Moravian Origins of J. F. Cooper’s Indians

James Fenimore Cooper Society Miscellaneous Papers No. 22, February 2006.

Copyright © 2007.

[May be reproduced for instructional use by individuals or institutions; commercial use prohibited.]

“A View from Moravia”

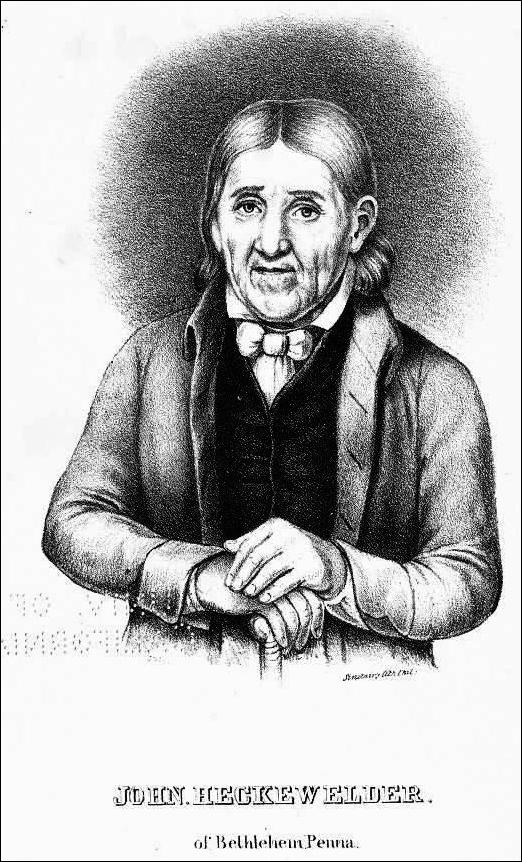

Much has been written about the influence on Cooper of John Heckewelder, the Missionary of the Moravian Church whose writings about the Delaware and Mohican Indians so strongly influenced Cooper’s vision of Native Americans. This paper by Professor Michal Peprnik was presented at the 11ᵗʰ American Studies Colloquium, on the theme “America — Home of the Brave,” held at Palacký University in Olomouc, in the heart of Czech Moravia, on August 29-September 3, 2004. When we heard about it, we hastened to ask Professor Peprnik for permission to publish it in the Cooper Society Miscellaneous Papers series. In due course it will be added to our website.

In addition to demonstrating the strength of Cooper scholarship today in Central Europe, Professor Peprnik’s paper provides what might be called a Moravian view of Cooper’s Moravians, and we thank him for letting us make it available to the members of the Cooper Society.

The American Studies Colloquium, held annually at Palacký University, includes an extensive range of papers on American literature. In the 2005 Colloquium, on the theme “Cult Fiction, Films, and Happenings,” Professor Peprnik presented a paper on “Our Indian: The Cultural Appropriation of the North American Indian.” We hope that this Colloquium will continue to include papers exploring James Fenimore Cooper and his works and world, and that we will have the privilege of sharing some of them with our members and, through our website, with Cooper scholars everywhere.

— Hugh C. McDougall, Secretary

Introduction

There can be hardly a more preposterous topic than this one. Perhaps only the Moravian origins of Natty Bumppo could compete. Any defense of such an apparently desperate position must undoubtedly be a hopeless enterprise, another lost cause.

But Cooper has some surprises in store for his faithful readers.

“Damme, Deerslayer, if I do not believe you are, at heart, a Moravian, and not a fair-minded, plain-dealing hunter, as you’ve pretended to be!” (The Deerslayer27)

Could it be possible? Cooper’s most famous literary protagonist, this archetypal American hero, a man of pure white Anglo-Saxon stock, a prototype of the man on the margin on the run from the civilization; WAS THIS GREATEST AMERICAN LITERARY MYTHIC HERO A MORAVIAN? In the light of this discovery even the search for the Moravian origins of Cooper’s Indians may appear more plausible.

When Deerslayer alias Natty Bumppo was branded as a Moravian, the point of reference was not the eastern part of the Czech Republic but the Moravian Brethren, a Protestant sect (called often just the “Moravians” in America), who did originally come from Moravia and in the 18ᵗʰ century established missions among the North American woodland Indians. Those mission Indians were often called Moravian Indians.

Cooper’s Moravian Indians

I am pleased to say that J. F. Cooper’s first Indian is a Moravian Indian. He was converted to Christianity by the Moravians (The Pioneers134). He was no minor character; on the contrary, he happened to be Cooper’s most famous Indian character and was cast as a mythological companion of Natty Bumppo. He was known to the settlers as the old Indian John, alias John Mohegan, but his original Indian name was Chingachgook and he was the last member of a distinguished Mohegan family. He made his first appearance in The Pioneers (1823), the first novel of the Leatherstocking Tales.

His Moravian conversion finds support in history. Some groups of Mohegan Indians joined the missions organized and supported by the Moravian Brethren and they were sometimes called the Moravian Indians.

While we, Czech Moravians, can take Cooper’s choice as a tribute to the cultural influence of Moravia, America has generally been less inclined to pay any tribute to the Moravians. In the quotation above, the statement about Deerslayer being a Moravian is actually an accusation. As if to be a Moravian in America was NOT a very desirable thing. What was desirable is given in the second part of the quotation.

Of course one should take into consideration the context of this accusation and the character of the speaker. This statement was made in The Deerslayer by a rough unscrupulous frontiersman, called Hurry Harry. D.H. Lawrence in his typically scathing manner compared him to “a handsome impetuous meatfly” (p.67). Even though Hurry Harry is far from being a positive and reliable speaker, he is in many other respects a socially representative speaker-he embodies the dominant prejudices of the frontier society that is perceived as the archetypal model of the American society. When he says that to be a Moravian is mean and wrong, it sticks, and we need to explore why.

The Moravians — A Brief History

The Moravian Brethren were a Protestant church that sprang from Unitas Fratrum (1457), Jednota bratrská. It was founded by the followers of a South Bohemian religious reformer, Peter of Chelcice. The Brethren were even more radical than the celebrated reformer John Hus — they advocated non-violence, refused to take oath and accept secular authority, rejected distinctions in rank. They were pushed out of Bohemia and survived for a time in Moravia. Their impressive school system was open to anyone who showed some talent. In their printing house they published hundreds of books, including the most prestigious translation of the Bible from Hebrew and Greek (a Czech equivalent to King James’ Authorized Version). Their last bishop, the world-renowned educator and thinker Comenius, was invited to become the first president of the newly founded Harvard College. Comenius, however, declined the offer. In the end, during the enforced catholization of the Czech lands in the 17ᵗʰ century, the Moravian Brethren had to leave the country. Some of them found refuge at Herrnhut, Saxony, on the estate of Count Zinzendorf, their convert, who in 1727 began to organize the expansion of the Church. He initiated the first mission to the West — he called this ambitious plan the “Brotherly Agreement to Walk According to the Apostolic Rule”. The reorganized Unity of Brethren soon came to be called the Moravian Church in honor of those first Brethren who came to Herrnhut from Moravia. The first mission was set up in the Virgin Islands, on St. Thomas, in 1732. The first Moravian settlement on American mainland was founded at Savannah, Georgia, in 1735. Since the Moravians refused to bear arms, they had to move to Pennsylvania. Their largest Indian mission was established in Gnadehutten between 1746-55, with the Delaware and Mohican population of some 500 people. The Indian settlements were subject to mistreatment on all sides and had to move frequently. The Moravians were reported to be “an evil minded, designing people, disaffected to the government” (Heckewelder 23). The Moravians were suspected of assisting the Indians and the enemy, be it the French, the Jacobites, or the English. Their Indian converts became scapegoats during various riots and campaigns, the greatest tragedy occurring in 1782, when 90 converts from Gnadenhutten, men, women and children, were massacred and scalped by the American militia. This tragedy badly affected further Moravian activities.

The Moravians, like other followers of assimilation, tried to refute the major arguments used against the Indians: that is, that as nomadic people the men were occupied with hunting and war and thus were not fit for work and for cultivation of land (agriculture was the task of women). By converting the Indians to Christianity and emphasizing the spirit of the New Testament and the example of Jesus, especially the notion of brotherly love and forgiveness, they made their converts abstain from personal revenge. On the economic side, the Moravians changed Indian men from hunters and warriors into farmers. Hunting became only a sport and recreation and a complementary activity in winter. Thus they tried to prove that the Indians were adaptable provided they were given a fair chance and fair treatment.

To secure economic success of their mission the Moravians wanted them to be as self-sustained as possible. Even though the Indians could live in large Indian towns, build houses, have fields and gardens, they usually lacked the industrial facilities and in the 18ᵗʰ century became heavily dependent on white products (clothes, blankets, farming tools, kitchen utensils, weapons). The Moravians, however, designed their Christian Indians villages exactly like their white villages-besides a Church and a school, they built facilities such as mills and smithies, they trained mechanics to operate and maintain the machinery, they taught the Indians to make the iron tools by themselves and thus not be dependent on the white traders. A similar pattern of settlement was developed elsewhere, especially among the Southern tribes, such as the Creek Indians, but only much later in the first decades of the 19ᵗʰ century. The Moravians also took a firm stand on the issue of fire-water, the whiskey and rum traders were not allowed to enter their villages, traders were not allowed to serve whiskey during business dealings. During the wars the Moravians remained strictly neutral. Their pacifism was another cause for suspicion and spite among the settlers and local authorities. Their Indian-friendly policy was naturally not welcome by both the white settlers and the white traders. White settlers wanted Indian land and traders wanted to make profit by cheating the Indians and selling rum. So both groups conspired to obstruct the Moravian projects. They needed the Moravian Indians to fail, to drive them from the fields back to the forests.

For a time the Moravian Indians did well. While the Native Indians often starved in winter and especially in early spring because they never kept large stocks of grain, the Moravian Indians, if the political situation allowed it, had food enough to host even large numbers of their hungry relatives. Due to this steady diet and work in the fields they even looked stronger, they were healthier and could have even more children than their wilder relatives. [Note: for detailed accounts of the history of Moravian Brethren in the U.S.A. see Kohnova, Heckewelder, Merritt, Ruttenber 196-207.]

The Moravian projects finally failed. Most of the Indians in the territory did not take part in it, and alcoholism continued to spread. The story of harassment and persecutions and difficulties they had with the local English authorities and with the British settlers who formed the majority among the frontier settlers are a moving and a fascinating addition to the American history as a land of free and home of the brave.

Moravian Indian?

A close examination of John Mohegan, Cooper’s first Indian character, yields a somewhat disheartening result for every true Moravian. Even though converted to Christianity by the Moravians, his fiery Indian nature and his proud spirit could not be subdued. The two systems of thought were obviously at war in his mind. He was instructed by the new pastor of the village (no Moravian) to be humble and meek, to enjoy peace in his heart, but already his appearance and his clothes clearly indicate the uneasy relationship, pride, and smoldering discontent.

From long association with the white-men, the habits of Mohegan, were the mixture of civilized and savage states, though there was certainly a strong preponderance in favor of the latter. ... Notwithstanding the intense cold without, his head was uncovered; but a profusion of long, black hair, concealed his forehead, his crown, an even hung about his cheeks, so as to convey the idea, to one who knew his present and former conditions, that he encouraged his abundance, as a willing veil, to hide the shame of a noble soul, mourning for glory once known. ... The eyes were not large, but their black orbs glittered in the rays of the candles, as he gazed intently down the hall, like two balls of fire.” (The Pioneers 85, the bold type is mine.)

The struggle of the two cultures is finally resolved in the last return of the savage state. John Mohegan dies as Chingachgook. Instead of Christian appeasement and confession, he leaves the world dressed in his Indian clothes and decorated with his chief insignia, chanting a war song, getting ready to enter the eternal hunting grounds and not the pastures of Christian heaven.

Sadly enough, I also have to admit that John Mohegan or Chingachgook was not only the first but also Cooper’s last Moravian Indian. Being left with a single Moravian Indian, Chingachgook, who returned to his old faith anyway, I should probably conclude that this kind of Moravian imprint was only skin deep. I can imagine that a less Moravian-friendly critic might even say that my thesis stands on a single leg, which is a rather shaky support of the body of this work.

Cooper and the Moravian Connection

It is therefore time to introduce the Moravian connection. Cooper’s Moravian connection was John Gottlieb Heckewelder (1743-1823), a missionary of Moravian brethren, whose father came from Moravia. His book History, Manners and Customs of the Indian Nations who Once Inhabited Pennsylvania and the Neighboring States (1819) was published four years before Cooper’s first Indian novel. It was in fact the main source of Cooper’s knowledge of the Indians. Cooper always held Heckewelder in high esteem. He referred to him as: “the pious, the venerable, and the experienced Heckewelder,” and expressed his sorrow that such “a fund of information ... can never again be collected in one individual. He laboured long and ardently in their behalf [of the Indians], and not less to vindicate their fame, than to improve their moral condition.” (Preface to The Last of the Mohicans 472).

John Gottlieb Heckewelder (1743-1823). https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/g-h/heckewelder-john-gottlieb-ernestus-1743-1823/.

Heckewelder’s influence has been noted in Cooper’s criticism but generally downplayed since a missionary has little credit with modern scholars. For instance Paul A.W. Wallace claims that Cooper found in Heckewelder “the philosopher’s stone-a curious view of Indian relations which, in the hands of a romancer, was capable of transmuting base metals of fact into fairy gold.” Wallace argues that Cooper drew inspiration from Heckewelder’s principal error: “an idea that the woods of America were divided between Indians of two sorts, the noble savage and the savage fiend, the former personified, with qualifications, in the Lenni Lenape or Delawares (with all their related Algonquian tribes, including the “Mohicans”); the latter, without qualification, in the “Mingoes” (“Maquas”) or Iroquois, i.e., the Six Nations.” Wallace not only rejects such a schematic division, he in fact stands up in defense of the Iroquois.

Heckewelder’s book should not be dismissed as an emotionally biased account that drew on the Delaware version of history. He checked the received information also outside the Delaware community. His book remains an impressively detailed and complex study of various aspects of the woodland Indian culture, drawing on his own years of experience among the Delaware Indians and being a sort of diplomat for the Moravian Brethren as well as on the experience of other Moravian missionaries.

In fact Wallace’s criticism is unfair in more than one respect. As I have shown in my paper at the 7ᵗʰ Brno conference, Cooper created a greater variety of Indian characters than is generally supposed. The more recent criticism has also objected against the easy black-and-white classification (McWilliams 57, Rans 110). Wallace’s article was written in the Cold War period and he appreciated the pax iroquoia because it created a safety belt for the English colonies. He is less interested in the more complex moral issues that appealed to Cooper and Heckewelder — for instance the imperialist character of the Iroquois politics. The Iroquois sold the Delaware lands, enforced their authority over the neighboring tribes through terror. Interestingly enough, Cooper never uses this fact, as if this fact was too humiliating to be presented and would make the Delaware the subjects of Iroquois domination.

What could Cooper learn about the Indians from Heckewelder? The answer is, practically everything he needed. Interestingly, and significantly, considering the amount of information available in Heckewelder, relatively little enters Cooper’s Indian novels. But this little is a precious little. Since the process of writing is not just a process of representation of reality in the mimetic sense but to some extent an autonomous artistic process based on selection and combination, which is subordinated to the thematic plan and the demands of the plot, we’d better try to understand the rationale behind the absences and presences.

In Heckewelder Cooper found not only the name Uncas for his famous hero but also the name for his first and best-known Indian character, Chingachgook. In The Pioneershe was known among the settlers of Templeton as John Mohegan. Heckewelder speaks of having met Mohican John in 1762. He was a chief of a group of Mohicans in 1762, who went to Ohio (History93).

The question that may strike every Heckewelder reader is why Cooper chose the Mohican as his prime choice in The Last of the Mohicans. Why not the Last of the Delawares if the Delaware were presented by Heckewelder as a far more important tribe than the Mohican?

Cooper followed Heckewelder’s lead and identified the Mohican with the Mahican (Mahicanni), who were considered by Heckewelder as a split-off section of the Pequot Indians. According to modern sources, both Heckewelder and Cooper blended into one two Algonquian tribes of probably common origin, the Mahican and the Mohegan. The Mahican lived in the northern end of the Hudson valley, in southern Vermont and Western Massachussetts. The Mohegan, a faction of the Pequot tribe, lived in Connecticut.

Both choices were convenient for Cooper’s purposes because the Mohegan under the leadership of Uncas and his descendants became faithful allies of the English in the Indian Wars and during the American revolution of the Americans, while the Mahican waged a long though unsuccessful war against the Iroquois in the 17ᵗʰ century (see Wallace, Waldman, Simmons 31-36). From Cooper’s point of view, the Mohican, were “progressive” Indians (someone might prefer to say ‘opportunistic’) because they realized who was the superior power in the region, and therefore chose cooperation rather than resistance as the means of tribal and cultural survival.

Another reason why Cooper chose the Mohicans for the main role because he believed that the Mohican avoided the controversial and eventually humiliating treaty between the Delaware and the Iroquois, which assigned the role of womento the Delaware. This meant they had to lay down weapons and perform the diplomatic role of the peacemakers (Narrative xxvi, 53-66, see also Wallace for a different reading). As a result, the Mohicans could be then regarded as superior because they maintained the warlike spirit and in effect a greater sense of honor. For Cooper war and martial spirit were obviously an integral part of the male culture, be it Indian or white. Practically all his main protagonists, regardless of their social background, have to go through a test by fire, in Richard Slotkin’s famous formulation, the regeneration by violence. The choice of the Mohicans was convenient because it removed the two heroes from the scene of compromise and diplomatic deceit.

Besides these pragmatic reasons, Cooper’s romantic imagination must have been excited by Heckewelder’s opening lines about the Mahicanni, or Mohicans: “This once great and renowned nation has almost entirely disappeared, as well as the numerous tribes who had descended from them.” (93) First, Heckewelder’s reference to a nationthat further subdivides into numerous tribes sounds grandiose as if hundreds of thousands people were alluded to and not just thousands reduced to hundreds. The opening lines also create another romantic contrast between the past glory and the present decline. The sad history of the tribe and its dispossession, maltreatment, extinction through war and disease, and scattering could work well as the trope of the Vanishing Indian.

The Delawares were needed for different purposes and once again Heckewelder provided the material.In spite of his enticing appreciation of the former glory of the Mohican, Heckewelder prefers the Delaware, or Lenni Lenape, as they call themselves, and regards them as the most important Algonquian tribe (on nation) in the region. Their original sphere of power or influence had stretched over a large territory outlined by four rivers, the Delaware, the Hudson, the Susquehanna, and the Potomac.

The most convincing evidence offered by Heckewelder about the importance of the Delaware is the fact that the Delaware were recognized by the surrounding Algonquian tribes as the grandfathernation. As usual in Indian language, this expression can carry literal as well as various symbolic meanings. The frame of family relations was often used not only for the expression of power relations (subordination) but also for acknowledging authority springing either from old age or wisdom. Heckewelder used both ways-the Delaware were the nucleus tribe from which the other tribes separated and to which they were related and whose senior authority they respected. Heckewelder states that nearly forty Indian tribes, in those days called nations, acknowledged the Delaware, or Lenni Lenape (people at the rising of the sun) as their grandfathers (Narrativexli). The claim to their superiority is supported both by evidence from politics and linguistics (a high degree of sophistication of their language, as judged by 19ᵗʰ-century standards). The Mohican, Cooper’s blend of the existing tribes, the Mahican and of the Mohegans (a split-off faction of the Pequot Indians), were seen as closely related to the Delaware. Heckewelder regarded the Mohican as a people of mixed stock, therefore by the Indian and white 18ᵗʰ-century standards, less prestigious (Narrativexl-xli). Cooper was obviously fascinated by the genealogyof the Delawares. As Jane Tompkins put it in her Lévi-Straussian reading, Cooper’s novels are “a meditation on kinds”, that is “how much violation or mixing of its fundamental categories a society can bear” (105). In the American melting pot the immigrants from different national (though European) background looked for a new line of purity. This new line became the color line. The color line could also be enacted in different frames, and the Indian culture was one of them. This celebration of unmixed, pure origin went along with the pre-Romantic interest in myth and heroic ages-the nostalgia for the pre-industrial mythic and pre-modern golden ages.

From the thematic point of view, the most important borrowings from Heckewelder can be found in The Last of the Mohicans. Cooper used a part of the Delaware myth of the coming to their ancestral lands and drew inspiration from Heckewelder’s reference to the original three clans of the Delaware, the Wolf, Turkey and Turtle. It was the image of the turtle that set spurs to his imagination and helped to create one of the most unforgettable scenes in American literature.

Cooper treated the myth of the arrival as a history with political implications. The arrival in their promised land entailed a conquest of the territory and this is used as a justification for the white conquest of America, making the conquest a pattern of history, where the stronger beats the weaker and takes all. The Delaware, and that means also the Mohican, like the whites, also took the land by force, and conquered the original population. On the other hand, Cooper’s cultural relativism, reinforced by his reading of Heckewelder, allows for a different perspective - through Chingachgook Cooper makes it clear that the contemporary conquest was unfair due to the white superiority in numbers and technology. The theme of conquest is linked with the romantic theme of dispossession and loss, the passing of a heroic age. The home of the brave in this light appears as a dark and bloody ground.

But my main interest is in the motif of the turtle.

On the Back of the Turtle

When a 19ᵗʰ-century Czech reviewer wanted to capture the charm of the LOM, he recalled the spectacular magic moment of revelation, when a young Delaware tears apart Uncas’s shirt, and finds, to his utter amazement, a blue tattooed turtle on Uncas’s breast. Everybody is struck dumb. Even the Czech illustrators registered the power of this moment and placed the image on the cover of two major editions of the novel.

Covers — Czech editions of The Last of the Mohicans.

This moment of unexpected discovery is like in a good Aristotelian tragedy connected to a peripety, a reversal of fortunes. At the very moment when Uncas is to be bound at stake and tortured as an anonymous traitor and deserter who fought on the English side, at this very moment he is identified by the turtle as a sort of king in disguise. A king who can now claim his lost kingdom. As a matter of fact, this association constitutes one of the thematic lines which were suggested already at the beginning of the novel by the motto in Chapter One, which invokes the image of kings without kingdom and the notion of a lost kingdom. He who was the last, will become the first.

When the picture of the turtle was revealed, Uncas exclaims: “Men of Lenni Lenape! ... my race upholds the earth! Your feeble tribe stands on my shell!” (The Last of the Mohicans 830).

This is a curious statement and mystifying reference. Which race? Red race? First we have to understand that the word “race” did not have the fixed meaning it has now. Race was frequently seen identical with nation or tribe. This connection is confirmed by Tamenund, the old Delaware prophet, who mentions “the wise race of the Mohicans”. Does it mean then that the turtle was the tribal sign of the Mohicans? Or is it a heraldic sign of Uncas’s ‘aristocratic’ family? Uncas comes from a family of chiefs and thus is an Indian aristocrat, a king without kingdom. But there is a third option looming at the background, our Moravian connection.

The motif of the turtle can be traced back again to Heckewelder. In this sense we can give full credit to Wallace who speaks of Heckewelder’s influence as “the philosopher’s stone — a curious view of Indian relations which, in the hands of a romancer, was capable of transmuting base metals of fact into fairy gold”. In Heckewelder, the Turtle (Unamis) was one of the three original tribes or possibly clans of the Delaware, the one which held the Council Fire. Their language, says Heckewelder, was the most musical and highly polished, and they enjoyed respect for their wisdom.

For no where is the language so much cultivated as in the vicinity of the great national council fire, where the orators have the best opportunity of displaying their talents. Thus the purest and the most elegant dialects of the Lenape language, is that of the Unami or the Turtle tribe.” (Heckewelder, History, Manners 327)

Cooper obviously wants to keep open several options: the aristocratic association with the family, the romantic association with the nation fighting for its survival, and mythological association with the original clan structure of a distant heroic age. The way he treats this situation shows his ability to stratify meanings. Uncas is a Mohican, a Turtle and a king of old. His own introduction as “a son of the Great Unamis” evokes the mythic moment of grand beginnings of things, a theme the conservative side of Cooper found so fascinating. In Uncas the heroic ancestor and founding father seems to be reborn and with him the lost glory is regained. The Delaware, unmanned by its neutrality and the consequent decline, are regenerated with the return of the young king. They cease to be women and peacemakers, and go to war against the Hurons, who are presented by Cooper as their traditional enemy (this is not historically accurate but an explanation of this complicated case is beyond the scope of this paper). The battle with the Hurons has also another level of significance, unnoticed by the critics: the Delaware go to battle with the Hurons not only because they were offended by Magua but also to win back the white bride for Uncas, and thus secure the continuation of the natural cycle.

In the scene of discovery (peripety) Cooper shifted Uncas into the thematic focus. It is a great moment for Uncas, a moment when romance turns into myth. Uncas assumes the role of a cultural hero, whose task is to renew the lost cosmic balance. As Darnell put it in his paper, “he is Alpha and Omega, both prophecy and the fulfillment” (265). Through Uncas the mythic cyclical vision of history is briefly restored, Mohican Uncas enacts the return of the king that will heal the wounds and restore the lost glory and put the Delaware back to position of their power. His return will reverse the linear march of the white history. It is a breathtaking moment of Cooper’s mythopoeic imagination.

Quite understandably, Cooper follows the course of history and the possibility of new starts turns into a tragic ending, the romantic theme of loss. The Indian second start is postponed indefinitely into the uncertain far future.

Even though Uncas is removed from the fiction world, he continues to dominate and structure our imagination by means of the image of the turtle. He is the turtle — a chief, an unspoilt last Mohican, the Vanishing Indian. He carries not only the feeble tribe of the Delaware on his back but as an archetypal Indian also the feeble civilized America. The Home of the Brave should be raised on his back, on his shell. So while in a historical sense Cooper thematized through Uncas the passing of the Indian, in the mythic and cultural sense Cooper immortalized him and showed the importance of the Indian for becoming an American. The Indian has been integrated as a constitutive element of the American character. Heckewelder helped Cooper to find the proper image.

There is another piece of evidence of the importance of Heckewelder and the Moravian enterprise: among the rich gallery of Cooper’s characters no Moravian missionary will be found — there are Quakers, puritans, Methodists and clergymen of other denominations, but no Moravian. This absence is conspicuous and significant. Especially when we become aware of the dialogic character of Cooper’s writing — no one escapes at least a touch of irony — most of his pastors and missionaries are more or less comic characters even though they may occasionally achieve their moments of glory and dignity. It is as if Cooper wanted to spare the Moravians.

For Cooper, even though he became at the end of his life much more religious, Heckewelder was probably not so much interesting as a missionary converting the Indians to the white religion, more likely he saw in him a cultural relativist and Indian apologist. Heckewelder taught Cooper to respect the Indian culture and understand it not only from the outside, the white perspective, but also from inside, from within the culture, with its own inherent rules.

The vision is Cooper’s, the material Moravian, Heckewelder’s. This is the great Moravian contribution to American myth-making imagination.

Cooper’s Indian Novels

The Leatherstocking Tales

- The Pioneers; or, The Sources of the Susquehanna (1823)

- The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 (1826)

- The Prairie: A Tale (1827)

- The Pathfinder; or the Inland Sea (1840)

- The Deerslayer; or, The First War-Path: A Tale (1841)

Littlepage Trilogy

- Satanstoe; or, The Littlepage Manuscripts: A Tale of the Colony (1845).

- The Chainbearer; or, The Littlepage Manuscripts (1845)

- The Redskins; or, Indian and Injin: Being the Conclusion of the Littlepage Manuscripts (1846)

Other Indian Novels

- The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish: A Tale (1829)

- Wyandotté; or, the Hutted Knoll (1843)

- The Oak Openings; or, the Bee-Hunter (1848)

Illustrations

- John Heckewelder

- Burian, Zdenek. Cover picture of Uncas. Poslední Mohykán. By J. F. Cooper. Trans. Fr. Austin. Praha: Jof.R. Vilímek, 1948.

- Vraítil, Jaromír. Cover picture of Uncas. Poslední Mohykán. By J. F. Cooper. Trans. Vladimír Henzl. Praha: SNDK, 1961.

Works Cited

- Cooper, James Fenimore. Introduction to The Last of the Mohicans. Leatherstocking Tales, vol. 1. 1831. New York: Library of America, 1985.

- Cooper, James Fenimore. The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757. 1826. New York: Library of America, 1985.

- Cooper, James Fenimore. The Oak Openings; or, the Bee-Hunter.1848. Project Gutenberg, 2003. Oak Openings

- Cooper, James Fenimore. The Pioneers; or, The Sources of the Susquehanna. 1823. New York: Bantam Books.

- Cooper, James Fenimore. The Redskins; or, Indian and Injin: Being the Conclusion of the Littlepage Manuscripts. 1846. New York: Burgess & Stringer. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library. 1997 Redskins

- Cooper, James Fenimore. Satanstoe; or, The Littlepage Manuscripts: A Tale of the Colony.New York: R. P. Fenno & Company, 1845.

- Cooper, James Fenimore. The Wept of Wish-ton-Wish: A Tale.1829. New York: W. A. Townsend and Company, 1859.

- Cooper, James Fenimore. Wyandotté; or, the Hutted Knoll.Philadephia: Lea & Blanchard, 1843.

- Darnell, Donald. “Uncas as Hero: The Ubi Sunt Formula in the Last of the Mohicans.” American Literature37.3 (Nov. 1965): 259-266. Jstor, 23.2.2005. JSTOR

- Driver, Harold E. Indians of North America. 2ⁿᵈ ed. Chicago and London: U of Chicago Press, 1961, 1969.

- Heckewelder, John Gottlieb. History, Manners, and Customs of the Indian Nations.1819. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1876.

- Heckewelder, John Gottlieb. The Narrative of the Mission of the United Brethren among the Delaware and Mohegan Indians, from its Commencement in the Year 1740, to the Close of the Year 1808. Philadelphia, 1820.

- Kohnova, Marie J. “The Moravians and their Missionaries: a problem in Americanization.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 19. 3 (Dec. 1932): 348-361. Also available at JSTOR

- Lawrence, D. H. Studies in Classic American Literature. 1923. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1977.

- McWilliams, John. The Last of the Mohicans: Civil Savagery and Savage Civility. New York: Twayne’s Publishers, 1993.

- Merritt, Jane T. “Dreaming of the Savior’s Blood: Moravians and the Indian Great Awakening in Pennsylvania.” William and Mary Quarterly3ʳᵈ ser. 54. 4 (Oct. 1997): 723-746. Also available at JSTOR

- Peprník, Jaroslav. Amerika ocima ceské literatury od vzniku USA po rok 2000. Vol.1 [America through the eyes of Czech literature]. Olomouc: UP v Olomouci, 2002.

- Rans, Geoffrey. Cooper’s Leatherstocking Novels. A Secular Reading.Chapel Hill and London: U of North Carolina P, 1991.

- Ruttenber, E. M. Indian Tribes of Hudson’s River 1700-1850. 1872. 2ⁿᵈ ed. Saugerties, N.J.: Hope Farm Press, 1999.

- Simmons, William S. Spirit of the New England Tribes. Indian History and Folklore.Hanover and London: UP of New England, 1986.

- Slotkin, Richard. Regeneration through Violence: the Mythology of the American Frontier 1600-1860.1973. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000.

- Spencer, Robert F. and Jennings, Jesse D., et al. The Native Americans.2ⁿᵈ ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1977.

- Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs: The Cultural Work of American Fiction 1790-1860. 1985. New York and Oxford: Oxford UP, 1986.

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes.Rev. ed. New York: Checkmark Books, 1999.

- Wallace, Paul A.W. “Cooper’s Indians.” New York History35.4 (Oct. 1954): 423-446.