names for new ideas. Every thing in progress. Even old age keeps in motion; and I, who was sixty-six last summer, am quite likely to be sixty-seven this.

FRANK. ‘Tis the spirit of the times, sir. Progress is all in all just now.

LOVEL. Were it not for my gout —

FRANK. Neuralgia, or inflammatory rheumatism, if you please. There is no longer any gout.

LOVEL. I would be off for some other planet, and get rid of all these innovations. I hate change. There is Venus now — a very good-looking, quiet star; I think I might fancy a peaceable home under her auspices for the rest of my days.

FRANK. I am afraid, sir, it is rather late in life; and you might find the door shut in your face on your arrival, after a very fatiguing journey. Besides, the planets have their revolutions as well as opinions.

LOVEL. That’s true, by George. I did not think of that. I dare say they have their progress; their being up to the time, and all the other nonsenses of the day. You are what is called a communist, Frank.

FRANK. I reject the appellation, sir. It is true we recognize the great community principle, as opposed to a narrow, selfish, unnatural individualism; but we admit the rights of property, the relations of society, the — the — a — a — in short, all that, in justice and reason ought to be admitted. This is which distinguishes the new principles from the old.

LOVEL. Ah! I begin to comprehend — you are only an uncommon-ist!

FRANK. Well, sir, as you have promised to attend the school, I shall soon see you added to our number, let me be what I may.

LOVEL. It is useless talking, boy. If I cannot quit the earth altogether, I have discovered —

FRANK. Discovered! — what, my dear sir? — I so doat on discoveries!

LOVEL. I wonder you never discovered that you are a confounded blockhead. You doat on my ward, too; but it’s of no use; she’ll never have you. She has told me as much.

FRANK. You must excuse my saying, sir, that I think your imagination has a hand in this.

LOVEL. No such thing, sir. It appears to her to be too selfish and narrow-minded to bestow her affections on an individual, when there is a whole community to love. She has made a discovery, too.

FRANK. Of what, sir? I beg you’ll not keep me in suspense. Discoveries are my delight.

LOVEL. Suspense! — you deserve to be suspended by the neck for your foolish manner of trifling with your own happiness. Here has Emily found out that she is a social being, and she is not disposed to throw herself away on the best individual that ever lived, that’s all.

FRANK. I have unlimited confidence in the principles of Emily —

LOVEL. Her principles! — why, it is on this very community principle, as you call it, that she is for dividing up her heart into little homeopathic doses, giving a little here, and a little there, in grains and drachms, eh?

FRANK. We will not talk of Emily, sir; I would prefer to learn this discovery of yours.

LOVEL. Yes; it is a great thought in its way. I call it Perpetual Still-ism. As every thing is in motion, looking anxiously after truth, and opinions are vibrating, I have taken a central position, as respects all the great questions of the day; the human family necessarily passing me once on each oscillation. Truth is a point, and at that point I take my stand. Finding it is a wild goose chase to run after demonstration, I have become a fixture. I’m truth, and don’t mean to budge. As you are my nephew and a favorite, I’ll give you a friendly word now and then, as you swing past on the great moral pendulum of movement, coming and going.

FRANK. Thank’ee, sir; and as movement is the order of the day, I am off to McSocial’s.

LOVEL. Who is a very great scoundrel in my judgment.

FRANK. This of one of the luminaries of the times! He and his sister are blessings to all who listen to their wisdom. But I must quit you, sir. (Going.)

LOVEL. Harkee, Frank.

FRANK. Your pleasure, sir.

LOVEL. My ward won’t have you.

FRANK. May I ask why not, sir?

LOVEL. She’s converted, at last, to your opinions; regards all mankind as brothers, yourself included, and can’t think of marrying so near a relative.

FRANK. There is no community on this subject, sir. I shall continue to hope.

LOVEL. You needn’t. She has found out what a narrow sentiment it is to love an individual, I tell you, and opens her heart to the whole of the great human family.

FRANK. Love is a passion and not a principle, and I shall trust to nature. My time has come, and I must really go. I shall expect you in half an hour — six, at the latest. (Exit.)

LOVEL. This is what he calls keeping pace with the times, I suppose, and progress, and not being behind the age. Since his mind has got filled with this nonsense, I find it hard to give him any sound advice. Poor Emily is taking his folly to heart, besides being a little jealous, I fear, of this unknown sister of McSocial’s, whom she hears so much extolled. Here she comes, poor girl, looking quite serious and sad. (Enter Emily.)

EMILY. What has become of Mr. Frank Lovel, sir?

LOVEL. Off, like a new idea.

EMILY. It’s very early to leave the house — where can he have gone at this hour?

LOVEL. I heard him say he had some morning call to make.

EMILY. On whom can he call at nine o’clock?

LOVEL. The great human family. They are always in, my dear. He’ll be admitted.

EMILY. Few persons would deny themselves to Frank Lovel.

LOVEL. If they did, he would enter by the key-hole. No such thing as excluding the light.

EMILY. Why allude to him with such severity, my dear guardian?

LOVEL. Because he is a blockhead; and because he makes you sad.

EMILY. Sometimes he makes me very much the reverse. He is generally thought quite clever.

LOVEL. He’s new fangled, and that passes for cleverness with most persons. You never can marry him, Emily.

EMILY. Quite likely, sir, as I mean never to marry any one — still, I should like to know the reason why?

LOVEL. He is your brother by the great human family; and you can’t marry so near a relative. The church would not perform the ceremony over you; you come within the fifth degree. I suppose you can foresee the consequences were you to marry this vol-au-vent, Emily.

EMILY. Not exactly, sir; I suppose, should such a thing ever happen, that he would love me dearly, dearly; and that I might return the feeling as far as was proper.

LOVEL. You know that Frank is an uncommonist?

EMILY. Oh, Lord! — you quite frighten me, sir — what is that?

LOVEL. An improvement on the communist.

EMILY. I like this idea of improvement; but what is a communist?

LOVEL. A great social division, be means of which the goods and chattels of our neighbors, wives and children included, are to go share and share alike, as the lawyers say.

EMILY. All this is algebra to me.

LOVEL. It’s only arithmetic, my dear; nothing but compound division. Here am I, a bachelor, in my sixty-sixth year, happy and free. If this projects succeeds, I may wake up some morning, and find a beloved consort sharing my pillow, and six or eight turbulent members of the great human family squalling in the nursery; children whose names I never even heard — Billies, and Tommies, and Katies. I devoutly hope there won’t be any twins. They would be the death of me. I detest twins.

EMILY. But you need not marry unless you please, sir.

LOVEL. It used to be so, child; but every thing is upside down now-a-days. They may make a code to say I shall marry. You, yourself, may be enacted to marry some old fogram, just like me.

EMILY. My dear guardian! — but I would not have him.

LOVEL. Thank you, Miss Warrington. In these unsettled times one never knows what will happen. I was born an individual, have lived an individual, and did hope to die an individual; but Frank denies my identity. He says, that all individuals are exploded. Yes, Emmy, dear, I may be forced, by statute, to offer myself to you, for what I know.

EMILY. Thank you, my dearest guardian; but set your mind at rest — I’ll promise not to accept you. How can they make us marry unless we see fit? By what they call the ‘right of eminent domain,’ I suppose. They are doing all sorts of things up at Albany by means of this right.

LOVEL. That foolish fellow, Frank, is for ever chasing novelties, when Solomon himself tells us there is nothing new under the sun. He’s a very great dunce.

EMILY. In my opinion, sir, Frank knows a great deal that Solomon never dreamt of, if the truth were proclaimed. What did Solomon know of the steam engine, the magnetic telegraph, or animal magnetism?

LOVEL. And what does Frank know of the Temple, the Hebrew melodies, and the Queen of Sheba? — An ill-mannered, ill-tempered fellow, to wish to disturb elderly gentlemen in their individuality!

EMILY. Would it not be better than abusing him, sir, for you and me to pursue our scheme, by means of which Frank can be made to see the true character of these McSocials, and be brought back into his old train of opinion and feeling? As long as he thinks and acts as he does at present I am seriously resolved not to marry him — and — and — and —

LOVEL. Go on, my dear; I am all ears when a young woman is seriously resolved not to marry a handsome young fellow, whom she loves as the apple of her eye.

EMILY. I acknowledge the weakness, sir, if it be one; but am not weak enough to link my fortunes to those of a social madman, though I believe this Dr. McSocial has a notion to the contrary.

LOVEL. Whew! — the impudent rascal! — and he Frank’s bosom friend all this time! But come this way, Emmy; I mean to go out myself this fine morning, and take a look at the great human family, with my own eyes; maybe we can concoct something to set community in motion in our own way. [Exeunt]