Indians, Sources, Critics

Presented at the 5ᵗʰ Cooper Seminar, James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art at the State University of New York College at Oneonta, July, 1984.

Originally published in James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art, Papers from the 1984 Conference at State University of New York College — Oneonta and Cooperstown. George A. Test, editor. (pp. 25-33).

Copyright © 1985 by State University of New York College at Oneonta.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

PRIOR to European contact, the Algonguins lived in a broad east-west belt frcm the Rocky Mountains eastward to the Atlantic coast. Other tribes, mostly Iroquois speaking, were their neighbors in what is now the United States and Canada on both sides of the Great Lakes. On the Atlantic Coast from the Carolinas north to the St. Lawrence River, every tribe spoke an Algonquin dialect. Zeroing in on what are now the mid-Atlantic states, we find many diverse small bands of Indians living in their original milieu in Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, lower New York State and Connecticut. They called themselves Lenape which means simply ‘The People.’ In the early 1600s an Englishman, Lord De La Warre, scouted the area. His name was given to the bay and river where many Lenape lived. In time the Indians were called Delaware by map makers and historians. It is an English name, not a native one.

In the mid-Hudson region near present-day Albany on both sides of the river were Mohican Indians. Mohican is a convenient European contraction of the native word Mohicanyuk which can be translated as “people who live alongside a river which ebbs and flows.” Below the Albany area in the lower Hudson were a dozen other bands who were known as the Wappinger, an Indian word with a Dutch ending.

Indians living in the Connecticut area near the Thames and Mystic rivers were called the Mohegan Pequot. The Thames, Mystic and Connecticut rivers are all tidal rivers like the Hudson. It was a chief of the Connecticut Mohegan, Uncas whose name was used by James Fenimore Cooper to lend credibility and color to his protagonists in The Deerslayer and The Last of the Mohicans. The real Uncas was an ally of the English colonials in the Pequot War of 1636 and King Phillips War of 1676. In his fiction, Cooper places him in the French and Indian Wars in the 1740s. Fully aware of the anachronism, Cooper made the Delaware chief, Tamenund, a very old, partly senile ancient patriarch in 1745. Hearing the voice and accents of a young Uncas in The Last of the Mohicans, Tamenund learns that the Uncas standing before him is a grandson of the Uncas whom he had known as a youth. In this case Cooper uses poetic license and he uses it well.

Indian names on a Dutch map (circa 1650) show Algonquin forms:

| Prefix | Suffix | |

| Wappinger | Wapp | Inger |

| Wepowog | Wep | Wog |

| Wampanoag | Wamp | Oag |

The Algonquin prefix common to all three means light, white or pale. Wampom are white beads. Wapsini are pale faces. The suffix wog, oag can be spelled twenty different ways including uck, ack, aug. It means place. By combining the prefix and the suffix we get the “pale sky place” or the “dawn sky place” which expands to “the people of the dawn sky place” or “easterners.” Wappinger is an Indian word with a Dutch ending. Ich bin ein Berliner, Ich bin ein Amsterdammer, Ich bin ein Wappinger. There were sane twenty different Algonquin dialects among the tribes which were eventually called the Delaware and Mohican. The Europeans who recorded place names and Indian words for posterity came from England, France, Germany, Holland, Sweden, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Added to this acoustic cacophony was the lack of standardized spelling in English. Uniform spelling in written form did not cane until well after the first 150 years of Algonquin-European oommunication. All these factors contribute to the difficulty the historian, ethnologist or fiction writer has in using Indian names, words or idiom.

Three additional tribal groupings:

| Place | Word | Meaning | Dialect |

| New Jersey | Wapanucka | Easterners | Lenape |

| Connecticut | Wapanichki | Easterners | Mohegan-Pequot |

| Maine | Wabanaki | Easterners | Penobscot |

At the funeral of Uncas and Cora in The Last of the Mohicans, a noted Delaware warrior Uttawa, faces the dead body of Uncas and begins his lament: “Pride of the Wapanichki, why has thou left us?” Pride of the Wapanichki is the pride of the eastern people. Cooper in this instance obviously researched his material carefully and used the word correctly.

Cooper’s sources were many and varied. Before writing about Indians, Cooper was moved to read the diaries, journals, books and correspondence of the Moravian Church missionaries wine lived among the Delaware, Mohican and Iroquois from 1740 to 1820. He studied the works of Heckewelder, Loskiel and Zeisberger, which included Delaware and Mohican dictionaries. Several museums and learned societies in Philadelphia contributed to Cooper’s knowledge of the Lenape. Correspondence of members of the American Philosophical Society with individual missionaries were a treasure trove of Indian words. The name Chingachgook came from translations in a letter from Heckewelder to Deponceau of the Philosophical Society. Cooper did an excellent job of weaving descriptive matter from missionary writings into the fabric of his fiction. He adopted their favorable opinion of the Delaware as compared with the Iroquois and this shows clearly in his novels.

Also available to Cooper were the proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Colonial Records of Connecticut and the writings of Roger Williams. Captivity stories from New England, Ohio and Pennsylvania gave additional ideas for realistic and vivid drama to his novels. From New England historical sources we find the following family tree of chiefs of the Mohegan-Pequot, Narragansett and Niantic tribes.

TASHTASSUCK (Sachem of the Naragansetts)

(son)

Weesoum (Sachem of the Narragansetts) = Keshkecho

(son)

Canonicus (Sachem of the Narragansetts)

(son)

Mascus

Miantonomi

Sasious (Sachem of the Niantics)

Ninigret

(daughter) = Woipequand

Wopigwooit

Sassacus (Sachem of the Pequot)

Owoneco

Uncas (Sachem of the Mohegans)

(daughter)

In his fiction Cooper used the names of several of these chiefs and their associates. They appear not only in the Leatherstocking Tales but also in The Sea Lions, The Redskins, and The Wept of the Wish-Ton-Wish.

The Federal government in Washington had a policy of inviting selected leaders of frontier Indian tribes for visits with the Great White Father. These pilgrimages were well covered by the press. The federally funded trips had several purposes. The Indians usually reviewed marching troops, saw and heard cannon fire and noted the large crowds in the cities they visited. They took back the message that to fight white encroachments would be futile.

In 1821 a Pawnee visitor, Petalasharo, came with seventeen other plains chiefs. Petalasharo became the toast of Washington. He was known to have saved a Comanche girl captive from ritual torture and then helped her to escape. Cooper met the chief and liked him. Five years after Petalasharo’s visit, Cooper wrote The Prairie. In this tale, the Pawnee are the good Indians and their traditional enemy, the Sioux, are the bad guys. The fictional Pawnee hero Hard Heart saves captives from torture and helps the frontiersnan evade the Sioux.

Cooper also made a point of visiting with and studying Indian delegations, usually in New York City or Albany. In 1842 one such group of chiefs detoured to Norwich, Connecticut, to attend the dedication of a monument to the Connecticut Mohegan chief Uncas. This historical figure had fought on the colonists’ side in Indian wars of 1636 and 1676. During the ceremonies a western chief surprised the audience by mentioning an incident in an ancient battle wherein a young brave outran a high enemy chief, jostled him, slowed him up but denied himself the honor of making the capture. Instead he maneuvered the enemy warrior into the path of his own chief. Indian custom held that it was fitting that a chief should capture a chief. The astonished audience recognized the origin of his oral recitation in a celebrated incident in a Mohegan-Narragansett war almost two hundred years earlier. Four years after the dedication of the Uncas monument, Cooper wrote the last book of the Littlepage trilogy. In The Redskins seventeen western chiefs returning from a visit to Washington go back by way of upper New York State in order to visit and honor a very old Indian. As a young chief this Indian had conformed to Indian laws regarding women captives by denying himself personal happiness. His action had saved his band from factionalism and earned him the title of the Upright Onondaga. The white audience was amazed to hear western Indians ask informed questions about a border skirmish which had taken place locally about eighty years earlier. Here again Cooper transposed places, events, and people because of the demands of his plot. Although he placed them in a new setting, he preserved the essence of Indian traits, actions and behavior in his scenes.

The food economy of the coastal Algonquin was heavily dependent upon shell fishing along the shore and farming in cleared fields close to their principal villages. Fresh water fishing in lakes, along rivers and streams with special fishing areas for each band was also important. The streams were useful also for transportation to forest sources of berries, nuts, fruit and maple sap. Canoes carried the more vigorous, younger and more mobile families to wintering places upstream where hunting and trapping could supplement fishing through the ice at favored ponds and lakes.

Originally there were six villages near the shore in present-day Milford, Stratford, Bridgeport, Fairfield, and Westport. In only twenty-five years the settlers fenced in their families and fenced out most of the Indians. Eighty acres in downtown Bridgeport were established as a reservation for the remaining Paugussets and Wepawogs. This was reduced to forty acres and then twenty. (In 1984 this reservation has shrunk to a quarter of an acre in Trumbull, Connecticut, with one house and one Indian family.) Some of the Indians moved up river establishing new villages at their old seasonal campsites. A farming, fishing economy continued but had to be supplemented with basketry, coopering, carpentry, whaling and by trading with and working for Europeans. Tne lower Housatonic Indians spoke a Munsi dialect. By 1700 stragglers from all the other Connecticut bands joined the new villages, bringing with them the accents of four other Connecticut dialects. The largest number of newcomers to upper Housatonic villages were Mohicans from the mid-Hudson and Wappingers from the lower Hudson. By 1740 Mohican had become the dominant dialect at Scaticook (Kent), Wequadnach (Sharon), and at Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Another large village at Pootatuck near New Milford and Newtown, Connecticut, received an influx of Mohicans in 1735 when a Mohican band from New Preston, Connecticut, broke up after the death of a chief.

In 1740 Moravian preachers established their first mission to the Mohicans of Shekomeko just over the border in New York colony. A map by Loskiel shows three other satellite missions which were established at Pootatuck, at Scaticook and at Wequadnoch, all in the upper Housatonic hinterland in northwest Connecticut.

Cothren’s History of Ancient Woodbury [Conn.] tells little about individual Indians who lived in the region in the decades of the 1730s and 1740s. We know that Atchetousset had a daughter who was converted by the Moravians. Another Indian, Job, went with the preachers to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, according to a page written in eighteenth-century German script from one of the Scaticook Mission diaries. It tells of a trip by one of the brothers and several Indians to the northern headquarters of the Moravian Church in Bethlehem. Job’s Indian name was Wasamapah which means “he crosses over back and forth.” Since Job lived at Scaticook, Connecticut, and Shekomeko, New York, the name may be descriptive of his trips back and forth to and from these villages.

The first two converts were Shabash and Tschoop. The Moravians wrote extensively about these two Mohicans and their helpful influence in converting other Mohican and Delaware. Shabash means “running water.” I was unable to translate Tschoop. One diary describes Tschoop as a man with broad shoulders, a barrel chest and huge arms, a physique “more like a bear than a man.” In time I learned that the missionary who first met Tschoop pronounced the letter B as though it were a P. In his German dialect Job sounded like Tschoop. Other recording preachers thought Tschoop was an Indian name and referred to him as Tschoop in their diaries. At Bethlehem I was surprised to learn that the grave of Tschoop (Job) baptized as Johannes or John was visited in the century following 1820 by more than a million people. Job was one of three Moravian Indians whose lives were studied by James Fenimore Cooper. From what he read of them, Cooper fashioned the character of Uncas and Chingachgook in the Leatherstocking series. Posthumous fame and an initial stream of visitors came to Tschoop seventy-five years after his death when The Pioneers was published. Even today people come to see the grave of “The Last of the Mohicans.” The headstone of Tschoop’s grave is in Gottes Aker at Bethlehem where he died in August 1746.

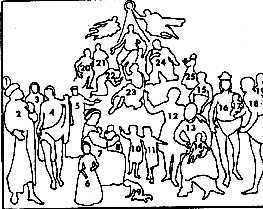

A painting of the early converts from their mission stations around the world was created by John Valentine Haidt. Tschoop is shown kneeling at the left hand of Jesus. He is number 24 on the list of figures in the work. Thomas, a Huron, is number 20. Haidt’s oil portrait was called the First Fruits. A close-up of Wasamapah shows him physically very much like his written description. A Housatonic Valley Mohican named Joshua was another Moravian Indian whose biography and personality contributed to the development of the character of Uncas/Chingachgook/John/Mohegan/Indian John in Cooper’s novels.

The Delaware and Mohicans described by the Moravians lived in the period 1740 to 1820. The missionaries did not fully appreciate the mixed-up, composite nature of the tribes with whom they dealt. By 1740 when the Moravians appeared on the scene the Connecticut Indian population was about twelve percent of its size a century earlier. The missionaries accurately described Indian life as they saw it in the middle and late eighteenth century. They did not completely understand the relationship between the Delaware and the Mohican in the jumbled-up remnant groups to whom they ministered. Some of their misconceptions show up in Cooper’s work. The Mohicans Uncas and Chingachgook in The Last of the Mohicans are accepted as chiefs by a Delaware band on the basis of turtle clan tattoo on their chests. The incident made an excellent spellbinding scene. Cooper’s dramatic enthusiasm was so successful that we should perhaps overlook whatever ethnological inaccuracies are involved.

Moravian reports were the single most important source of data, background anecdotes and plots for our author. New England historical publications gave him Indian names, and a few battle scenes which lent authenticity and credibility. From his acquaintance with Petalasharo and other delegates to Washington came material for The Prairie and The Redskins. One additional source, his correspondence with the celebrated Chippewa historian George Copway, gave him ammunition to reinforce his use of and belief in the accuracy of Indian oral history and picture writing. Copway’s support was helpful also in firing back at the sniping at his Indians by General Lewis Cass which continued throughout Cooper’s lifetime.

A militia officer, politician and federal Indian agent became one of the most persistent critics of Cooper’s Indians. Lewis Cass was appointed governor of Michigan Territory in 1813 when there were sane four thousand whites and forty thousand Indians in the region. Cass’s duties for the next eighteen years included making room for more settlers. To do so he negotiated treaties with many tribes sometimes abrogating or revising them unilaterally. His frequent meetings with Indians were often confrontational and unfriendly.

In 1823 he printed a list of four hundred questions about native life and habits. The questionnaire was circulated among frontiersmen, settlers, trappers, soldiers and traders who dealt directly with the red men. Interpreting the data collected from these agents in a manner which reinforced his negative opinions of native Americans he wrote a pamphlet on Indian life, manners and customs. Cass sent a copy to Cooper and a letter which pointed out his many objections to Cooper’s portrayal of the Indians. When the next Leatherstocking tales continued to reflect Moravian observations rather than Cass’s, Cass angrily accused Cooper of writing about Indians “in the school of Heckewelder rather than in the school of Nature!” Eventually Cooper replied in the preface to a later edition “Who knew the Red Men best? The missionary or the Indian Agent?”

Today it is clear that Cass perceived the popularity of the noble savage concept as a threat to his political ambitions, official duties and perhaps to his self-image. In 1848 Cass ran for the presidency of the United States. His reputation as a frontier expert and Indian fighter was a strong plank in his platform. By voting Zachary Taylor into the White House, the public may be said to have rejected Cass’s callous unfeeling interpretation of Indian character. It is an interesting speculation as to what extent the popularity of the Leatherstocking Tales helped to mold voter opinion in the election. Three decades of complaining about Cooper’s Indians helped to keep Cass’s name in the public eye. Cass’s long crusade was self-serving. In the long run it did him little good and Cooper little harm.

Years after Cooper’s death Mark Twain discovered literary criticism to be a profitable enterprise. Cooper’s novels became a favorite target of his sharp wit. He pointed out repetitive instances in the Indian stories where frontiersnen or Indian trackers followed their quarry through the forest by noticing broken twigs. Twain wryly suggested that the Leatherstocking series should be renamed, “The Broken Twig Series.” With considerable cause, Twain complains of the wordiness and excess verbiage in Cooper’s style. From one 350-word example Twain deleted one hundred words without any loss of meaning. Indeed, his editing improved the clarity of the passage. As an accomplished writer, humorist and critic he had adequate stature to expound on what he called “Cooper’s Literary Offenses.” When lampooning Cooper’s style, Twain was at his satirical best. His criticisms of Cooper’s literary style may have merit.

But Twain also criticized Cooper’s portrayal of Indians. He wrote that he himself had gone West eager to meet Indians like Cooper’s heroes only to encounter miserable, degraded, drunken specimens of a tribe he derisively called “The Goshoots.” His dislike of the Goshoots and 611 Indians is clear. At one point Twain says, “a Cooper Indian who has been washed is a poor thing. It is a Cooper Indian in his war paint that thrills.” Some researchers have suggested that his anti-Indian bias reflected the views of his wife’s family. Whatever the reason, his dislike of the red men shows in his essay “Fenimore Cooper’s White Novels.” Here he ridicules the white minority who intellectualize the red man. Twain assures us that “malice is the basic feeling of the Indians toward the white.” He speaks in racist generalities about Indian men and white women and about Indian girls and white men. While admitting that Cooper has done more than anyone to present the red man to the white man, he objects that the presentation is a form of unrealistic wish fulfillment. Finally Twain states that modern critics begrudge Cooper his success and admits that he resents it a little himself. He trivialized matters and cheapens what little value his views on Indians have by referring to Chingachgook sarcastically as “Chicago.”

When commenting about Cooper’s literary clumsiness Clemens was unkind but not unfair. When writing about Cooper’s Indians, Mark Twain exhibits some of the racial attitudes of a nineteenth century Archie Bunker. His comments about real Indians and Cooper’s Indians cannot be taken seriously.

In Following the Equator he made devasting comments about Jane Austen, Alexander Pope and James Fenimore Cooper. In lancing at literary figures with his sharp pen, Twain enjoyed himself, made good money, and overdid it. He wrote for humor not for accuracy. Twain’s tone in much of his lampooning was tongue-in- cheek. In recent years his criticism has been taken more seriously than he intended. Many literature teachers use Twain today as an excuse to avoid the formidable task of familiarizing themselves with Cooper’s novels, essays and correspondence. “Don’t read Cooper, just read what Twain says about him” is a phrase which has deprived many of the current generation of the chance to know one of the most prolific writers of the American scene.

The historical records of southern New England gave Cooper knowledge of names, traits and behavior of Indians who lived in the period of early white contact 1620 to 1680.

His Moravian source materials were written by missionaries to the Algonquin and Iroquois from 1740 to 1820. They dealt with natives who lived during historical events which were the setting of some of Cooper’s tales.

Cooper’s meetings with Petalasharo and other western chiefs from 1820 to 1848 gave him insight into the problems, attitudes and habits of early nineteenth century plains tribesmen. General Cass and Mark Twain compared Cooper’s fictional eighteenth century Indians with the Indians they themselves met in the nineteenth century. While accusing Cooper of romanticizing and idealizing the red man, both critics conveniently ignore the fact that Cooper’s nineteenth century Sioux in The Prairie are thieving rascals.

In his doctorial dissertation “The Influence of the Moravians on The Leatherstocking Tales,” Edwin L. Stockton correctly concludes that Cooper was a romanticist in inventing his plots and a realist in portraying his Indians.

Notes

1. “Indians, Sources, Critics” is based on a lecture with slides presented at the 1984 Cooper Seminar.