Cooper’s Revisions for His First Major Novel, The Spy (1821-31)

Presented at the 12ᵗʰ Cooper Seminar, James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art at the State University of New York College at Oneonta, July, 1999.

Originally published in James Fenimore Cooper: His Country and His Art, Papers from the 1999 Cooper Seminar (No. 12), The State University of New York College at Oneonta. Oneonta, New York. Hugh C. MacDougall, editor. (pp. 88-107).

Copyright © 2000, James Fenimore Cooper Society and the College at Oneonta.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

{88} Electronic technology may eventually put out of business anyone concerned with editing a text prepared by an author for public presentation. Today, authors have the capacity to create text (in many cases enriched text using visualizations or music) by working at computer terminals. Authors can even exercise the option to dictate text using increasingly friendly software packages that will turn their dictation into words. Such authorially-prepared text can easily be revised at the terminal, and prepared for print publication through camera-ready reproduction of texts under the author’s control the entire way from genesis to mass market. And electronic publication over the Web eliminates paper reproduction altogether.

Such technologies were obviously not available to James Fenimore Cooper in the early 19ᵗʰ century. Indeed, the technology of publication used for his novels published between 1820 and 1850 was essentially the same technology available to Johannes Gutenberg 400 years earlier. That is, Cooper delivered the manuscript of his works in his own hand to a typesetter who laboriously set the type character by character, line by line, page by page, eventually producing proofs that the author (depending on his travels and other writing projects) might spend greater or lesser time in revising. Cooper might also, at various stages of his career, make use of family members who served as amanuenses, copying down the author’s text from dictation. Again, depending on his other commitments, Cooper might or might not review such amanuenses’ copy with care.

Following the initial inscription of Cooper’s own words (written or verbalized) presented in the first edition text, Cooper did in fact often take the occasion to revise his earliest novels. In the first decade of his career as an author between 1820 and 1830, Cooper wrote 10 novels, including some of his best known — The Spy, The Pioneers, and The Last of the Mohicans. During this decade he also grew significantly as an artist, learning his trade well in terms of moving his plots ahead briskly and trimming the sometimes-laborious prose of his earliest works. His efforts during this decade in revising The Spy (1821) were especially important to his development as a professional author. Cooper had complained bitterly about poor type-setting to the publisher of his first novel, Precaution (1820): “I wish my own language printed — having quite as much faith in my own taste as in that of any printer in the union — let them give me a fair chance — the work is mine and I am willing to keep the faults — let my book be literally my own. They cannot possibly understand my meaning as well as myself.” 1 But Precaution enjoyed little public success or notice: and no reprintings were called for after its initial appearance until 1839, when Cooper revised it for republication in Philadelphia and London.

The Spy proved, to Cooper’s delight, to be a different matter altogether. Cooper informed Goodrich, his first publisher, on June 28, 1820, that “I have commenced another tale to be called the ‘Spy[,]’ scene in West-Chester County, and time of the revolutionary war. ... The task of making American Manners and American scenes interesting to an American reader is an arduous one-I am unable to say whether I shall succeed or not. ... ” 2 By grafting the conventional love intrigues of Precaution onto an exciting “spy novel” plot enriched with political analysis as well as vivid scenes of military action, Cooper succeeded in creating his first masterpiece and his first bestseller. This graft is effected economically: the two young Wharton heiresses, Sarah and Frances, fall in love respectively with a British and an American officer, intertwining the love interest with a depiction of the American revolution as a civil war between competing financial interests as much as a war of independence.

Published shortly before Christmas 1821, Spy quickly sold out, necessitating new hand-set printings in March and again in May 1822. Cooper repaired the worst of his and his printers’ blunders in these second and third editions, and then turned his attention fully to his next novel, The Pioneers of 1823. In 1831, Cooper seized the opportunity presented by an advantageous business relationship with Richard Bentley, one of London’s leading publishers, to revise the texts of no fewer than six of his early novels, including Spy. The Bentley contract called for introductions and explanatory notes which provided Cooper with an opportunity to contextualize his early novels in what he saw as his increasing contribution to defining in fiction the history of the young Federal Republic. In addition, the opportunity to revise for the prestigious Bentley Standard Novels series offered Cooper an opportunity to remedy the defects of many of his earlier works.

Cooper’s revisions offer significant challenges to the editor to determine which of the changes that appear in these three reprintings are Cooper’s own work, and which are the intentional or unintentional changes imposed by house styling and compositors. Some changes to the first edition text are fairly easy to deal with. The London publishers, for {89} example, regularly changed all of Cooper’s American spellings to equivalent British forms, and frequently were baffled and thus regularized Cooper’s many dialect spellings and registrations of dialect pronunciation. But what does an editor do with the hundreds of other variants — from changes in punctuation to changes covering several pages — that appear in these three revised texts?

Fortunately, editorial theory and practice have developed for centuries, impelled initially by the need to produce reliable texts for religious works such as the Bible. Beginning in the 1950’s, textual editors began to use as their fundamental or “copy text” the version closest as possible to the author’s original inscription — the manuscript if it were available, or the first printed edition. The argument was that the text closest to the author’s first inscription would capture his practices for spelling and punctuation (“accidentals” in the jargon), as well as for the substantive meaning of the text. While later reprints of the printed text closest to the copy text might correct mistakes that the author or his proofreaders missed in the first edition, such reprintings would inevitably introduce corruptions of the author’s meaning.

Following such editorial practices, the editors of the “Writings of James Fenimore Cooper” have created “eclectic” texts-that is, texts which the editors believe represent that final intention of the author for his work. Eclectic scholarly texts include all changes subsequent to the earliest form of the text (the copy text) which the editors believe come from the author’s hand, and correspondingly, reject all changes in later editions which the editors believe do not originate with the author. The “Cooper Edition” text of The Spy, for example, was created by inserting into the first edition (the manuscript is missing) all the variants the editors believe originate with Cooper, and rejecting all those not judged as authorial.

To be more specific, conventional editorial practice generally rejects changes in punctuation or spelling that occur in editions after the first, reasoning that such changes originate more likely from the typesetter’s preferences or oversights than from authorial intervention. Conversely, variants effecting changes in meaning resulting from new wording are more likely to originate with the author; typesetters are unlikely to take the trouble to make such changes because replicating the exact typesetting of the edition they are working from, line by line, is the easiest way to get their jobs done. For The Spy, the task of determining Cooper’s intention, at least with respect to the Bentley Standard Novels edition, is unusually straightforward because, for The Spy, editors have available the virtually complete physical document containing the revisions Cooper made for the London publisher in 1831. From examination of this manuscript (in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library), we can simply see the specific changes Cooper made, from adding or deleting a comma to changing a single word to altering whole paragraphs. (“Simply see,” that is, once the editor gets used to Cooper’s script!) The examples below, keyed to illustrations of the text Cooper worked on, disclose the range of changes Cooper made and the Cooper Edition thus follows in our edition of the novel, scheduled for publication by AMS Press in 2001.

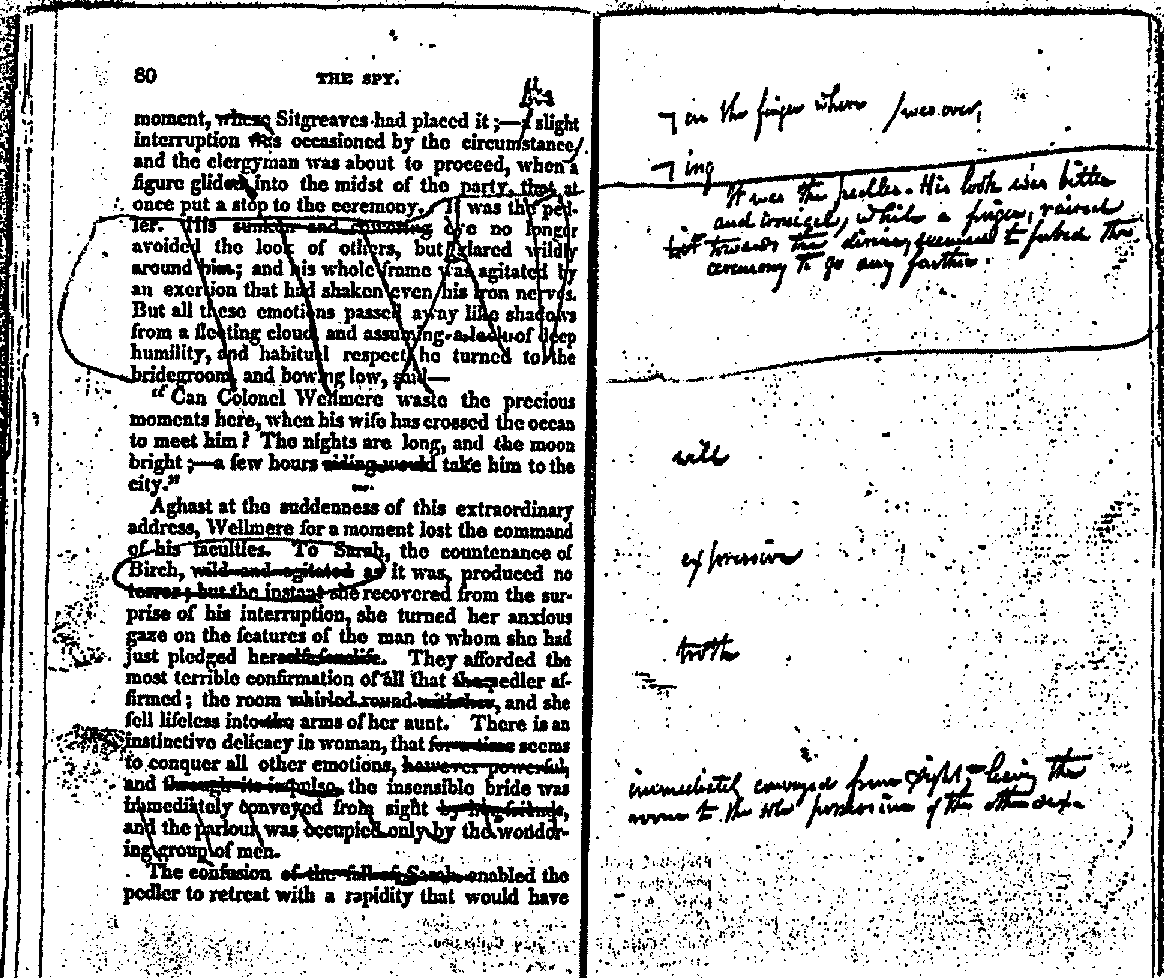

Physically, this text was prepared by Cooper having his publishers interpaginate blank sheets of writing paper with a Philadelphia edition of The Spy, permitting the author to write his changes more or less in parallel with the text he is altering. Illustration 1 is the very first page of Cooper’s revision. Of special interest to the editor is Cooper’s deletion here of seven commas (his deletion sign looks like a crooked “7” in the right margin). Without the physical evidence that these changes were Cooper’s, an editor would normally reject them. But Cooper here, as on many other pages, is deleting superfluous punctuation, speeding up the pace of reading for an audience who would (as often in the nineteenth-century) encounter the novel read aloud in the family circle. On the first page Cooper also added one of the 16 footnotes prepared to assist British readers in understanding historical and geographical contexts for the book. Cooper’s explanation that American states are generally divided into counties, and that West Chester was the county closest to New York City, provides useful information for the contemporary American reader as well.

Finally of interest on this page in the comment faintly written on the top left side: “G.P.R. James always began his novels with two horsemen seen approaching.” The source of this facetious comment is unknown, but the observation shows Cooper was using a formulaic opening well appreciated by contemporary readers — a sign of his quickly developing as a professional.

Illustrations 2 and 3 further show Cooper’s care to supply footnotes that provide political contexts for readers who might not recognize allusions to the heritage shared by those who had lived through the Revolution two generations earlier. The notes on Illustration 2 celebrate the patriotism of American yeomen like John Paulding (1758-1818) who resisted bribes offered by John André and turned the British spy in to American authorities in September 1780. Paulding’s selfless loyalty parallels the fictional patriotism of Harvey Birch, the chief spy of The Spy. In Illustration 3, Cooper contrasts American and European practices by asserting that “In America, Justice is administered in the name of ‘The good people &c &c.’ the sovereignty residing with them.”

{90} Illustration 4 is more complex, and typifies dozens of sites in the revised 1831 Spy where Cooper simplified an overwrought description. In this melodramatic scene, Harvey Birch mysteriously emerges from nowhere (as is his wont) to warn an American of impending danger, in this case, to stop the infatuated Sarah Wharton from marrying an already-wedded British officer. The over-written depiction of a hectic Birch was replaced with simple but admonitory language: “It was the pedler. His look was bitter and ironical, while a finger, raised towards the divine, seemed to forbid the ceremony to go any farther.” Other changes on the page continue this tactic; in the next paragraph a reference to “Birch, wild and agitated” is changed to “Birch, expressive. ... ” Additional authorial variants continue the pruning of such agitated language to reduce the melodrama of the original text. At the bottom, the passage “There is an instinctive delicacy in woman, that for a time seems to conquer all other emotions, however powerful, and through its impulse, the insensible bride was immediately conveyed from sight by her friends, and the parlour was occupied only by the wondering group of men” becomes more simply, “There is an instinctive delicacy in woman, that seems to conquer all other emotions, and the insensible bride was immediately conveyed from sight, leaving the room to the sole possession of the other sex.”

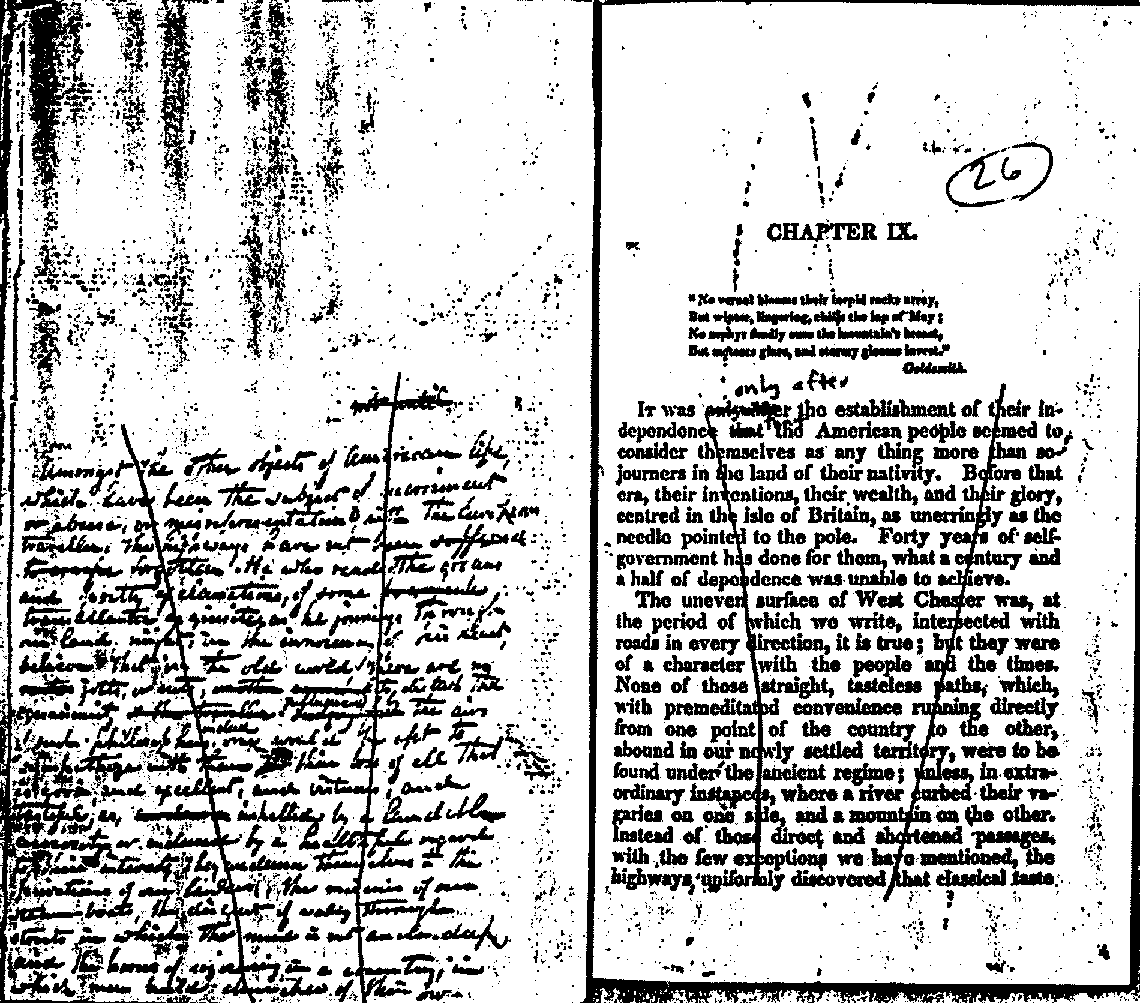

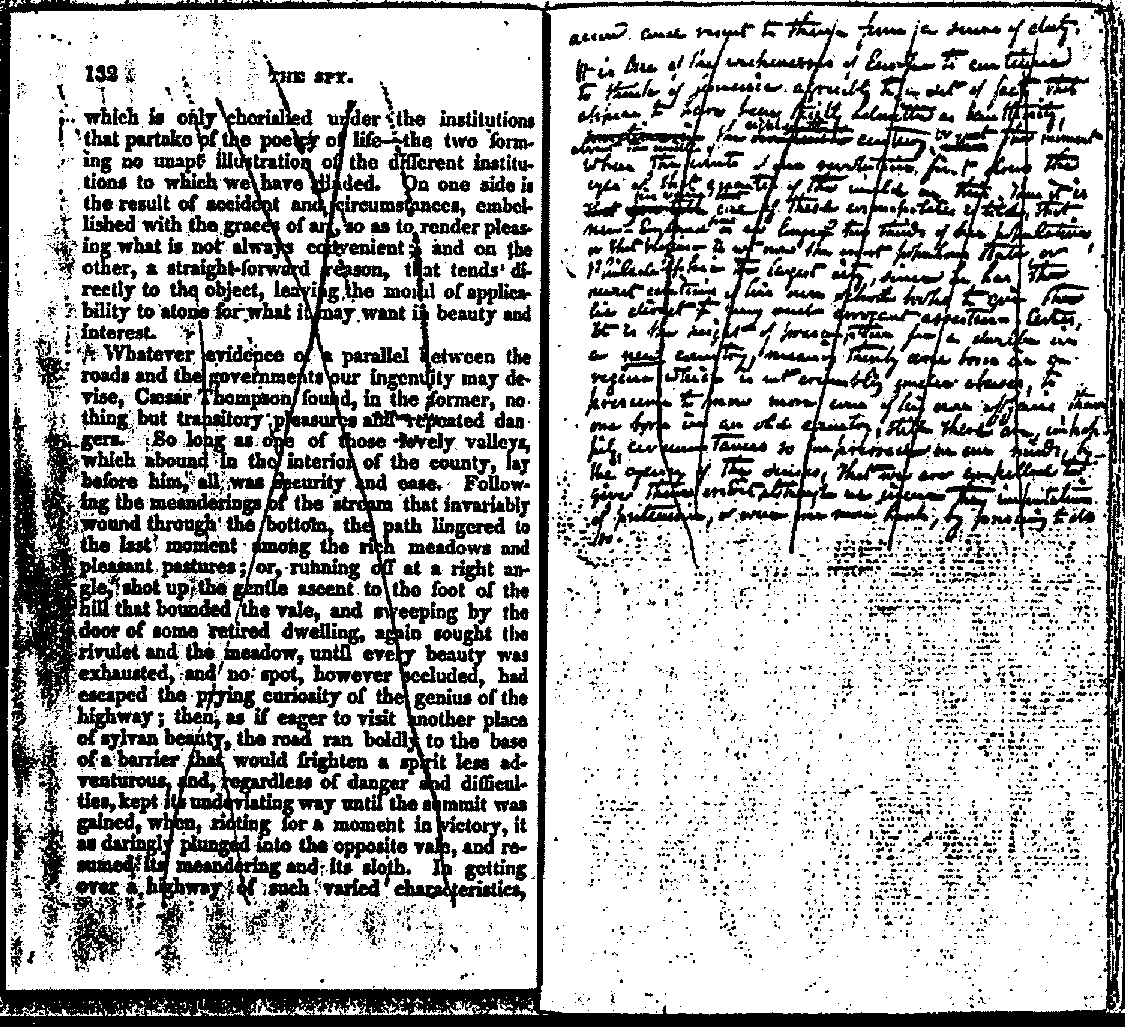

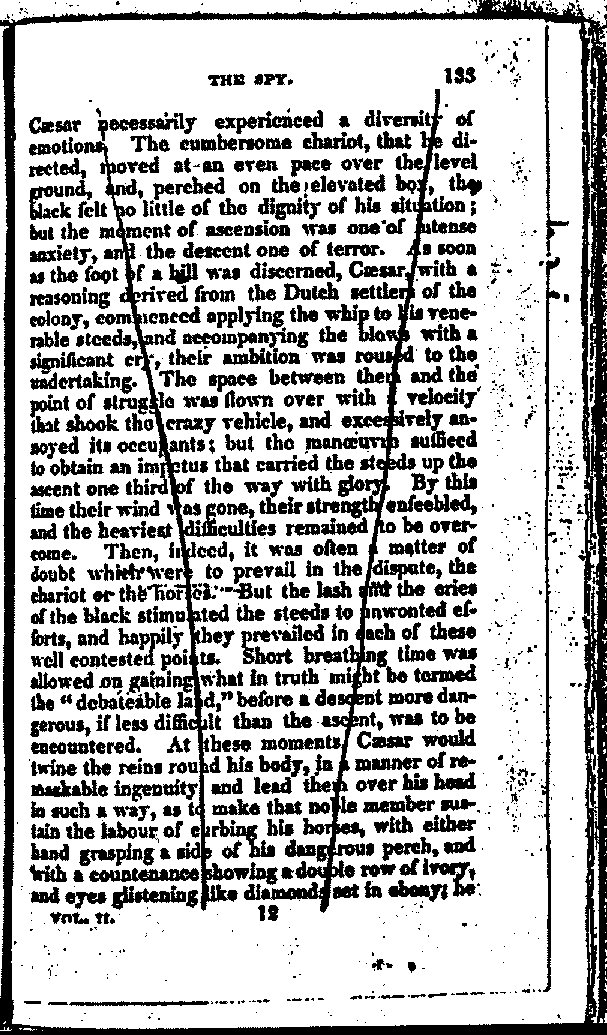

Another example of a major change in The Spy is Cooper’s wrestling with the opening of chapter 9 in the second volume, Illustrations 5-8 In the description of the West Chester landscape — very familiar to Cooper through the farms owned there by his wife, Susan Delancy — Cooper set out initially in his revision on the left to shorten and simplify a text which in the original is convoluted, both verbally and politically. In the first edition, Cooper was not able to escape his often-present desire to expatiate upon the political implications of his fiction. Amusingly, ten years later Cooper was no more successful initially in getting his politics and his roads separated. As his revised text expanded, so did his political overtones; Cooper ultimately had to slash both the first text and the revision and force himself finally to write a simple tenline pair of sentences that keep to the topographical facts of “The roads of West-Chester” ( Illustration 8).

Among all these 1831 changes probably the most interesting is the sharper characterization of the main characters. In Illustration 9, for example, the comic scene of the surgeon Dr. Sitgreaves — always willing to display his medico-scientific knowledge — was sharpened by Cooper’s substituting his comic dissertation on the linkage between a wedding ring and the heart for a flatter description. Illustration 10 shows Cooper inventing a lengthy new speech for Sitgreaves in which he rebuts the comments of an English officer concerning the inconsistencies of Americans striving for freedom from England while preserving slavery. Sitgreaves responds with several arguments stock in trade to defenders of slavery: England has no land suitable for large-scale agriculture; England contrives to maintain a pool of paupers as cheap factory labor; the English never criticized the American colonies for enslaving Africans — a trade in which they had themselves profited — until the rebellion, and so on. (Perhaps here Cooper was remembering his own sharp condemnation of slavery in his thinly-disguised political treatise of 1828, Notions of the Americans.)

Finally, Cooper worked hard in his revisions to reshape his women characters. In The Spy, there are five principal women characters: two lower class comic figures, Betty Flanagan and Katy Haynes, and three young women of marriageable age from genteel classes (the sisters Frances and Sarah Wharton, and Isabella Singleton). Cooper introduces Betty Flanagan, an Irish immigrant washerwoman following the revolutionary troops through Washington’s campaign north of New York City, at the beginning of chapter 16. Mrs. Flanagan, whose husband has been killed fighting for the rebel cause, is now serving as sutler to a corps of Virginian troops. First introduced as a “bitch doctor to the troops,” Cooper revised her title — no doubt with an eye towards the gentility of his British audience — in 1831 to “petticoat doctor.”

Illustration 11 shows a typical change in the registration of Betty Flanagan, as she thinks about the campaign she is mounting on her prospective next husband, Sergeant Hollister. In this text, Cooper changed the passage “the washerwoman had for a long time looked on the veteran with the eyes of affection, and had secretly determined within herself to remove the dangers from a lone woman, by making the sergeant the successor of her late husband.” In the 1831 revision, Cooper muted the clear self-aggrandizement of Betty’s speech, and shifted the prose to a more humorous level by changing the second part of the sentence to “she had determined within herself to remove certain delicate objections which had long embarrassed her peculiar situation, as respected the corps, by making the sergeant the successor of her late husband.”

Similarly Cooper enhanced in the 1831 revision the facetious tone characterizing Katy Haynes, who like Betty, is a woman in search of a husband. Katy has set her sights on the eponymous hero of The Spy, Harvey Birch, for whom she serves as housekeeper with the aspiration of eventually becoming his wife. Of gravest concern to Katy is the preservation of Harvey’s fortune made from his trade of peddling. Frequently in the novel Katy laments the possibility of Harvey’s loss of fortune, and for her of course, loss of the principal reason for entering into matrimony with him. But in this passage (Illustration 12) at the bottom of the page, Cooper mutes the open selfishness of Katy by changing the sentence, “Harvey will be nothing but a despiseable, poverty- stricken wretch. I wonder who he thinks would marry him now” to “Harvey will be nothing but an utterly despiseable, poverty- stricken wretch. I wonder who he thinks would be even his housekeeper!”

{91} Finally, in making his revision of the women characters in the 1831 text of The Spy, Cooper took considerable pains to alter the registration of the descriptions for the three genteel young ladies, Frances and Sarah Wharton and Isabella Singleton. Throughout all his revisions to Spy he consistently removed references to the three young women as “maidens,” substituting other phrases such as “girls,” “young women,” or their given names. The intent here seems to reduce the silver-spoon image of “maiden” and to reserve it only for an appropriate context.

Several passages show Cooper similarly reducing the ornate language associated with Frances Wharton in the first edition. In Illustration 13, for example, in two places a reference to her as “the maid” is altered simply to the appropriate pronoun. Note the passage at the bottom of the page where Cooper’s first edition “but the maid, motioning with her hand for silence, continued, in a voice that trembled with her emotions” becomes more simply “but motioning for silence, she continued, in a voice that trembled with her fears.” Similarly, the description of the very heightened sensibility of Sarah Wharton, caused by Harvey Birch’s dashing her hopes for wedlock with the perfidious colonel, is simplified in Illustration 14 where Cooper simply deletes several charged interchanges between the three young ladies, Isabella, Frances, and Sarah.

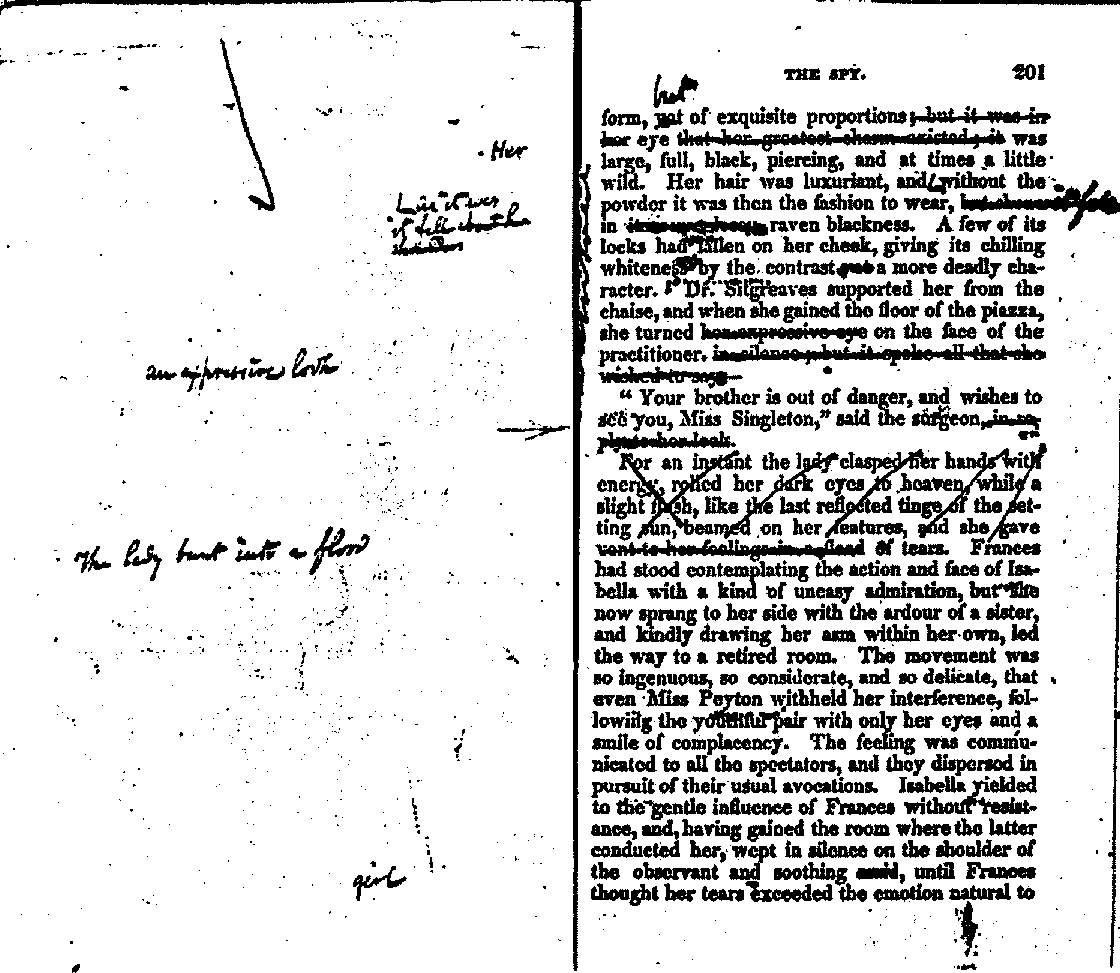

Finally, Isabella Singleton, a hot-blooded southern belle introduced into the novel as a potential competing love interest for the hero, Payton Dunwoodie, serves throughout to heighten the suspense about the Dunwoodie-Frances romance. Cooper often deleted or diminished Isabella’s theatrics, as in Illustration 15, where “The lady burst into a flood of tears” replaces 5 lines of “clasping,” “rolling,” “beaming” and “flushing.” Cooper conveniently removed Isabella from the scene by embedding a stray bullet from a guerrilla warrior in her bosom. In a passage that illustrates the occasional fun of being a textual editor, Cooper provided the only example I know of in any of his extant revisions in which he records an authorial emotion clearly private and not intended for the public. On Illustration 16, on the page where Isabella dies, Cooper wrote in parentheses, “I’m damned glad she is dead.”

In conclusion, Cooper’s revisions for The Spy, illustrated here from emendations he made himself based on the evidence of his extant manuscript changes, were significant and extensive. As a professional author more experienced both with writing and with publishers, in 1831 Cooper pruned the excessive verbiage of Spy, sharpened character and dialect, moved action and dialogue along more swiftly, and sometimes enhanced his comic dialogue. Cooper had complained bitterly to Richard Bentley that the publisher had allowed him too little time to perfect The Spy: “Had you given me more time, I could have made a good book of the Spy, but it would require material changes, in the text, and some in the story.” But he added promptly, and with good reasons as these examples of his revisions show, “As it is, I think it very materially improved.” 3

Notes

1 Cooper to Andrew Thompson Goodrich, publisher of Precaution, 25 April 1820, in The Letters and Journals of James Fenimore Cooper (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1960-68), 1, 54-55.

2 Ibid., 1, 44.

3 Ibid., 2, 67-68.

Illustrations

The following 16 illustrations, showing holographic revisions made by Cooper to the original edition of The Spy, were shown as slides during the original presentation of this paper. They are reproduced through the courtesy of and with the express permission of the Berg Collection of English and American Literature, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, which owns the original documents:

Illustration 1.

Illustration 2.

Illustration 3.

lIlustration 4.

Illustration 5.

Illustration 6.

Illustration 7.

Illustration 8.

Illustration 9.

Illustration 10.

Illustration 11.

Illustration 12.

Illustration 13.

Illustration 14.

Illustration 15.

Illustration 16.