The Leatherstocking Tales as Adapted for German Juvenile Readers

Presented at the 5ᵗʰ Cooper Seminar, James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art at the State University of New York College at Oneonta, July, 1984.

Originally published in James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art, Papers from the 1984 Conference at State University of New York College — Oneonta and Cooperstown. George A. Test, editor. (pp. 41-45).

Copyright © 1985 by State University of New York College at Oneonta.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

From 1845 to 1980 more than seventy different adaptations for juvenile readers of the Leatherstocking Tales have been published in Germany, an impressive variety that brings up the question: What — and why so — has been changed here?

Going back to the first edition for young Germans, we see that Franz Hoffmann not only started the whole matter, but also gave it its rules, reducing the texts in length by two-thirds, arranging them chronologically, abandoning what seemed dubious or complicated to him, whether it be political or moral aspects of just items of no immediate necessity for the plot and sometimes also adding what appeared more appropriate. He thus stressed the adventure story at the expense of the story proper, which points to why, apart from promising safe business after having passed both the censor and a wide reading public, the Leatherstocking Tales have become favorite objects of adaptation. They are clearly organized on two levels: that of the adventure tale, supplying most of the outward plot for about the first three-quarters, and that of the underlying novel of manners, being prepared in the descriptive and reflective parts and in the digressions of taking over the plot towards the end; a structure literally inviting the Germans again to cut off what refers to concepts unknown to them and to concentrate on the familiar elements instead, which were also likely to be preferred by children. Adaptation is thus going on in two steps: that of the adapter’s reception of the original text, a mainly subconscious process occurring at any reading, when we select (by skipping lines or even pages) and substitute (by reading into the story) and thus deform a text to our own version of it, usually a transient one, but getting materialized in print with the adapters, thus anticipating and manipulating the reactions of the new readers; and, secondly, the production of the new text, including distinct intentional elements described best by rhetorical categories, above all that of aptum, meaning that a text is ‘apt’ both to its audience and to the persuasive aims of its author, which implies that it will have to be ‘ad-apted’ in case of a change of either.

Following Hoffmann’s example, all later versions also move along these patterns: they don’t end the series with the pessimistic Deerslayer and Cooper’s cutting the line to the United States of his day, but with the Prairie, harmonizing ethnical and social contrasts and offering an optimistic outlook on America’s future. Cooper’s discussion of general American themes is thus reduced to an individualistic ‘Life of Natty Bumppo’ with consequently The Pioneers being called ‘Leatherstocking’ or ‘The Old Hunter,’ and The Prairie emerging as ‘The Old Trapper’ or ‘The Prairie-Hunter’ or ‘Leatherstocking’s Last Adventures’ or simply ‘The End of the Leatherstocking.’

In the course of the Tales the main plot usually remains undisturbed throughout the first three quarters, while minor plots and characters (e.g., Christmas in Templeton, or David Gamut) and other elements of thematic importance like Cooper’s highly symbolic descriptions of nature, his ethnographical, historical and geographical surveys and his religious, philosophical and political discussions are mostly regarded as merely ornamental and thus shortened or even disposed of at random, just as the epigraphs disappear to be replaced by promising headings like ‘Cruel Combat,’ ‘Fight for Life and Death,’ or ‘Revenge.’ All that again ends up reducing the texts to adventure plots and avoiding anything that would not fit in or mean their suspension or delay, which makes clear why The Last of the Mohicans, allowing such adaptation to the greatest extent, has become the most popular tale, closely followed by Deerslayer and The Pathfinder, whereas the other two hardly ever occur on their own. It also shows that the adapters knew exactly what they were doing, as is reflected by the great popularity of the very short versions too.

While sub-plots and minor characters as well as descriptive and reflective elements could easily be removed without much consequence for the adventure plots, though of course not for the meaning of the stories, it was nearly impossible to abandon the great central conflicts or the plots would have collapsed towards the end, so they had to be reinterpreted and re-set, as they could not be kept in the original versions either, because, on the one hand, they would have become largely redundant and incomprehensible having been stripped of their background and their leading abstract concepts, and, on the other, they often present topics and attitudes that were not thought fit for German youngsters.

Self-censorship for these reasons is mainly enacted in three fields: first, sex and crime, however harmless with Cooper, but still not harmless enough for young Germans, second, any kind of ambivalence or uncertainty as in open endings, irritating the pedagogues with their addiction to clear-cut black and white all-round solutions; and third, even the slightest traces of resignation or pessimism, as in sad endings, disturbing the pedagogical concepts of the so-called “positive.” This background points to why The Deerslayer has become the adapters’ most prominent victim and explains the kind of changes they have performed on it.

To begin with, Mrs. Hutter is made an honest woman by the father of her children, sometimes still a British officer, but more often a travelling merchant or even a ship’s doctor or a captain. The latter come in handy for establishing contact with the pirate Hutter and for allowing the first husband to take a decent leave by dying of malaria or sinking with his ship or being killed by Hutter’s gang the buccaneer himself, who subsequently robs mother and daughters and drags them off to the wilderness, upon which the innocent lady surprisingly consents to marry the villain, although she is usually well equipped with a set of helpful relatives both in Boston and in England who receive Judith and Hetty most cordially at the end. Hetty therefore survives, for to kill her off would not do in a genre always rewarding virtue. Instead Harry is sometimes hit by the bullet himself, as the proper answer to his ruthless attempts at scalping. In versions sparing him, his morals have to be improved, just like those of old Hutter in those editions which save themselves all the trouble with his wife by leaving him father of the girls, who, this way or other, are hardly ever exposed to any indecent temptations, one of the adapters’ main concerns. Especially, the unpleasant Warley affair is always neutralized, with him being either just a polite officer seeing the girls safely off to their relatives, or, if none available, assuring them of his and his wife’s(!) assistance. Sometimes he even turns out to be a remote uncle or a grateful ex-patient of their late father! On no account, however, would any improper conduct in an officer or any love affairs other than those directly aimed at marriage be tolerated, which also explains why Chingachgook and his bride can be left as they are, whereas Judith’s fate has to be corrected by providing a decent match, also saving her the trouble of proposing to Natty and of his rejecting her. Instead she is married off either to Warley or even Harry, who don’t declare themselves until the very end though, or more often to either a worthy shipbuilder or an honest merchant or a brave officer or even a famous general, to name just the most outstanding characters in her long line of husbands, a point stimulating the adapters’ inventiveness like few others.

This way Judith can kill two birds with one stone: achieving an honest name and thus a respectable identity as well as being provided with a safe and comfortable living, which make her inevitably end up in perfect happiness and harmony, settled in a pleasant home among nice children and a loving husband and assisted by Hetty as her housekeeper, whom, strangely enough, nobody ever tries to get married, obviously still accepting Cooper’s rather dim explanation of her feeble-mindedness, though meanwhile a redundant feature, as a given fact.

Similar devices are applied to the other four novels. In The Last of the Mohicans, for instance, all aspects asking for trouble — and getting it later on — are abandoned right away: Cora’s fatal lineage and the subtly drawn tensions between the doomed beauty and the two young Indians as well as the crucial interview of Heyward with his future father-in-law. Uncas’ death being indispensable, at least the Munro family can be spared the tragic outcame of the enterprise: often Cora remains alive, though she, too, becomes her sister’s unmarried companion, which again indicates the persistence of Cooper’s restraint despite the elimination of its causes in the new versions. Sometimes her tragic end is also kept for the sake of the picturesque scene, whereas old Munro is usually still given several peaceful years of retirement. Anyway, he and the Heywards keep sending presents to the Delawares at each anniversary of their victory over the Mingos. But The Last of the Mohicans is also notable for another type of alteration, that is, the highly suggestive and significant scenes of acute and intense cruelty and violence, like the killing of Gamut’s young horse or the scalping of the friendly French soldier, that involve the reader very closely by surpassing the usual stock patterns, which the adapters of course do not hesitate to reduce quickly, provided they keep them at all, although otherwise they usually never miss a chance to indulge in combat scenes.

The changes in the other novels vary little from these models, though not quite as spectacular as just described. In The Pathfinder Muir’s foul play is either understated or even left out (which saves him from being stabbed) or Natty’s hint of such a villain being only possible with Mingo blood in his veins is overemphasized in which case Muir is denied even the modest burial he gets from Cooper. June, having lost her function as a counterpart to Natty now, occasionally stays alive and with Mabel, joining Cooper’s gallery of single housekeepers, while the Sergeant’s daughter and Natty are spared the awkward experience of rejected courtship, which allows the latter to remain the untempted, unscathed he-man throughout the book, never being depicted in moments of weakness, uncertainty, frustration or suffering and thus gladly handing Mabel over to Jasper. Quite frequently even that rudiment is omitted, though, as the Sergeant often stays alive, his death no longer required as a means of getting Natty into trouble. Consequently none of the painful feelings of loss befall Mabel either, so that there is once more nothing to stop the story from moving towards a perfect happy ending.

In the last two novels all unpleasant characters are reduced either to plain fools and their actions to harmless, involuntary minor offenses, to individual incidents of no greater or general significance, or all evil deeds and tendencies are personified in the central villains, functioning as scapegoats for the other characters. The archaic Bush clan, for instance, become slightly rude but well- meaning country folk with Abiram as their black sheep, who, however, need not encounter his ghastly execution, but is usually given a rifle or even a pistol, enabling him to draw the consequences like a gentleman.

Apart from such striking changes in plot and meaning, the fact that texts are reduced to as little as five percent of their original length and adapted to the reading habits of so different an audience also requires substantial modifications in narrative technique. The most characteristic and widespread are the omission or at least delay (and reduction) of Cooper’s exposition for the sake of starting right in the middle of the action scenes, the flattening of characters by confining their presentation to stock devices, and, on the whole, a strong tendency to simplify and level out and shift emphasis and perspective from the auctorial point of view to scenic presentation which, along with its thematic implications, also accounts for the predominance of action scenes over narrative, descriptive and reflective elements, due both to the latter being less attractive to children and to general literary trends as well as to the basic transformation of Cooper’s novels into mere adventure tales.

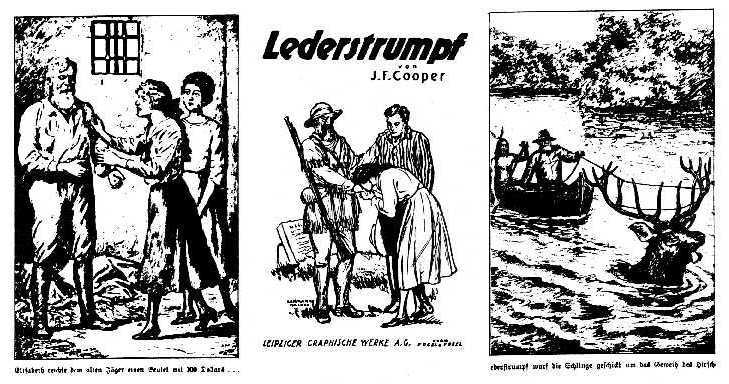

Finally, far-reaching stylistic adjustments of literary devices and syntactical structures and vocabulary both to the historical changes in taste and to the abilities and likings of the new readers have helped to make the Leatherstocking Tales up-to-date juvenilia. Again, mainly by simplification and reduction on the one hand and assimilation to familiar patterns and elements on the other, deactivating and domesticating literary texts, further emphasized by illustrations following the same principles, in which words and pictures underline the general tendency of the German adaptations, suffocates the emancipatory force of literature by impeding a free and independent access and taking the reader “by the hand” instead.

The following enviably self-confident comments of adapters on their products, published between 1909 and 1949, illustrates what is being done to texts here:

The original text is like a thick overgrowing hedge, with plenty of little branches every here and there, at which knife and scissors cutting off and clearing out will do no harm, but ... improve the general impression ... and make the plot move along more swiftly and rapidly. ... In order to make access easier, I have transferred all events into present tense and have given titles to the chapters. ... Apart from that, however, I have refrained from any material interference, which the author would not have deserved. ... My main concern has just been to work out more clearly what Cooper had actually had in his mind.

Notes

1. Black and white illustration from the collection of Irmgard Egger, many of which were displayed at the 1984 Seminar and some reproduced with her paper; colored illustration is from a German juvenile “Leatherstocking Tales” in the possession of Hugh C. McDougall of the James Fenimore Cooper Society.